U.S.

Titan's experimental design drew concern even before its doomed dive

The Washington Post June 24, 2023

()

The catastrophic implosion that killed all five people aboard a submersible vessel is likely to intensify calls for stronger regulations and oversight of an industry that has long operated in a legal gray area, experts say.

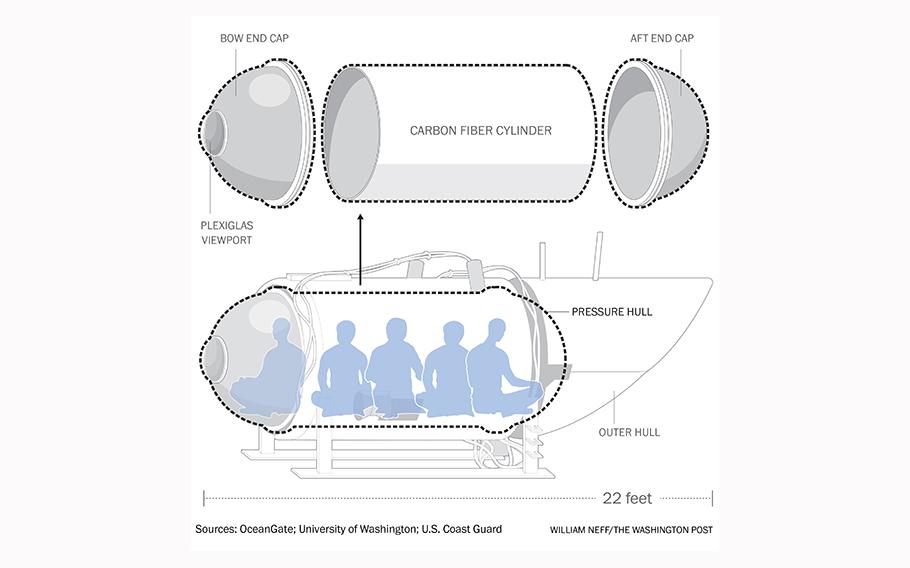

The now-deceased CEO of OceanGate Inc., which operated the Titan submersible for tours of the Titanic wreckage, had hailed the lighter carbon fiber composite hull of the vessel as an innovation in a field in which others have long relied on more expensive titanium models.

But maritime regulation experts and experienced mariners say the material and shape of the vessel gave them concern. They also said OceanGate shouldn't have eschewed the typical inspection process by independent agencies, which is not legally mandated but routinely followed by others in the submersible community. Past lawsuits also raised questions about OceanGate's safety standards.

Rear Adm. John Mauger, who led the Coast Guard's search for Titan, said Thursday that the tragedy is likely to lead to a review on regulations and standards. "Right now, we're focused on documenting the scene," he said.

The company's missions fell outside any single country's jurisdiction, said Salvatore Mercogliano, a maritime historian with Campbell University. The American-made Titan was diving into international waters after launching from the Canadian-flagged vessel Polar Prince. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada said Friday that it had dispatched a team to investigate the Canadian ship's involvement.

"There's literally no requirement out there, because there's no one out there to enforce that," Mercogliano said.

He said at least Canada and the United States are likely to adopt more regulations around submersibles and suggested that the International Maritime Organization - the United Nations' shipping policy arm - may require submersibles to register like other vessels. Right now, he said, they are treated like cargo that is brought aboard a larger vessel coming into port.

Experts say it increasingly looks like the Titan submersible imploded under the pressure of 2.5 miles of ocean water, though an official investigation is ongoing.

Within a debris field about 1,600 feet from the bow of the Titanic, the search team found the front and back portions of the pressurized hull, said Paul Hankins, who leads salvage operations for the U.S. Navy. Carl Hartsfield of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution said the debris indicates that the submersible probably imploded before reaching the ocean floor.

Pressure from repeated dives to the Titanic wreck might have weakened Titan's hull, said Don Walsh, an oceanographer who was the first submersible pilot in the U.S. Navy.

"They got away with it for a couple of years," he said. "It was not a question of if, but when."

Andrew Von Kerens, a spokesman for OceanGate, when asked for a comment Wednesday said: "We are unable to provide any additional information at this time."

'Guardrails'

OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, who was piloting the Titan during its fatal voyage, had previously expressed his belief that innovation requires disrupting norms.

Before the Passenger Vessel Safety Act of 1993, tourist submersibles could be piloted by anyone with a valid U.S. Coast Guard captain's license. But the law created new regulations for vessels diving deep, so long as they set off in American waters or fly a U.S. flag - Titan did neither.

Rush told Smithsonian Magazine in June 2019 that the law was well intended, but was overly cautious by putting passenger safety over commercial innovation.

"There hasn't been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years," he told the magazine. "It's obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn't innovated or grown - because they have all these regulations."

Rush was piloting the Titan when it lost contact with its mother ship Sunday, the company said. The vessel had visited the Titanic wreck in previous years.

Vessels that dive to areas of extreme pressure can experience damage to their hulls over time, Mercogliano said. Periodic inspections from a classification agency are crucial to maintaining safety, he added.

Titan did not undergo that classification process, according to OceanGate.

In 2019, the company published a blog post titled "Why Isn't Titan Classed?" In it, the company said most marine accidents were the result of operator error - not mechanical failure.

"As a result, simply focusing on classing the vessel does not address the operational risks," the blog post reads. "Maintaining high-level operational safety requires constant, committed effort and a focused corporate culture - two things that OceanGate takes very seriously and that are not assessed during classification."

Questions about the regulatory and safety standards of OceanGate were raised in 2018 when the company sued a former employee and accused him of sharing confidential information, according to court documents reviewed by The Washington Post.

David Lochridge, former director of marine operations at OceanGate, filed a counterclaim for wrongful termination. He alleged that OceanGate refused to pay a manufacturer to build a window that would meet the required depth of 4,000 meters, or more than 13,000 feet, the depth needed to reach Titanic, according to court filings.

Lochridge also alleged that he had expressed concerns about the quality control and safety of the Titan, and he encouraged OceanGate to use the American Bureau of Shipping to inspect and certify the submersible. Lochridge and OceanGate settled the lawsuit in 2018.

OceanGate declined to comment on the lawsuit and allegations. In court records, OceanGate said it had special monitors that would identify cracking in the hull if Titan was close to failure. Lochridge declined to comment when reached through his attorney, but he said he was praying for those aboard Titan.

A group of industry professionals also raised concerns about Titan not undergoing the certification process in 2018, according to William Kohnen, president and CEO of the engineering firm Hydrospace Group.

Kohnen and other members of the Marine Technology Society debated sending Rush a letter urging him to go through the classification process, warning that a "single negative event could undo" decades of safe exploration in underwater vehicles. The group, Kohnen said, ultimately never sent the letter, which was first reported by the New York Times.

"That process is an accumulation of knowledge that is our safety guideline," said Kohnen, who called Rush at the time to make the same plea the letter did. "These are our guardrails."

'Explosion in reverse'

Several deep-sea exploration experts say they wouldn't have trusted Titan's hull, which was made of mostly carbon fiber wound around titanium.

Carbon fiber is a relatively new material for deep sea applications, said Stefano Brizzolara, professor in ocean engineering at Virginia Tech. Traditionally, vessels are made of steel and titanium, which can better withstand pressure and keep water out.

"Carbon fiber doesn't do that," he said. "It deforms a little bit. And then it immediately and suddenly cracks and breaks."

"The outside pressure is so high that it causes an implosion," Brizzolara added. "A kind of explosion in reverse."

As you go deeper into the ocean, the pressure outside the vessel increases. At 4,000 meters, the pressure is 400 times the atmospheric pressure that humans experience on Earth, he said.

A 2018 blog post on OceanGate's website said the vessel was tested to 4,000 meters. But the use of a new material in the composite hull combined with the lack of outside oversight gave some experts pause - especially if the vessel was being used to transport people.

"For human occupancy, a composite pressure vessel is not something that I would have a lot of confidence in unless there was a serious, serious third-party oversight," David Lovalvo, founder of the Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration, said.

Submersibles are used daily around the world for commercial activities like laying cable and pipe with very few accidents, said Lovalvo, who has been 13,000 feet down several times in his four-decade career.

Even though the classing process is not required if operating in international waters and launching from another vessel, as Titan was, many commercial submersibles still undergo it, according to Lovalvo. They are also made with what he deems safer materials, like titanium, for insurance reasons, he said.

Matt Tulloch, who has been to Titanic four times, said the submersible that he visited the wreck site on was a sphere made of titanium.

When asked about the industry's opinion of OceanGate, he said: "It was a company that was innovative and was pushing the boundaries of traditional safety," but added: "They were not as cavalier as some of the reports seem to portray them as."

Tulloch said he was close friends with and deeply trusted Paul-Henri Nargeolet - one of the five people who perished aboard Titan - for 30 years. They met through Tulloch's father, George Tulloch, who funded the first salvage mission to Titanic.

Matt Tulloch said Nargeolet, an experienced French mariner, has earned the title "Mr. Titanic" because of his scores of trips down deep.

"There is a fair assessment to be made that these guys were pushing the limits, and I say that as neutrally as I can. Because in this domain, there's always this getting to the next level, and to do that you have to push it to the limit," Tulloch said.

Walsh, the former Navy submersible pilot, said the decision to have a carbon fiber hull, rather than a metal like titanium, was risky.

"God bless them if they want to do experimental stuff, but for God's sake don't take members of the public down while you're doing that," Walsh said.