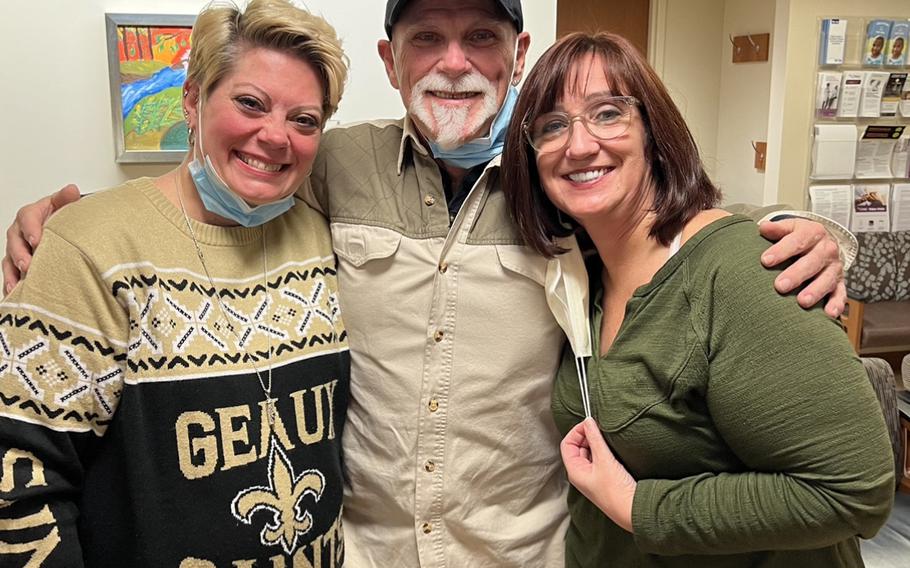

From left, Molly Jones, John Cunningham and Kristi Hadfield. In 2016, Hadfield, a paramedic, saved Cunningham’s life while he was having a heart attack. Six years later, she donated her kidney to Cunningham’s daughter, Molly Jones. (Courtesy Bobby Hadfield)

John Cunningham was driving when he suddenly began to feel strange. He was near one of the county’s emergency medical stations in Ritchie County, W.Va., and decided to stop in, hoping for some medical attention.

There he met paramedic Kristi Hadfield, who he told about his symptoms, including chest pain, and she right away loaded him into an ambulance to head toward the nearest hospital — about 45-minutes away. On the way there that day in 2016, Cunningham, then 65, went into cardiac arrest.

Hadfield immediately began doing chest compressions, and to her relief, his heart started pumping again.

“We were able to get him back,” Hadfield, now 56, said.

At the time, she recalled telling him: “Not today, John. Not today.”

As Cunningham began his full recovery, neither of them could have imagined Hadfield would one day go on to save Cunningham’s daughter’s life, as well.

Shortly after Cunningham’s heart attack, Hadfield found him on Facebook and added him as a friend.

“I like to follow up with my patients to check in and see how they’re doing,” she said.

Before long, Hadfield received a Facebook friend request from Cunningham’s daughter, Molly Jones.

“Of course, I needed to know who saved my dad’s life,” said Jones, 42, who lives in Pennsboro, W.Va.

Over the years, the women stayed in touch on Facebook.

In January of 2022, Jones became acutely ill. It started with bad headaches, swollen feet, chronic fatigue, nausea and later, high blood pressure. She was diagnosed with Stage 4 renal failure, and her kidneys were quickly losing function.

“It was bad,” said Jones, explaining that although as a teen she was diagnosed with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease — an inherited disorder, which causes cysts to develop within your kidneys — she did not anticipate it would progress so quickly and severely.

Her father — a military veteran and retired police officer — moved in with her to help look after her 16-year-old daughter, Viv, who has the same kidney condition.

Molly Jones, in bed, and Kristi Hadfield after the transplant surgery. (Courtesy Bobby Hadfield)

Jones was told she would soon need to start dialysis or get a transplant. On average, patients wait three to five years for a deceased donor kidney from the national transplant waiting list. About 13 people die every day waiting for a kidney transplant.

She decided to post on Facebook about her situation.

“I’ve always used social media as a way to promote organ donation,” said Jones, adding that her mother also had polycystic kidney disease, and had a donor kidney that lasted 18 years. She died a month before Cunningham’s heart attack in 2016.

When Hadfield saw Jones’s Facebook post detailing her health crisis, she reached out with one question: “What blood type are you?”

She learned they are both A positive.

“I have your kidney,” Hadfield told Jones, who was floored by the offer from someone whom she had never met and barely knew.

“I honestly don’t know how long I sat there in shock,” Jones said.

For Hadfield, it was an intuitive response, she said, and she meant it sincerely.

“It was never a thought,” she said. “Molly lost her mom, and I was so glad she didn’t lose her dad, and I knew Molly had a daughter. I wanted Molly to be able to see her daughter grow up.”

Hadfield — who lives in Belpre, Ohio — called the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), to inquire whether she would be a good candidate for a living donor transplant.

“I also discussed it with my kids and my husband and my grandkids,” said Hadfield, who has two children and five grandchildren. Although they were concerned about how the operation might impact Hadfield’s health, “they have been totally supportive the whole time,” she said.

Once Jones was placed on the transplant list in June 2022, Hadfield began rigorous tests to ensure she was a viable donor, including a medical history review, a physical examination, various lab tests and a psychological evaluation — among other hurdles.

“They wanted to make sure that from head to toe, I was perfectly fine,” she said, noting that Jones’s insurance covered all costs associated with the testing and procedure. “They didn’t want to put me in jeopardy, and they didn’t want to give Molly a bad kidney.”

While Hadfield was being tested, Jones’s health was increasingly fragile. She has a blood clotting disorder, which prevented her from doing traditional hemodialysis. Instead, she tried peritoneal dialysis, and it proved ineffective for her.

“I couldn’t get food down. I couldn’t keep food down,” said Jones. “I was fading out.”

Through it all, Hadfield checked in with Jones every day.

“How’s my girl?” she would often ask via text message. “Don’t you quit fighting on me. We’re going to do this.”

Hadfield was determined to have the transplant done before the end of the year. They scheduled the surgery for Dec. 27, 2022, at UPMC.

When the two women met for the first time face-to-face at the hospital on Dec. 19, about a week ahead of the transplant, “tears flowed,” Hadfield said, adding that John Cunningham - now 72 and in good health - was there supporting his daughter.

“It was just amazing getting to see them and hug them,” she said.

It was also emotional for Jones. Up until then, she said, she had a hard time believing the transplant was actually going to happen.

“You hope for the best but expect the worst when you’re that sick,” said Jones.

Amit Tevar, the surgical director of the kidney and pancreas transplant program at UPMC, performed the transplant surgeries, and said he was deeply moved by the background story of the recipient and donor - which was chronicled in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“This really highlights the most altruistic display of humans being humans,” Tevar said. As a transplant surgeon, “I get to see the best of human nature, but this is above and beyond what we normally see.”

Molly Jones, left, and Kristi Hadfield meeting for the first time on Dec. 19, 2022, one week ahead of the transplant surgery. (Courtesy Bobby Hadfield)

Tevar explained the benefits of using a kidney from a living donor versus a deceased donor.

“A living donation is by far a better transplant because it’s done from a healthy donor at an elective time, and they last longer and work better,” he said, adding that there is a lack of information and awareness about becoming a living donor, and it can be difficult to find willing candidates.

“The most important thing for us and for the donor and the recipient is making sure it’s a safe operation for the donor,” Tevar said, explaining that the testing and evaluation process for donors is very stringent for safety reasons.

Although the transplant is not a cure for Jones’s polycystic kidney disease, “it does keep her off dialysis and it extends the length of her life,” said Tevar, explaining that “without this transplant, Molly didn’t have much of a functional life or a length of life.”

Following her operation, Hadfield recovered for three weeks before going back to work as an ambulatory education coordinator.

“I feel great, I have no side effects from this,” she said. “I would not know that I ever had this done if I didn’t, every once in a while, see my scars.”

“The only thing I regret is that I did not do it sooner for her,” Hadfield added.

Jones, meanwhile, has a fully functioning kidney — which she refers to as “the bean” — and is feeling far better than she did when she first entered the operating room.

“My daughter is my entire life, and because of Kristi, I’m going to get to see my daughter graduate, I’m going to get to see her go to college, I’m going to get to see who she grows up to be,” said Jones. “I don’t know how you properly thank someone for that.”

“It is a second chance at life,” said Jones, who works in insurance. “You have to take care of it. You can’t waste your second chance.”

The two women talk every day, and they consider each other - and their extended families - bonded for life.

“I’m just blown away that I was able to do this for them,” said Hadfield. “The neat thing is, I get to watch them live the rest of their lives now.”

She and Jones are planning a party for the first anniversary of the transplant. Jones said the day will be dedicated to celebrating Hadfield.

“I have my dad because of her, and now I have my life because of her,” she said. “I love Kristi Hadfield beyond measure. There are not enough thanks in the world for her.”

Hadfield said she has already gotten more than she has given.

“I might have given a kidney, but my heart grew,” she said. “The blessing that you get from it is so much more than you give.”