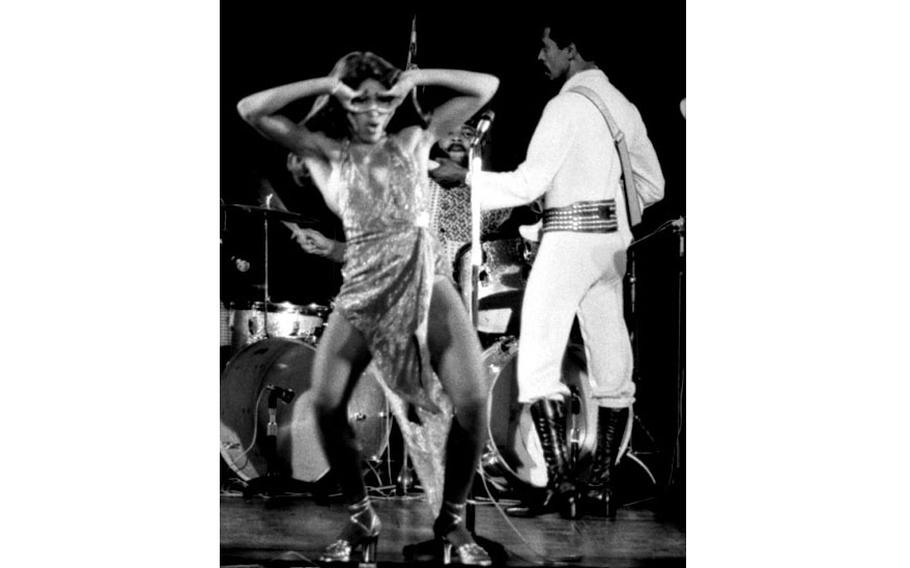

Tina Turner onstage in 1972 at Frankfurt’s Jahrhunderthalle, backed up by then-husband Ike and his band. (Cal Posner/Stars and Stripes)

She may have had second billing in her own group, but everyone knew who the star of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue was.

It was Tina Turner the world came to see, when she and her husband, Ike, toured with the Rolling Stones in the 1960s and scored a Grammy-winning hit with “Proud Mary” in 1971.

It was Tina Turner who ignited the stage with her raw voice and her frenzied, sweat-soaked dancing, as she became one of the most dynamic and influential performers in popular music.

And it was Tina Turner who, after walking away from the spotlight and her volatile, abusive husband, remade herself as a solo artist, selling more than 100 million records, winning eight Grammy Awards and becoming a brighter star in her 40s and 50s than she had been in her youth. Her overtly sexual costumes, dance moves and persona were imitated by performers across generations, from Mick Jagger to Beyoncé to Cardi B.

Turner, whose saga of struggle and revival was defiantly expressed in her 1984 hit song “What’s Love Got to Do With It” and a best-selling autobiography, “I, Tina,” died May 24 at her home in Küsnacht, Switzerland, near Zurich. She was 83 and, in recent years, she had a stroke, kidney disease and other ailments. Bernard Doherty, her longtime publicist, confirmed the death but did not provide an immediate cause.

Turner, who grew up as Anna Mae Bullock in rural Nutbush, Tenn., was living in St. Louis in the late 1950s, when her older sister arranged an introduction to Ike Turner, who was performing at a local club.

He was already an established musician at 26 and had co-written a 1951 rhythm-and-blues hit, “Rocket 88,” featuring his hard-driving piano, that is sometimes called the first rock-and-roll record. At first, Turner, then 18, was put off by Ike’s gaunt, unsmiling appearance.

“I remember thinking that I had never seen anyone that skinny,” she told Rolling Stone magazine in 1986. “But when he walked out, he did have a great presence ... boy, could he play that music. The place just started rocking. I wanted to get up there and sing sooooo bad.”

During an intermission, the band’s drummer — her sister’s boyfriend — set up a microphone, and Turner sang a song by B.B. King.

“Well, when Ike heard me,” she told Rolling Stone, “he rushed over to me and said, ‘Girl, I didn’t know you could sing!’ The band came back, and I kept singing.”

She began to work with Ike’s band, the Kings of Rhythm, but was not spotlighted until 1960, when a male singer didn’t show up for a studio recording session. Turner stepped up to the microphone to sing “A Fool in Love,” a song written by Ike.

It was meant to be just a demo recording, but Turner’s impassioned performance was released on a small label and credited to “Ike & Tina Turner” — a stage name bestowed by Ike. He chose the name because Tina rhymed with “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle,” a scantily clad, vine-swinging character in comic books and a 1950s TV series.

“A Fool in Love” sold 800,000 copies, became a No. 2 R&B hit and reached No. 27 on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart. The group had a few other minor R&B hits but never quite reached nationwide fame.

Tina Turner onstage in 1972 at Frankfurt’s Jahrhunderthalle, backed up by then-husband Ike and his band. (Cal Posner/Stars and Stripes)

Offstage, Turner was raising four boys — two of her own, and two of Ike’s sons from another relationship. Her older son was from a relationship with Raymond Hill, a saxophonist in Ike Turner’s band; Ike was the father of her second son, born in 1960. She and Ike were married in 1962.

Working on the club circuit, Tina and the Ikettes — three women who were backup singers and dancers — developed a high-energy, dynamically choreographed stage act that made other groups look like statues.

Yet, behind the joyous dancing and music, Turner wrote in her 1986 memoir, “I, Tina,” Ike Turner controlled the group like “a sadistic little cult.” He carried a gun and allowed Turner no financial independence.

As the group’s profile began to rise with an appearance in a 1966 concert film “The Big T.N.T. Show,” Tina Turner caught the attention of music producer Phil Spector, who saw her as a potential star.

A major hitmaker of the early 1960s, Spector was known for his studio wizardry and “wall of sound” musical style. He co-wrote a song with Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, “River Deep, Mountain High,” that he asked Turner to record. Insisting on total artistic control, Spector agreed to credit the recording to “Ike and Tina Turner” if Ike stayed out of the studio.

At the long, nighttime recording sessions, Turner took off her sweat-drenched blouse and was wearing only her bra as she sang countless takes of the vocal track.

“River Deep” begins on a plaintive, introspective note — “When I was a little girl, I had a rag doll” — before building to a frenzied climax: “Do I love you, my oh my? Oh baby, river deep, mountain high!”

Rolling Stone later ranked “River Deep” No. 33 on the magazine’s list of the 500 greatest songs of the rock era. It became a hit in Europe but never caught on in the United States, reaching only No. 88 on the Billboard pop chart.

“It was too black for the pop stations, and too pop for the black stations,” Turner noted in her autobiography.

Still, it marked a turning point for Turner: She realized she didn’t need Ike Turner to make an important record — and that she was a singer with a voice of her own.

“You know why I will always love that song?” she told the Chicago Tribune. “People used to call me a dancer, not a singer. So when I got with Phil, I started charging ahead and he was like, ‘No, no, I just want you to sing.’ “

Singer Tina Turner, left, and Mick Jagger perform together during Live-Aid concert on July 14, 1985, in Philadelphia. (Rusty Kennedy/AP)

In 1966, the Rolling Stones invited the Ike & Tina Turner Revue to join them for the first of several tours, introducing them to a wider audience.

Jagger came into the dressing room Turner shared with the Ikettes, she wrote in a 2018 memoir, “My Love Story,” “and said in his unmistakable voice: ‘I like how you girls dance.’

“We’d seen him strutting with his tambourine onstage, and he was a little awkward back then,” she continued. “We pulled him into our group and taught him how to do the Pony. Mick caught on fast. ... Not that he ever gave me and the girls credit for his fancy new footwork. To this day, Mick likes to say, ‘My mother taught me how to dance.’ And I say, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ But I know better.”

During the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Ike and Tina Turner began to record versions of songs by other artists, including the Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women,” Otis Redding’s “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” and most memorably “Proud Mary,” written by John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival.

In the original recording and in every performance for the next three decades, Turner opened the song with a signature introduction that her audiences recited in unison with her: “We never, ever, do nothin’ nice ... and easy. So we’re gonna do it nice ... and rough!”

“Proud Mary” reached No. 4 on the pop charts in 1971, sold more than 1 million copies and won a Grammy Award for best R&B performance. The group had a minor hit in 1973 with “Nutbush City Limits,” a tune written by Turner about her Tennessee roots, and she released a pair of poorly received solo albums.

But her life in the 1970s was increasingly scarred by her worsening relationship with Ike Turner. He had a drug problem, flaunted his affairs with other women and sometimes beat Tina, leaving her with swollen eyes and, one time, a broken jaw. He used his fists, a folded wire hanger and a wooden shoe tree, or stretcher.

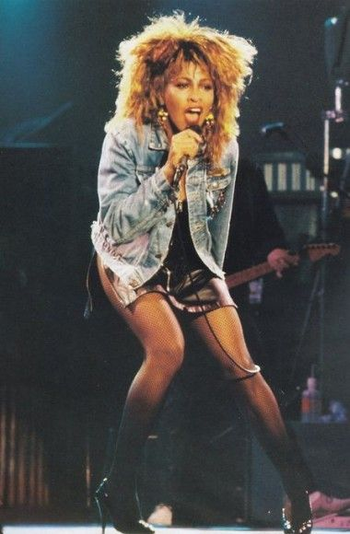

Tina Turner, whose saga of struggle and revival was defiantly expressed in her 1984 hit song “What’s Love Got to Do With It” and a best-selling autobiography, “I, Tina,” died May 24 at her home in Küsnacht, Switzerland, near Zurich. She was 83 (Tina Turner/Facebook)

“I was trapped,” she told Rolling Stone. “The success and the fear came almost hand in hand. When I finally went to tell him that I didn’t want to go on ... that’s when he got the shoe stretcher.”

In 1976, Turner slipped out of her hotel room and down an alley in Dallas, where the band was on tour. She had 36 cents, a gas-station credit card and the clothes on her back. She found refuge with friends, in exchange for cleaning their houses, and lived on food stamps. She began to practice Buddhism, which she said gave a newfound inner peace.

After their divorce in 1978, Tina never saw Ike Turner again. Her financial settlement was not nearly enough to pay off hundreds of thousands of dollars in back taxes and broken concert contracts.

“It’s very difficult to explain to people why I stayed,” she later told The Washington Post. “I’d left Tennessee as a little country girl and stepped into a man’s life who was a producer and had money and was a star in his own right. And at one time, Ike Turner had been very nice to me. It was in the later years that he changed to become a horrible person.”

She began to appear on TV game shows and in Las Vegas lounges. In 1979, Turner found a new manager, Australian Roger Davies, who had helped guide Olivia Newton-John’s career. With Turner, he became the architect of one of the most remarkable comeback stories in show business.

Davies arranged for Turner to open for the Rolling Stones in 1981, and her cover version of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” became a hit in England and in U.S. dance clubs. Yet, as late as 1983, she still didn’t have a recording contract with a major label.

That year, David Bowie told executives of Capitol Records that he had to skip a Manhattan party in his honor because his favorite performer was appearing at a nightclub.

“So they all came along and voilà’ — there I was onstage,” Turner told The Post. “They signed me simply because of David.”

Released to modest expectations in 1984, her album “Private Dancer” sold tens of millions of copies. Turner won three Grammy Awards, including Record of the Year, for the album’s top single, “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” which was her only No. 1 hit as a solo artist.

At first, she was reluctant to sing the tune, by two British songwriters, until she found the right vocal treatment, pitched somewhere between a snarl and leering come-on:

What’s love got to do, got to do with it

What’s love but a secondhand emotion

What’s love got to do, got to do with it

Who needs a heart when a heart can be broken?

Then in her mid-40s, Turner became an international superstar, acclaimed for the next 25 years for her breathtaking performances, in which she wore elaborate wigs and skimpy miniskirts that showed off her well-toned legs.

Tina Turner grew up as Anna Mae Bullock in rural Nutbush, Tenn. (Tina Turner/Facebook)

“Everything I’ve done for my act has really been so practical,” she told Rolling Stone in 1986. “The short dresses work for me onstage because I’ve got a short torso and because there’s a lot of dancing and sweating. ... I never advertise myself for men. I always work to the women, because if you’ve got the girls on your side, you’ve got the guys.”

Turner’s 1986 memoir (written with Kurt Loder) formed the basis of an Oscar-nominated 1993 film, “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” with Angela Bassett portraying Turner and Lawrence Fishburne as Ike Turner.

Turner collaborated with U2’s Bono on the theme song for the 1995 James Bond movie “GoldenEye” and appeared at the 2000 Super Bowl. She retired from performing in 2009, the year she turned 70.

Anna Mae Bullock was born Nov. 26, 1939, in Brownsville, Tenn., and spent her childhood in nearby Nutbush. Her father was a farm overseer, and her mother was a beautician, among other jobs.

Her parents had a tempestuous relationship and often lived away from the family, leaving young Anna Mae with grandparents and other relatives on farms in western Tennessee. “I wasn’t sad about it,” she told Rolling Stone in 1986. “It was just a fact that my parents didn’t care that much for me.”

In the 1950s, Turner was reunited with her mother, who was working as a maid in St. Louis. After finishing high school, she worked in a hospital before launching her music career.

Turner had several acting roles in films, first playing the Acid Queen in Ken Russell’s 1975 production of the Who’s rock opera, “Tommy.” A decade later, she appeared opposite Mel Gibson in the dystopian film “Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome,” which featured her hit song “We Don’t Need Another Hero.”

She turned down a role in Steven Spielberg’s 1985 film “The Color Purple,” which featured abusive men in the rural South, saying “I lived that story. I don’t need to act it.”

Turner was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, along with Ike Turner, in 1991. (Ike was in prison at the time on drug charges. He died in 2007.) She received the Kennedy Center Honors in 2005 and was named to the Rock Hall a second time, as a solo performer, in 2021.

In 1986, Turner met German music executive Erwin Bach, who was 16 years younger. They lived together for years before marrying in 2013. Turner had several serious health problems, including a stroke and kidney dialysis, in her 70s. Bach donated one of his kidneys to Turner in 2017.

Survivors include her husband. Her oldest son, Craig Turner (originally Craig Hill), died by suicide in 2018. “I still don’t know what took him to the edge,” Turner told the BBC. Another son, Ronnie Turner, died in 2022.

Despite her sensuous stage persona, Turner said the person she admired most was the soft-spoken, well-coiffed first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

“My taste was high,” she told Rolling Stone. “So when it came to role models, I looked at presidents’ wives. Of course, you’re talking about a farm girl who stood in the fields, dreaming, years ago, wishing she was that kind of person. But if I had been that kind of person, do you think I could sing with the emotions I do? You sing with those emotions because you’ve had pain in your heart.”