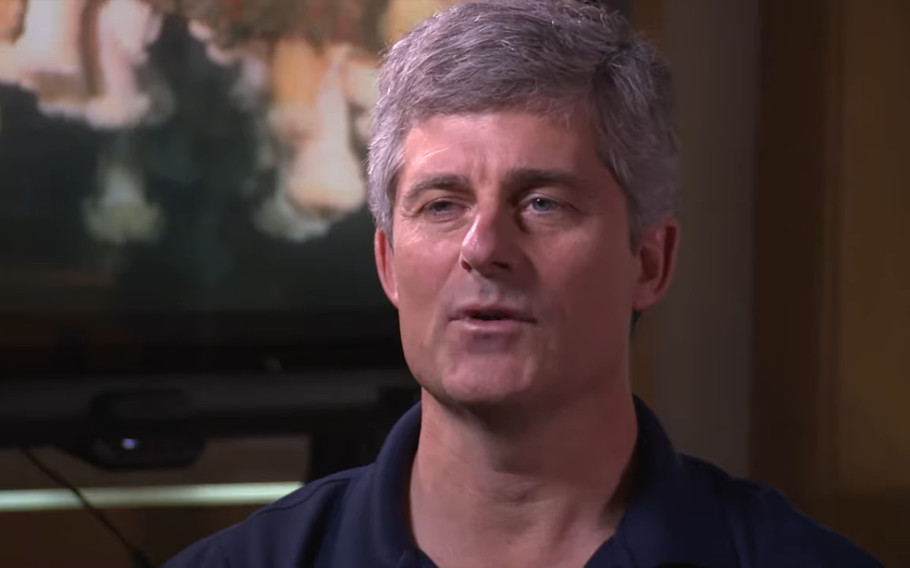

A screenshot of a video featuring OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush on March 13, 2015. Rush publicly talked about how he had “broken some rules to make” the submersible, noting his use of carbon fiber — a relatively new material for deep sea applications that experts say isn’t as proven as steel and titanium at withstanding pressure during deep dives. (Youtube)

If not for a birthday party and a speaking engagement, Arnie Weissmann says he would have probably been one of the passengers aboard the Titan submersible that imploded in the North Atlantic, killing all five people aboard.

Weissmann, editor in chief of Travel Weekly, said he was ready to accept an invitation from OceanGate for the June trip to explore the wreckage of the Titanic before a scheduling conflict arose. The May trip he took instead had its dive canceled due to bad weather, but Weissmann said he was struck by a conversation he had over cigars with OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush that has haunted him in the days after the submersible first went missing.

As they puffed their Cuban cigars on the back deck of the submersible’s mother ship, the Canadian research ship Polar Prince, the night before the scheduled dive, Weissmann said Rush told him how he had gotten the carbon fiber used to make the Titan, specifically the hull of the vessel, “at a big discount from Boeing.” Weissmann wrote in Travel Weekly that Rush said he was able to get the carbon fiber at a good rate “because it was past its shelf life for use in airplanes.”

Rush had hailed the lighter carbon fiber as an innovation in a field that has long relied on more expensive titanium, and claimed the company had worked with Boeing to make sure the pressure vessel, the carbon-fiber tube that keeps passengers alive, was safe. But the carbon fiber and the shape of the Titan had raised concern among maritime regulation experts and experienced mariners. And Weissmann said he felt that the man who he thought was going to lead him on a 13,000-foot dive to the ocean floor came off as “cocky” when talking about safety.

“I responded right away, saying, ‘Don’t you have any concerns about that?’” Weissmann, 69, recalled to The Washington Post. “He was very dismissive and said: ‘No, it’s perfectly fine. Having all these certifications for airplanes is one thing, but the carbon fiber was perfectly sound.’”

Weissmann added, “I think if I had known everything I know today, I would not have gone. It’s so sad that this aspect of his character is how I think people will ultimately judge him, but it is certainly right that he needs to be held accountable for his actions.”

Boeing said in a statement to The Post on Friday that the company had no role in working with OceanGate on the submersible.

“Boeing was not a partner on the Titan and did not design or build it,” a spokesperson said.

The spokesperson also said that “Boeing has found no record of any sale of composite material to OceanGate or its CEO.”

Andrew Von Kerens, a spokesman for OceanGate, declined to answer the same question, pointing to the company’s statement after the Coast Guard announced Thursday that the submersible vessel underwent a “catastrophic implosion” that killed all aboard.

“The entire OceanGate family is deeply grateful for the countless men and women from multiple organizations of the international community who expedited wide-ranging resources and have worked so very hard on this mission,” the company’s statement read. “We appreciate their commitment to finding these five explorers, and their days and nights of tireless work in support of our crew and their families.”

Many questions remain as to how OceanGate’s Titan skirted regulations and oversight until the underwater tragedy struck hundreds of miles off the coast of Newfoundland. Rush, whose safety protocols have been called into question, had told CBS News last year that his greatest fear was being in a submersible during one of his company’s expeditions and facing “things that will stop me from being able to get to the surface.”

Yet, Rush remained confident when he was asked by CBS correspondent David Pogue about how elements of the submersible appeared improvised. Pogue likened the vessel to something people would see on “MacGyver,” a show whose titular character is known for ad hoc tool design.

‘There’s certain things you want to be button downed, so the pressure vessel is not ‘MacGyver’d’ at all,” Rush said in the interview. “Everything else can fail: Your thrusters can go, your lights can go, you’re still going to be safe.”

In addition to Boeing, Rush claimed on national television that his company worked with NASA and the University of Washington to make sure the submersible was in good shape. NASA said in a statement Friday that its personnel were consulted on the manufacturing process but did not conduct testing or help build the vessel with its personnel or facilities.

Rush also publicly talked about how he had “broken some rules to make” the submersible, noting his use of carbon fiber — a relatively new material for deep sea applications that experts say isn’t as proven as steel and titanium at withstanding pressure during deep dives.

“I think I’ve broken them [rules] with logic and good engineering behind me,” Rush said in a previous interview.

Weissmann had seen a lot in his decades-long career in travel journalism. But he was intrigued by the email he got from Wendy Rush, the CEO’s wife, inviting him to take a trip on OceanGate’s submersible.

“I get a lot of things come through my inbox, and I hadn’t seen anything quite like that,” Weissmann said.

He originally scheduled his trip for June, excited about the prospect of potentially diving to the wreckage of the Titanic. When he figured out he had to be in California the day after the trip’s projected conclusion, Weissmann knew it would be tight and decided to move up the expedition to late May, he said.

During his training, Weissmann realized he knew not only Stockton Rush but also former French navy commander Paul-Henri Nargeolet. He later found out that another friend, British businessman Hamish Harding, was scheduled for the June trip that Weissmann had originally scheduled.

While on the May trip, Weissmann said he asked Nargeolet, an experienced explorer of the Titanic wreckage, if he was worried about anything going wrong during a deep sea dive. Weissmann wrote in Travel Weekly that Nargeolet told him he wasn’t concerned.

“Under that pressure, you’d be dead before you knew there was a problem,” Nargeolet said with a smile, according to Weissmann.

After the trip, Weissmann said he ran into Harding, who inquired about what to expect while on the Titan.

“He asked me how was it and how was the operation,” the journalist said. “I was candid with him about how every day there was an endless list of things that needed to be worked on about the sub.”

Weissmann’s eight days with Rush had him see the CEO as a “three-dimensional human being,” he said. In one moment, Rush showed why he was “a leader of his team who was caring, inclusive, thoughtful and even risk-averse,” Weissman said. In others, Weissmann noted how Rush could appear too confident.

“I only knew him for eight days, but I saw another side of him,” Weissmann said. “And I think that side of him is going to be lost because it’s so overshadowed by what ultimately, and literally, was a fatal flaw.”