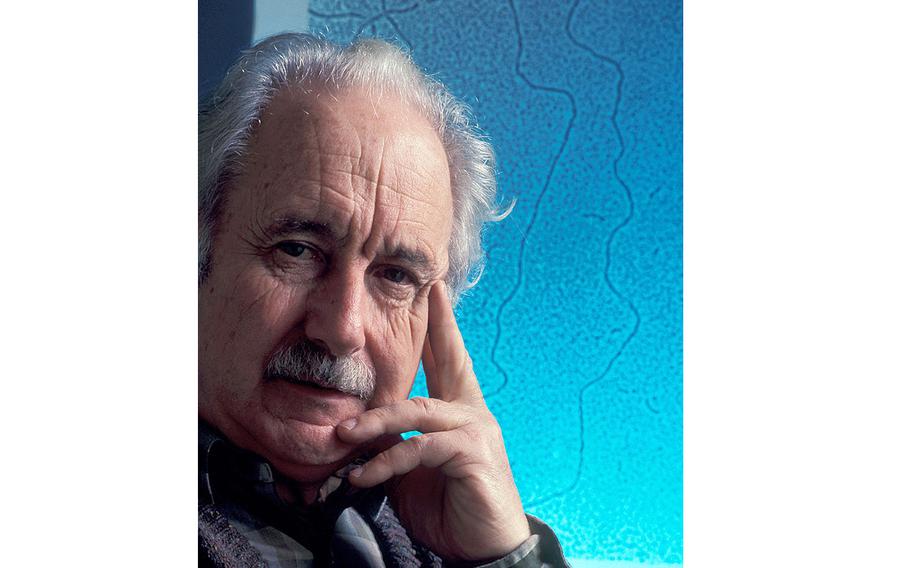

Theodor O. Diener, a Swiss-born scientist whose investigation more than half a century ago of shriveled, stunted potatoes yielded the discovery of the tiniest known agent of infectious disease, died March 28 at his home in Beltsville, Md. He was 102. (Wikimedia Commons)

Theodor O. Diener, a Swiss-born scientist whose investigation more than half a century ago of shriveled, stunted potatoes yielded the discovery of the tiniest known agent of infectious disease, a particle one-eightieth the size of a virus that he named the viroid, died March 28 at his home in Beltsville, Md. He was 102.

His son Michael Diener confirmed his death but did not cite a cause.

Diener immigrated to the United States in 1949 and spent three decades as a plant pathologist at the Agricultural Research Service, the chief internal research agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

President Ronald Reagan awarded him a National Medal of Science for his identification in 1971 of the viroid, an achievement that has been compared in its significance to the discovery of bacteria in the late 1600s and of viruses shortly before the turn of the 20th century.

Since roughly the 1920s, farmers had known of a confounding disease that threatened their potatoes, leaving them shrunken and malformed and reducing the size of a crop by 50 percent or more. In the 1960s and 1970s, according to a report in Forbes magazine, as many as half of the potato plants in some areas of China and Ukraine were sickened.

The condition had a name — potato spindle tuber disease — but its cause proved vexingly elusive.

Working for years with colleagues at ARS, Diener was credited with identifying the infectious agent at the proverbial root of the problem. Using research methods including centrifugation, he determined that the cause was not a virus, as other scientists had speculated, but rather a new, far smaller pathogen — the viroid.

A viroid functions in a manner similar to that of a virus, invading a cell and making it reproduce the viroid’s RNA. Unlike a virus, a viroid has no protein coat. According to the ARS, the long-standing consensus among scientists was that such “naked” pathogens were unable to replicate, even with the aid of an infected cell.

Most scientists also believed that a pathogen as minuscule as the one Diener discovered was incapable of invading an organism. But Diener’s research proved that a viroid — so small that it is barely visible even with an electron microscope — can indeed mount an effective attack.

After identifying the viroid, Diener helped develop a test to detect the one that causes potato spindle tuber disease. Viroids were later found to cause conditions including tomato chlorotic dwarf, apple scar skin, avocado sunblotch and chrysanthemum stunt. There are more than 30 known species of viroids in plant pathology.

Diener’s National Medal of Science, awarded in 1987, credited his discovery with creating “new avenues of molecular research into some of the most serious diseases afflicting plants, animals, and humans.”

Theodor Otto Diener was born in Zurich, in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, on Feb. 28, 1921. His father was a postal employee, and his mother was an accountant. Even in his youth, the future scientist was drawn to plants and animals.

“As a boy, I always kept animals at home: turtles, salamanders, frogs, white mice, hamsters,” he once told an interviewer. “Whereas my parents exhibited a large dose of tolerance to this, neighbors often did not.”

His curiosity led him to ever tinier creatures, he said, after he saved enough money to buy a secondhand Leitz microscope.

Diener studied biology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, receiving a doctoral degree in 1948.

After immigrating to the United States, where he became a naturalized U.S. citizen, he worked as a plant pathologist at Washington State University before joining ARS in Beltsville in 1959. He collaborated on ARS research long after his official retirement in 1988.

He also conducted research and taught at the University of Maryland, where he was a professor emeritus.

In addition to the National Medal of Science, Diener’s honors included election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1977 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978. In 1987, he received the Wolf Prize in agriculture, a $100,000 award given by the Wolf Foundation in Israel.

In addition to his prolific scientific papers, he wrote two books, “Viroids and Viroid Diseases” (1979) and a memoir, “Of Humans, Humanoids and Viroids” (2014).

Diener’s marriage to Shirley Baumann ended in divorce. His wife of 44 years, the former Sybil Fox, died in 2012.

Survivors include three sons from his first marriage, Theodore Diener of Los Angeles, Robert Diener of Urbana, Ill., and Michael Diener of Vienna, Va.; five grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

Like many scientific advances, Diener’s discovery of the viroid was the successful result of many earlier unsuccessful tries. Reflecting on his efforts to decode potato spindle tuber disease, he wryly told the New York Times, “we went up the garden path many times.”