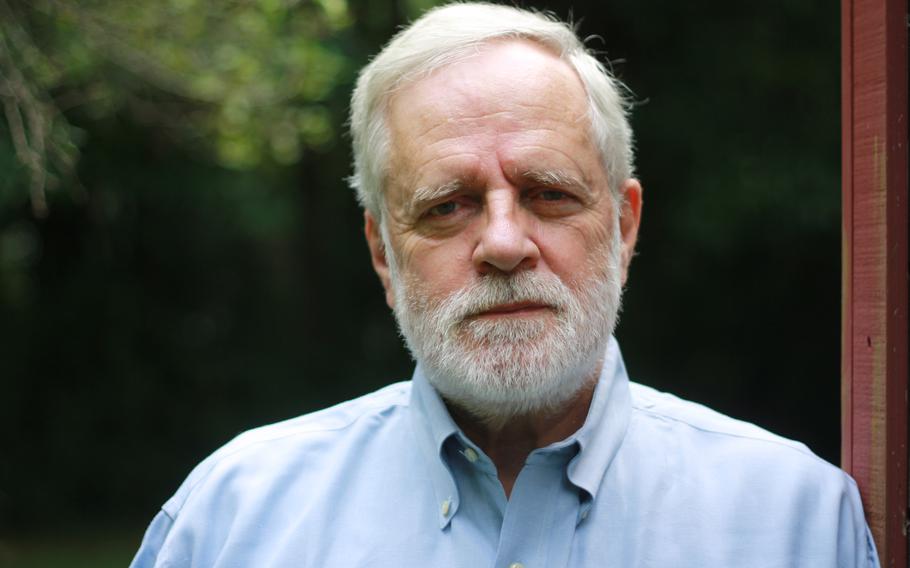

Allan A. Ryan ran the U.S. Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations, a unit designated to find and expel anyone in the United States who had assisted the Nazis. (Andrew Ryan)

Following World War II, thousands of Nazi collaborators masquerading as war refugees immigrated to the United States with new identities. They worked as farmers or butchers or assembly-line workers. Some had fenced-in backyards.

Allan A. Ryan hunted them down.

Ryan, who died Jan. 26 at 77, ran the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, a unit designated to find and expel anyone in the United States who had assisted the Nazis. During his tenure from 1980 to 1983, Mr. Ryan and his team followed leads around the world, including taking depositions of witnesses in the Soviet Union.

Pursuing at least 25 deportation proceedings, Mr. Ryan won cases against Feodor Fedorenko, a guard in the Treblinka extermination camp in Nazi-occupied Poland discovered in Connecticut working at a brass factory, and Wolodymir Osidach, a Ukrainian police officer who rounded up Jews and immigrated to Philadelphia, where he worked in a slaughterhouse.

“The kind of people we’re dealing with were, by and large, very brutal killers for several years in their lives and have turned into model citizens here,” Ryan told the Boston Globe. “They don’t have Nazi museums in their basements. They have a lot to hide in their pasts, and the way you do that is to lay low and not call attention to yourself.”

These collaborators, including concentration camp guards and others directly involved in killing millions of Jews, infiltrated displaced persons camps after the war and then immigrated to the United States under a policy granting such victims refuge.

The presence of collaborators in the United States was ignored for years, Ryan maintained, because of antisemitism and general apathy toward the plight of Jews during the war.

“There was never any effort made by the Immigration and Naturalization Service to investigate the presence of ex-Nazis in America,” Ryan said during a 2002 lecture at the Miller Center for Holocaust Studies at the University of Vermont. “Indeed, there was no demand that it do so - not from Congress, not from the media, not from the public, not from the opinion leaders.”

But in the 1970s, children of Holocaust survivors became politically and socially active, helping move the country toward more public acknowledgment of Nazi atrocities. A new generation of lawmakers became concerned that Nazi collaborators were hiding in plain sight among Americans. In 1979, they pushed the Justice Department to establish the new unit.

Ryan, who clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White, was an assistant to the Solicitor General when Justice Department officials tapped him as the unit’s second director. He paired prosecutors with Holocaust historians, including Raul Hilberg, the author of “The Destruction of the European Jews.”

“We were not going to win cases by convincing the judge that here’s a guy who had cheated on his immigration forms,” Ryan said in a Justice Department report on the unit’s history. “We’d only win cases if we’d convince the judge that here was a war criminal with blood on his hands.”

Hilberg was the first witness in many of Ryan’s cases, including against Osidach. The Ukrainian man arrived in the United States in 1949 and became a citizen in 1963.

“The following summer,” Ryan wrote in his book “Quiet Neighbors: Prosecuting Nazi War Criminals in America,” “a Soviet newspaper accused Osidach of having been the commandant of the Ukrainian police in Rava Ruska from 1942 to 1944, responsible for seeing that the Jews of that town were systematically and efficiently slaughtered.”

The FBI tipped off immigration officials, who visited Osidach. He denied the report and investigators closed the case. The Justice Department unit re-examined the file and brought proceedings against him.

At trial, Jews who escaped from Rava Ruska testified against Osidach. A judge found him guilty, stripping his citizenship. Osidach died two months later from a heart attack - before he could be deported. (Fedorenko was deported to the Soviet Union and executed.)

Ryan bristled at suggestions that his prosecutions were symbolic or unnecessary after so many years gone by.

“I am uncomfortable at any suggestion that the prosecution of Nazi criminals is one aspect of the government’s greater efforts to see that the Holocaust is not forgotten,” Ryan said during his University of Vermont lecture. “We do not place people on trial as a symbolic gesture, or to serve some larger purpose of conscience. We put them on trial because they broke the law.”

Allan Andrew Ryan Jr. was born in Cambridge, Mass., on July 3, 1945, and was the oldest of eight children. His father was a certified public accountant; his mother was a homemaker. He received a bachelor’s degree in government from Dartmouth College in 1966 and graduated from the University of Minnesota law school in 1970. He also served as a captain in the Marines.

In addition to chasing Nazi collaborators, Ryan was appointed in 1983 to investigate whether Army intelligence officers aided Klaus Barbie, a notorious SS officer based in France and working as a paid informant after the war for the Allies, in escaping from Europe.

Ryan’s 218-page report concluded that Army officers hid and then smuggled him to South America. The U.S. government apologized to France, and he was soon expelled from Bolivia to stand trial in France. Barbie was convicted in 1987 of crimes against humanity and died in 1991.

Following his investigation of Barbie, Ryan left government for private practice and settled back in the Boston area, where he worked as a lawyer for Harvard University. He also taught law at Harvard’s extension school and Boston College.

Ryan maintained a keen interest in international law and human rights, advising the Rwandan government on prosecuting those behind the country’s genocide. He also wrote a book about war atrocities in the Philippines in 1944 and 1945.

Ryan died at his home in Norwell, Mass., from a heart attack, his daughter, Elisabeth Ryan, said.

In addition to his daughter, who lives in Brighton, Mass., survivors include his wife of 44 years, the former Nancy Foote, and son Andrew Ryan of Weymouth, Mass.

Elisabeth Ryan said her father instilled in his children a “very acute sense of justice and injustice.”

“Even if you think there’s nothing you can do about it,” she said, “there always is something.”