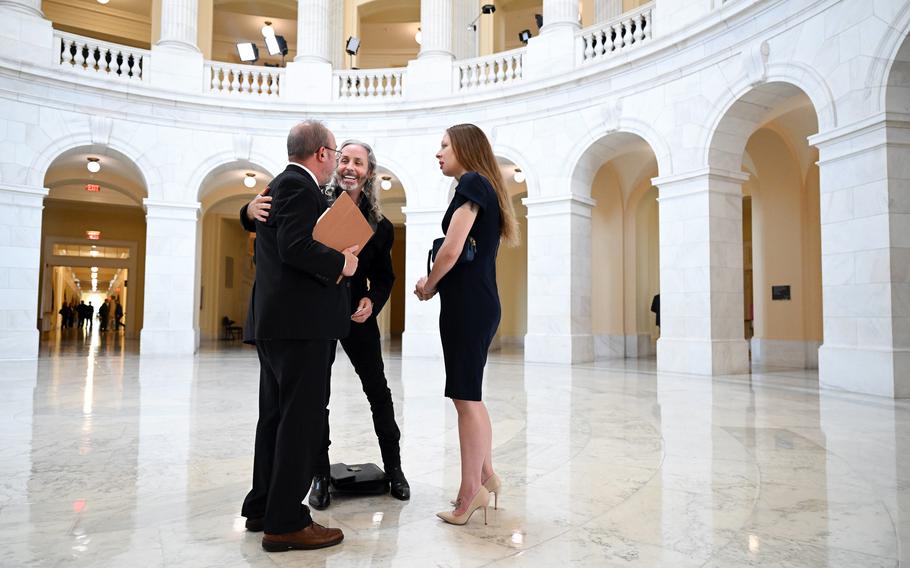

Pro-psychedelics lobbyist Tom Rodgers, center, meets with Rep. J. Luis Correa, D-Calif., left, and policy advocate Amy Rising, right. The National Defense Authorization Act contains language directing Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to conduct a clinical study in military treatment facilities using psychedelics. (Matt McClain/Washington Post)

WASHINGTON — The first time Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced legislation on psychedelic drugs, her proposal came with an unwanted side effect: It gave her colleagues a case of the giggles.

“It was on the House floor,” Ocasio-Cortez said in recent interview in her Capitol Hill office, “and a member of my own party, a senior member, walked up to me and said, ‘Oh, is this your little ‘shrooms bill?’”

The senior Democrat laughed in her face, she recalled, “literally mocking it.” Then, the amendment — which was attached to a large-scale spending bill — failed by a 331-91 vote.

It was a frustrating experience for the congresswoman, then only six months into the job. It was 2019, not 1969, and there was evidence that drugs such as psilocybin and MDMA might offer therapeutic benefits to those suffering from depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction.

And although Ocasio-Cortez was not opposed to legalizing such drugs to some degree, her bill was not even about that. It was simply about removing federal barriers that scientists said made it harder to study the therapeutic effects of psychedelics — namely, by ending a long-standing federal policy prohibiting the government from spending public money on “any activity that promotes the legalization” of certain drugs.

Four years later, the idea is not seen as quite so funny. The shift in attitudes about psychedelics on Capitol Hill since Ocasio-Cortez first introduced her “little ‘shrooms bill” is, in a way, reflective of the New York Democrat’s experience in Congress. It is a parable of shifting perceptions, and the story of how things ultimately get taken seriously in Washington.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., has pushed to remove federal barriers that scientists said made it harder to study the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. (Bill O’Leary/Washington Post)

Within days of that first vote, Ocasio-Cortez said her colleagues were bombarded with calls from constituents, including military veterans and victims of sexual abuse, in support of the legislation. Soon, she said, the same members who were laughing about the bill were apologizing to her for not fully understanding it.

The next time Ocasio-Cortez offered a psychedelics amendment, in 2021, the number of people who voted for it jumped from 91 to 140. Last year, she and Rep. Dan Crenshaw, R-Texas, both passed House amendments on studying psychedelics, but neither measure made it out of the Senate.

There are not a lot of political issues that Crenshaw, the conservative former Navy SEAL, and Ocasio-Cortez, the democratic-socialist former bartender, agree on, but psychedelics is a rare topic that fires up grass-roots activists and big-money investors. Steve Cohen, the hedge-fund billionaire and owner of the New York Mets, recently donated $5 million — part of a $60 million pledge — to help mind-altering therapies go mainstream.

Outside of Washington, the usage of some of these drugs barely registers as counterculture anymore. “Thousands of moms are microdosing with mushrooms to ease the stress of parenting,” read a 2022 headline from NPR.

There are unofficial spokespeople for psychedelics in all corners of popular culture. Sports: “I found a deeper self-love,” NFL quarterback Aaron Rodgers said about his experience with ayahuasca. British royalty: Prince Harry called psychedelics a fundamental part of his life. Tech: “Magic Mushrooms. LSD. Ketamine. The Drugs that Power Silicon Valley,” read a Wall Street Journal headline last month.

And, slowly but surely, Capitol Hill: “Plant medicines like psilocybin and ayahuasca ... they are beautiful because they give you exactly what you need, even if you don’t know what it is you need,” Veronica Duron, chief of staff for Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., said in an interview last year.

Duron, a user of plant medicines, added that she did not know whether her boss would ever personally partake but knows the senator often “hears from his wealthy friends and supporters who micro-dose every day and have these experiences. And he is like, ‘These healing experiences shouldn’t be just for rich White people.’”

Booker has co-sponsored legislation with Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., similar to Ocasio-Cortez’s amendment to study the medical benefits of certain psychedelics. That bill was never taken up last year, but it has been tweaked and reintroduced in the current Congress.

And yet, for all this agreement, it has so far proved difficult to pass any bills related to psychedelics. This is not — according to both Crenshaw’s and Ocasio-Cortez’s offices — because of some organized anti-psychedelics lobbying or big money lining up in opposition. The psychedelics coalition is up against an even more common impediment to change: Washington’s fear of something new.

Some politicians can not help but tune out when it comes to drugs that have long been considered illicit in American law and culture. In 2019, during his run for president, Joe Biden reiterated a long-held belief that marijuana may be a “gateway drug” and that he was not ready to legalize it.

“I am concerned about the president,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “I believe the president has displayed a regressiveness for cannabis policy. And if there’s a regressiveness toward cannabis policy, it’s likely to be worse on anything else.”

Some caveats to that: Last year, Biden announced that he would offer pardons for anyone convicted of a federal crime for simply possessing marijuana; and last week, Biden’s brother Frank said in an interview on SiriusXM radio that the president was “very open-minded” to the idea of medical psychedelics. Contacted for this story, the White House did not comment on the record.

Supporters of psychedelic drug legislation are banking on the fact that these drugs have proved to have a specific mind-bending quality to them, namely that they offer something for all sorts of constituencies. The coalition working on chipping away at the issue in Congress includes not just improbable allies such as Ocasio-Cortez and Crenshaw but also an eclectic group of activists and lobbyists, veterans and survivors of assault, tech bros and spiritualists, who travel to the Hill in hopes of opening minds.

People such as Tom “One Who Rides His Horse East” Rodgers.

— — —

“Most of the people we will be meeting with are supportive. The question is just about whether they want to be vocally supportive.”

He was dressed all in black — an homage to Johnny Cash.

“I grew up listening to him as a young boy,” said Rodgers, who grew up in rural Montana. “And his ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ song came to symbolize for me the need to remember those who have suffered.”

Rodgers, a 62-year-old with a shoulder-length gray mane who has been known to burst into tears describing the beauty of the Milky Way, does not look like a Washington insider at first glance. In fact, he has been a lobbyist for decades, having gotten his start working for former senator Max Baucus, D-Mont., in the late 1980s and eventually making a living working on issues including water and voting rights, opioid legislation and human trafficking.

In 2002, Rodgers acted as a whistleblower to help bring down Jack Abramoff, the corrupt lobbyist who had bilked millions of dollars from Native tribes. This year, Politico named him one of the 40 power players who have shaped culture, race and politics, in part for his work protecting medical marijuana programs for tribes.

Unlike many guns-for-hire in the lobbying world, Rodgers has a spiritual connection to his job. His Native name, One Who Rides His Horse East, refers to the land of “marble dust,” where he had spent decades fighting for Native rights. He received the name during a ceremony last summer at a Blackfeet reservation near Glacier National Park in Montana.

“My job, my vision, is to be a warrior for my people, but not a warrior of 150 years ago out on the Great Plains,” Rodgers said. “Our battles now lie here in Washington, D.C.”

“Most of the people we will be meeting with are supportive. The question is just about whether they want to be vocally supportive,” Tom Rodgers said during a recent visit to the Hill to advocate for relaxing federal restrictions on psychedelic drugs. (Matt McClain/Washington Post)

Rodgers said he is working pro bono on psychedelics legalization, a topic important to many tribes for spiritual ceremonies, and also because of the possibility of using them to treat widespread mental health issues that affect Indigenous people at disproportionately high rates.

The battles over psychedelics policy are being fought in a lot of different places, by a lot of different people, and not always in a centrally coordinated way. There are lobbyists making handsome fees on the issue, and higher-profile advocates speaking in front of congressional panels. Rodgers, for his part, has the ears of many of the key supporters of legislation and plays a role in helping build out that coalition.

Rodgers recognizes the focus needs to be just on healing and not on recreation. Too big a dose of legislation could risk an adverse reaction from low-tolerance lawmakers.

On this mid-May morning, he sat in the office of a congressman who needed no convincing that the drugs deserved serious reconsideration: Rep. Jack Bergman, R-Mich., a co-chair of the congressional Psychedelics Advancing Therapies Caucus. A white-haired retired three-star Marine Corps general, Bergman has spent years looking for ways to improve mental health services for veterans. After losing a nephew — himself a veteran — to suicide in 2001, he says he was forced to ask himself, “How do we do better?”

“Psychedelics had a really bad rap with Timothy Leary and, ‘Turn on, tune in and drop out,’ or whatever the hell that phrase was,” Bergman said. “But I believe there is a place and a need for better therapies and better therapists in our world.”

Later, Rodgers met with Rep. J. Luis Correa, D-Calif., the caucus’s other co-chair, who took a break from a Judiciary Committee hearing to share his thoughts — political and personal — about psychedelic drugs.

“I don’t partake,” Correa said. “I like vodka martinis. That’s what works for moi.”

Correa said he used to smoke cannabis in junior high, often while watching “Reefer Madness” on VHS with his friends for a laugh. Then he became vocally anti-drug as he got older and saw the “destruction” that drugs and alcohol could cause.

The congressman grew up in “an alcoholic family” and saw firsthand “how messed up” that environment could be. He also saw drugs such as heroin devastate the lives of Vietnam War veterans.

“You grow up with this stuff, and it calibrates your mind to be in a certain mind-set,” Correa said.

It ended up being the veterans community that helped Correa change that mindset. After getting elected to the California Senate in 2006, Correa went on to chair the veterans affairs committee, and he kept hearing from current and former members of the military who were having a difficult time getting medical marijuana.

“That sent me on a quest to figure out how to get veterans their medication,” Correa said. “I did a complete 180 on this issue.”

If Correa could change his mind about the issue, he said, anyone could. They just needed to be persuaded by the right people.

— — —

Three years ago, Crenshaw, the Texas Republican, had not even heard about psychedelic treatments for mental health issues. Then, suddenly, it felt as if he could not avoid the topic. It began one evening when the congressman was visiting a friend for dinner.

“Are we drinking beer or wine?” Crenshaw asked him.

“I don’t really drink anymore,” he remembers the friend saying, which took Crenshaw by surprise.

The friend explained that he recently did a regimen of ibogaine, a plant-based psychoactive substance. Years after his armored vehicle was hit by an improvised explosive device in Afghanistan, causing severe brain trauma and possible post-traumatic stress, he had sought relief at an experimental psychedelic treatment facility in Mexico, according to Crenshaw, where the medical staff there administered him the drug over 12 hours. He said he had not had the desire to drink since.

After leaving that dinner, Crenshaw returned to his apartment in the Navy Yard neighborhood of Washington. In the elevator, another man recognized him, thanked him for his work in Congress and pulled up his sleeve to show Crenshaw scars up and down his arm.

“’I’m a Marine,’ ” Crenshaw recalled him saying. “ ‘I tried to kill myself four times.’ ”

Nothing seemed to help, the man said, until he got himself into a psychedelics treatment program with MDMA. Now, this man, a lobbyist named Jonathan Lubecky, was an advocate for psychedelic medicine.

“We should talk,” Lubecky said.

“I was like, ‘Holy s---, twice in one night?’ ” Crenshaw said. “Something I’ve never heard about before? Well, that’s a sign.”

Rep. Dan Crenshaw, R-Texas, speaks during a Republican veterans roundtable in 2021. The former Navy SEAL has come to see psychedelic treatments as “chemo for your brain.” (Jabin Botsford/Washington Post)

The more Crenshaw looked into the issue, the more signs appeared. He started hearing from friends who either had positive experiences with psychedelics or had the desire to try them. He heard from frustrated members of the military who could drink themselves silly and be prescribed all sorts of pharmaceuticals but could not even take CBD, let alone ibogaine or MDMA.

With nearly 17 veterans dying by suicide each day, according to Veterans Affairs, and with some clinical trials showing promise that psychedelics could offer a meaningful reduction in symptoms of PTSD, Crenshaw decided he would do his part to help change the perception on the drugs.

“I’m not even on the marijuana recreational bandwagon,” Crenshaw said, but he has come to see psychedelic treatments as “chemo for your brain. For your demons.”

In 2019, when Ocasio-Cortez first offered her psychedelics amendment, she knew that passage would probably require bipartisan support. So, before offering her “little ‘shrooms bill,” she sought out a Republican to co-sponsor it with her. The best she could do was Donald Trump-loving Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., but he turned out to be better at getting himself booked on television than whipping votes among the drug-resistant strain of conservatives. Only seven Republicans cast their vote in favor of the amendment.

Crenshaw said he recently discussed the legislation with Gaetz, who had suggested that the issue could use support from a member of Congress who was seen as more mainstream. “He was like, ‘I needed you to do this,’” Crenshaw said. “’Otherwise it’s just typical Gaetz, typical AOC.’”

Gaetz, for his part, said he remembers huddling with Crenshaw and Ocasio-Cortez on the House floor this year during the numerous votes to elect a House speaker. He said they discussed the need for a “four corners” approach that included hard-liners from each party as bill sponsors in addition to representatives from the center-right and center-left. He also said the “gerontocracy” of older lawmakers in Congress was partly to blame for the slowness of psychedelic drug legislation.

Gaetz, Crenshaw and Ocasio-Cortez have differing ideologies, to say the least, but they do share at least one thing in common: “Not collecting Social Security,” Gaetz said.

On June 14, Crenshaw announced legislation that would direct Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to provide grants for further research into the use of psychedelics to treat PTSD and traumatic brain injuries for active-duty service members. The bill has seven Republican and five Democratic co-sponsors, including Ocasio-Cortez.

Last week, the coalition received news that it was poised for a bipartisan win in the Republican-controlled House. Thanks to the efforts of Crenshaw and others, the text of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act — the must-pass legislation that includes the annual budget of the Defense Department — included language directing Austin to conduct a clinical study in military treatment facilities using psychedelics. The language is a diluted version of Crenshaw’s bill, but the fact that it is in the text of the bill and is not an amendment makes it more likely to become law.

“Anything that advances empirical research and healing, we are totally supportive of,” Rodgers said. “In America, usually, the only way to make change is incremental change.”

The legislation does not legalize psychedelics or even make them readily available as medicines. It just makes the drugs a little easier to study, and easier to understand. That is often how views soften and moods change in Washington: one micro-dose at a time, until suddenly, everything looks different.