Flooding in downtown Montpelier, Vt., on July 11, 2023. (John Tully for The Washington Post )

With $14 billion in new federal funding, the infrastructure law was supposed to jolt efforts to protect the U.S. highway network from a changing climate and curb carbon emissions that are warming the planet. New records show the effort is off to an unsteady start as hundreds of millions of dollars are being spent elsewhere.

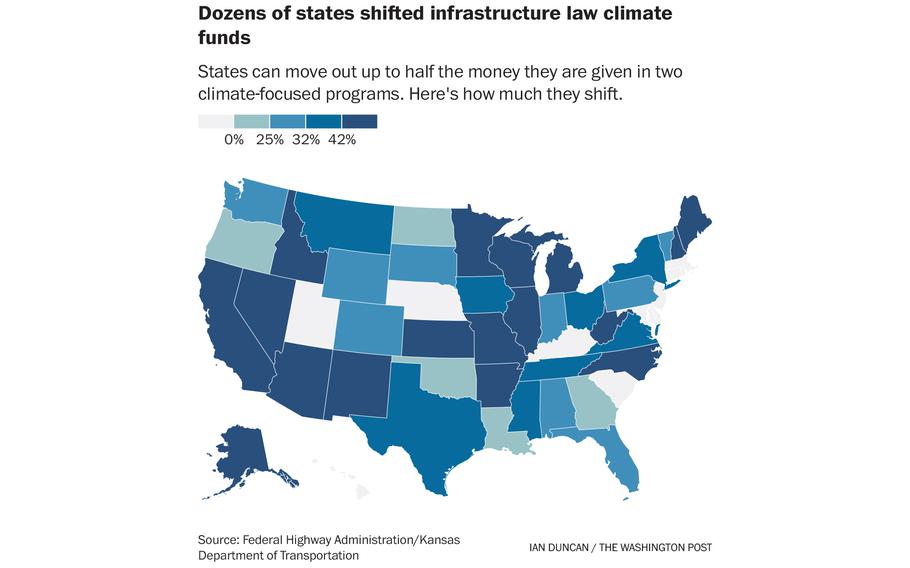

Last year, 38 states made use of a provision in the law to shift about $755 million to general-purpose highway construction accounts, according to Federal Highway Administration records. The sum is more than one-quarter of the total annual amount made available to states in two new climate-related programs.

California shifted $97 million to pay for safety projects. New York moved $36 million to fund what officials called the state's "core capital program." Arizona said it used $20 million for its five-year highway construction program, largely for "pavement preservation," and Louisiana used $8.2 million to fund roundabouts near an outlet mall.

Five states couldn't account for how the money was used after it was transferred.

The nibbling away of climate funding highlights a fundamental tension in the 2021 law, which was crafted to secure bipartisan support. Protections to long-standing flexibility in how states use federal highway funding are hampering efforts by Democrats and the Biden administration to make progress on environmental goals. Amid clashes over federal guidance, the financial transfers from two climate programs - coming as weather events batter the nation's infrastructure with increased intensity - illustrate how states have wide latitude to discount the wishes of leaders in Washington.

The records, released under a Freedom of Information Act request, show several states said they were still putting together plans for how to use the money, typically an injection of tens of millions of dollars annually for each state. Some blamed slow guidance on how to spend the money.

Transportation projects can take years to develop, and many states have only begun grappling with what a changing climate means for their infrastructure and have argued that their power to cut emissions is limited. The overall picture is one of states slowly coming to grips with how to best use a windfall of money intended to shield thousands of miles of roads and bridges and curb carbon emissions.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) credited President Biden's focus on the environment for securing the first-of-its-kind money in the infrastructure law. The agency said it would implement the law as Congress intended, aiming to reduce the role the transportation sector plays in contributing to climate change.

"The Biden Administration recognizes climate change as a crisis facing our nation and has adopted a whole of government response, which has already meant critical new investments in carbon emissions reduction and resiliency in all elements of our nation's infrastructure," FHWA Administrator Shailen Bhatt said in a statement. "These investments are making a difference as states put them to use."

The agency pointed to projects in five states as examples of how funding from the new programs was shoring up the nation's infrastructure for a changing climate. They include raising a two-mile stretch of highway above a flood plain in Kentucky, deepening the foundations of a bridge carrying Interstate 20 in South Carolina and raising the elevation of a highway in Louisiana.

A legal provision predating the infrastructure law allows states to shift up to half of their federal transportation funds among several different programs - a provision that also applies to transportation money from the new law. Kevin DeGood, director of the infrastructure program at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, said Congress clearly intended for money to be allocated to projects that would reduce emissions or protect against extreme weather.

"It's an absolute failure that this is allowed to happen," he said.

Some state transportation departments said the transferred money ultimately will contribute to climate resilience or emissions cuts. California and other states said they planned to transfer money back to the two climate programs in the future - a step that records show Virginia has already done.

In the meantime, federal and state transportation officials are increasingly turning their attention to how a changing climate is putting highways, bridges and rail lines at risk.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg witnessed the consequences earlier this month in Vermont, where a storm dropped as much as 9 inches of rain - about the norm for June and July combined - within 36 hours. The deluge closed almost 300 miles of state roads and affected more than 200 bridges, according to the Vermont Agency of Transportation.

After touring the damage, Buttigieg said punishing weather driven by climate change is increasingly putting infrastructure at risk.

"It feels like every few weeks we see a new flood, storm, heat wave, drought. It's not lost on me that our skies are hazy because of wildfires of a nature and severity that should not be an annual event, and yet, here we are," he said. "Americans are seeing the results of climate change with our own eyes and dealing with the consequences."

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott (R) said the state would use money from the infrastructure law to guard against future disasters.

"By using all these federal resources, we have an opportunity to ensure the infrastructure Vermonters rely on is strong and more resilient," he said.

States can move out up to half the money they are given in two climate-focused programs. Here's how much they shift. (Ian Duncan)

In November, Vermont's transportation agency submitted paperwork to the FHWA to transfer $7 million out of the climate resilience fund to a general purpose transportation building fund, almost the maximum amount allowed by the law. Vermont is among four states that said its transferred funds would still contribute to climate protection projects.

Andrea Wright, the state transportation agency's environmental policy manager, said the agency transferred the money to maximize federal contributions to projects that "meet the intent of the originating funding programs." Most of the money was used to overhaul a section of Interstate 89 that highway officials say was at risk of sinking.

At the same time, Wright said the agency is finalizing resilience and emissions reduction plans, and could transfer money back into the climate programs in the future. Jason Maulucci, a spokesman for Scott, said the state also used federal pandemic relief money to bolster climate resilience.

Officials in Maine, Oregon and Colorado, three other states that transferred money away, also said they might return funds to the climate programs.

"Maine is committed both to maximizing the amount of federal funding under these programs and doing everything we can to prudently and effectively strengthen our infrastructure and mitigate the impacts of climate change," Paul Merrill, spokesman for the Maine Transportation Department, said in an email.

Other states have been quick to put the resilience money to use. Utah repaired flood damage and stabilized a slope. Delaware plans to elevate some its many flood-prone roads.

While most federal transportation funding is allocated to states using formulas - the method of distribution for the new climate and emissions programs - the infrastructure law also included $1.4 billion in new climate resilience grants for Buttigieg to award at his discretion. The FHWA said the agency launched the program this year to let states assess how they might use their formula funds before pursuing the grants.

Jim Tymon, executive director of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, said the criteria for using the resilience funding is strict and states will soon begin to have a pipeline of eligible projects.

"It's hard for any new programs, whether it's states or transit agencies, to be able to ramp up in that first year, especially if guidance and eligibility doesn't come out until later in the fiscal year," he said.

Tackling climate change has been a source of tension between Washington and some states since the infrastructure law passed.

The Biden administration has tried to encourage states to use the money for climate resilience or emission-reduction purposes. Guidance documents for the two programs remind states they are receiving an infusion of funding and to think twice before shifting money around, although many states didn't heed the advice.

After West Virginia became the first state to file paperwork to transfer money from the emissions-reduction program in April 2022, the FHWA's chief financial officer wrote to the state reiterating the guidance. State transportation secretary Jimmy Wriston defended the move during a Senate hearing five months later, saying coordination with federal agencies since the passage of the infrastructure law was "chaotic at best."

"We need the flexibility to do things that will get a result," he said. "By moving that money into a different bucket, you give me the flexibility to take a holistic approach, to look at the overall environmental concerns and put together comprehensive plans to address them."

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., said during the hearing the letter and what appeared to be contrasting guidance to different states "makes no sense, and you wonder, is the right hand talking to the left hand?"

The FHWA said West Virginia received the letter because it was the first to transfer money away from the emissions-focused program, adding that the agency subsequently took a different approach to communicating with states. It declined to describe the new approach.

A spokesman for Capito, her party's leader on the committee that wrote much of the transportation section of the infrastructure law, declined to comment on state fund transfers.

Sen. Thomas R. Carper, D-Del., the committee's chairman, said the dedicated climate funds in the law are "a floor, not a ceiling." He said through a spokesman that "states should incorporate climate resilience into all of their transportation projects, regardless of the funding source."

Beth Osborne, director of advocacy group Transportation for America, said transfers show the infrastructure law did not overhaul how federal transportation funding flows to states, as some in Congress had hoped. Lawmakers instead opted to create programs intended to tackle federal priorities while leaving states free to continue expanding highways, she said.

"Members of Congress and the president asked us to believe that dedicating 2 to 3 percent of the bipartisan infrastructure law's funding to resilience and reducing greenhouse gas emissions was going to do the trick," Osborne said.

Some states transferred money from the climate programs to support spending on transit, a move encouraged by federal officials. Eleven states and the District did not transfer any money last year, according to federal records, and said they would allocate their full amount to resilience and emissions-reduction projects. (Kansas said it transferred its maximum $13 million from the programs, but the transfers were not reflected in federal records released to The Washington Post.)

Some states said they have yet to find ways to spend the new money. In other cases, money that wasn't transferred has been spent on congestion-fighting projects that experts say will have questionable long-term effects on reducing emissions.

South Carolina's transportation department said it used some of the money to redesign interchanges in Charleston and Columbia. Multiple states are investing in technology designed to improve traffic signals and ease vehicle flow.

Such technology can reduce congestion, but researchers have also found that unclogging roads tends to induce people to drive more, spurring more emissions. Alex Bigazzi, a civil engineering professor at the University of British Columbia who has studied the effects of congestion-reducing technology, said it's not the most efficient way to cut emissions.

"It's a stretch to say this is a carbon-reduction strategy," he said. "Traffic volumes are really the major driver of emissions from transportation systems."

The FHWA said the range of projects funded by the program reflects the need for "an all-of-the-above approach" to reducing emissions.

In Rhode Island, some of the resilience money is being used to redesign bridges and roads in Jamestown, on an island off Newport. Pam Cotter, the department's planning director, said the coastal state has been working for years to understand its vulnerability to sea level rise.

The emissions-reduction money in the infrastructure law, she said, will help the state reach a goal of spending $30 million a year on bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

"That's a big investment and a major change than what we've had previously," Cotter said.