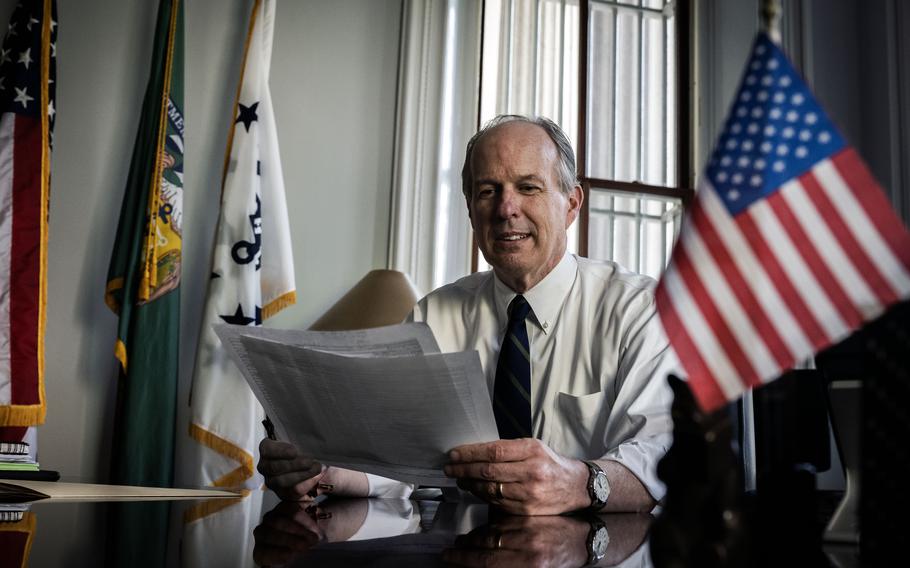

David Lebryk, who is fiscal assistant secretary of the Treasury Department, sits in his office in Washington. (Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post)

At the beginning of every workday, from his second floor office in the U.S. Treasury Department, Dave Lebryk starts his morning looking at a color-coded dashboard tracking the most critical operations of the largest payment system in the world.

More than $6 trillion flows out of the Treasury every year in payments, salaries and purchase orders, and more than $5 trillion flows in, mostly through tax collections and fees. Lebryk’s job is to make sure that these billions of transactions go smoothly. The dashboard, chock full of information from the thousands of employees under his purview, helps him keep track of it all, with green showing where functions are normal, yellow for where issues are emerging and red for problems requiring his immediate attention.

His attention is in particularly high demand these days. The Treasury’s fiscal assistant secretary since 2014, Lebryk is the government staffer perhaps most responsible for figuring out how the United States should handle the alarming prospect of running out of money, making him a pivotal, if lesser-known, player in the debt ceiling standoff consuming Washington.

Lebryk, for instance, provides the financial estimates to Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen, which are then sent to Congress as warnings of the “X date” deadline by which the nation will have exhausted its funds. He plays a crucial role in coordinating and determining how much money the Treasury needs to borrow to finance the government. His team also prepares and manages the “extraordinary measures” that the Treasury has been deploying since January to delay a default for as long as possible.

“He runs the nation’s checkbook. He is not quite the CFO of the country, but he is pretty close,” said Mark Mazur, who served as assistant secretary for tax policy at the Treasury earlier in the Biden administration. “His job is basically trying to keep the system running as long as possible, to push off the day of reckoning as long as possible.”

In calmer times, Lebryk meets once a quarter or once a month to tell Yellen exactly how much money the United States has on hand. But with the federal government running out of money, over the last several months Lebryk and his team have been briefing Yellen every day, as the former Federal Reserve chair responds with detailed questions about their projections. “We take this responsibility enormously seriously,” Lebryk, 61, said in a recent interview.

His analyses could hold even more weight in the days to come and be subject to even more intense scrutiny. Congress sets the maximum amount the Treasury can legally borrow, which is now $31.4 trillion. Because the nation routinely spends more than it collects in revenue, the debt ceiling must be raised to prevent a government default, which many economists predict could cause a global financial crisis.

President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) are negotiating a deal aimed at setting government funding levels and lifting the debt ceiling, but time is running out, and major obstacles remain between the two sides.

If the deal falls through and Congress fails to raise the debt limit in time, Lebryk will likely be at the center of deciding how to structure the payments the government can still make. Even though tax revenue will continue to come into government coffers, it would not be enough to cover all the payment obligations Congress has legally obliged the government to make.

The Treasury would be in the unprecedented circumstance of having to choose which checks to cut. They would have to pick, for instance, between making payments to seniors on Social Security and families in need of food stamp benefits.

Lebryk and his team would be expected to draft recommendations to Yellen and other political leaders laying out the options for managing an unprecedented default, according to former Treasury officials. “If that day comes, he would be in completely uncharted territory, with no guidebook,” Mazur said. “It would be up to him, and his team, to prepare the options of which bills to pay for Secretary Yellen.”

A lifelong government bureaucrat, Lebryk has spent a career preparing for a moment like this one. Raised in Valparaiso, Ind., by a single mother, Lebryk graduated from Harvard with an economics degree, where he also played wide receiver for the football team, before receiving a master’s degree in public administration from the university’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

He joined the Treasury Department in 1989 as a presidential management intern, and has spent the subsequent three decades in government service, under 11 different Treasury secretaries, as well as working as a special assistant at treasury to Jerome H. Powell, who would go onto become the chair of the Federal Reserve. He returns once a year to Valparaiso, where he golfs with his high school baseball and basketball coaches as part of an annual tradition now in its fourth decade.

Scrupulously apolitical, Lebryk moved through positions that gave him deep exposure to the plumbing of federal financing: deputy assistant secretary for fiscal operations and policy, acting director of the U.S. Mint, commissioner of the Bureau of the Fiscal Service. All were civil service jobs that do not require nomination by a president or confirmation by the Senate.

Former colleagues say he is friendly and funny, exceedingly calm under pressure, and unusually straightforward for an assistant secretary, in part because he is a career bureaucrat who is not angling for a political promotion. Some former colleagues also pointed out Lebryk could be making millions of dollars on Wall Street but has instead for three decades earned a government salary.

“I could not, to this day, tell you his politics,” said Michael Faulkender, who served as assistant secretary for economic policy during the Trump administration. Faulkender worked closely with Lebryk when Treasury was tasked with figuring out how to send tens of millions of stimulus payments during the coronavirus pandemic, an effort Lebryk helped lead. “He always seemed to be relaxed and under control.”

Few situations could prove more stressful for Treasury officials than the one now facing Lebryk and his team. The last time the United States neared a default, under the Obama administration in 2011, the stock market contracted by 20 percent. The bond market could be thrown into a panic. The economy could head toward a recession.

Lebryk will have to provide precise information amid the chaos. Every morning, he meets with the career officials at the Office of Fiscal Projections to discuss how much money the government has compared to what had been forecast the previous day. This effort requires sifting through a vast sea of information. There are 438 federal agencies and subagencies, and his team needs to know which ones spent more, or less, than they were expected to do.

The federal government makes 1.4 billion individual payments every year, on everything from worker and military personnel salaries to food safety inspectors and infrastructure grants to weapons contracts. Every day, on average, $185 billion flows in and out. The Treasury must make sure the money on hand exceeds the money going out every day.

Lebryk breaks up his team by category, with some officials focused on spending, some on revenue, and some on debts. “We look at our cash position: How have we done relative to our forecast? Do we need to make adjustments to our financing?” Lebryk said. “You have hundreds of variables, and it is the world’s largest enterprise. You are getting information not only from the agencies, but also millions of taxpayers.”

In May, the Treasury said the X date could occur as early as June 1, a number that rattled Congress, although a previous estimate had pointed to “early June.” Yellen noted the revised timing came after “reviewing recent federal tax receipts,” which many budget experts saw as reflecting weaker than expected tax revenue.

Treasury estimates have been greeted skeptically by many lawmakers in Washington, who believe Yellen may be deliberately trying to scare Congress into acting sooner with a premature X date. Larry Kudlow, who served as head of the National Economic Council under President Donald Trump, said on Fox Business last week that the June 1 deadline “may or may not be true.”

Former Treasury officials say comments like that misunderstand the process for producing the numbers, which they maintain is free of political interference. Treasury career staff are cautious, though, and determined to make sure they give lawmakers enough time to act.

“In my time at Treasury, during two different debt limit standoffs, there was never any influence of any political people weighing on the career staff working on this,” said David Vandivier, who served as deputy assistant secretary for budget and tax in the Treasury’s legislative affairs office during the Obama administration and is now executive director of the Psaros Center for Financial Markets and Policy at Georgetown University. “I never saw any political coercion, or even weighing in any way. The numbers are what the numbers are.”

Treasury’s desire to stay above the political fray could be challenged if the nation crashes through the debt ceiling deadline. Already, Republicans have argued that the agency could manage this process by redirecting incoming tax revenue to cover only the most critical government processes, such as paying the interest on government bonds and ensuring seniors receive Social Security benefits.

That is a process that Treasury officials say will prove far more difficult in practice, in part because the department would be thrust into the very uncomfortable position of picking between critical government functions. “Treasury officials have not wanted to do that because of how the markets would perceive any nation paying some bills but not others,” Vandivier said. “And Dave would be right at the epicenter of that.”

Until that day comes, however, Lebryk will tell lawmakers exactly how long they have to avoid a default, whether they listen to him or not. “We have an obligation to make sure that decision-makers have the best available information to make the decisions on the behalf of the American public,” Lebryk said. “Treasury takes this very seriously as an institution” because of “the position it plays in the government and the economy and the world.”