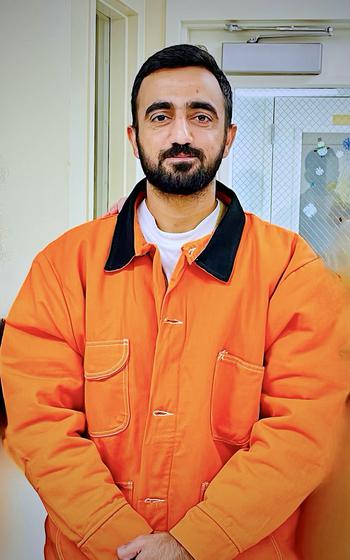

Abdul Wasi Safi, 27, served as an intelligence officer for the special operations corps of the U.S.-backed Afghan defense forces, according to a letter by his superior provided to Stars and Stripes. Safi is seeking asylum in the U.S. but remains detained near the Texas border. (Sami-ullah Safi)

More than 2,000 of Afghans, including some who fought the Taliban alongside American forces during 20 years of war, are among those hoping to claim asylum at the United States’ southern border.

Their plight is a tragic collision of dysfunctional U.S. military and immigration policies, analysts and advocates say.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection logged 2,177 encounters with Afghans on the southern border from October 2021 to the end of 2022, according to numbers provided to Stars and Stripes.

After arriving at the border, some Afghans are allowed entry and can reunite with family members as they wait for the resolution of their asylum cases.

Others are detained. Some 173 Afghans are in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody as of Jan. 9, 2023, the agency said.

Among those detained is an Afghan soldier who walked from Brazil to Texas and whose case has drawn pleas from veterans groups and lawmakers asking for his release.

Abdul Wasi Safi, 27, served as an intelligence officer for the special operations corps of the U.S.-backed Afghan defense forces, according to a letter by his superior provided to Stars and Stripes.

Wasi, as he is known, feared retribution from the Taliban after the fall of the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan in 2021. But he couldn’t get aboard one of the flights out of Kabul during the chaotic evacuation that followed.

Wasi hopped between safehouses over the next year, a situation that pained the U.S. veterans in America who tried to bring him out of the country.

“Lt. Wasi served shoulder-to-shoulder with U.S. special operations soldiers,” said Daniel Elkins, who is founder of the Washington-based Special Operations Association of America. “We know that more people would be buried in Arlington (National Cemetery) if not for people like Wasi.”

Family members and veterans groups paid for Wasi to flee to Pakistan and then Brazil, according to the Texas Tribune, which began reporting on the issue in November.

In late July, Wasi flew to Sao Paulo and then three weeks later joined other migrants making the journey to the U.S., the Texas Tribune reported.

Wasi said he was robbed, tortured and beaten along the way, according to a Fox News report in December.

On Sept. 30, Wasi crossed the Rio Grande into the United States. Court documents state that he carried a letter of recommendation, his education records and a military ID.

His brother, a U.S. citizen living in Houston, said Wasi was expecting a hero’s welcome. Instead, Wasi was arrested when he tried to claim asylum and was charged with a federal crime for illegally entering the country.

He now sits in a jail cell in Eden, Texas.

Sami-ullah Safi, 29, the brother of an Afghan intelligence officer detained after crossing into the U.S. from Mexico, said at a press conference in Houston on Jan. 13, 2023, that his brother should receive asylum in the U.S. due to fears of Taliban retribution. (Sami-ullah Safi)

Inherent contradictions

Immigration advocates and analysts as well as Wasi’s lawyers say the case illustrates inherent contradictions in American asylum policies.

The U.S. allows people from other countries to seek protection within its borders if they have suffered persecution or fear that they will be persecuted in their home countries.

Asylum seekers must be physically present in the United States. Those who were evacuated during the U.S. military airlift in 2021 could request asylum upon arrival in America.

But those still in Afghanistan must find another way there.

“Everyone is angry that people are going to the southern border, but that's the way to do it,” said Jennifer Cervantes, an immigration lawyer representing Wasi.

The U.S. asylum system is outdated, said Adam Isacson, a director at the human rights group Washington Office on Latin America.

Border protection agency authorities said they logged more than 2 million people along the border during fiscal year 2022, a record high.

The U.S. released a plan in December to surge nearly 1,000 Border Patrol processing coordinators for asylum seekers, a CNN report then said.

Nevertheless, the U.S. has “failed to adjust to today’s greater demand” and changing needs at the border, Isacson said.

A “typical” migrant was once judged to be a single Mexican adult looking for work, not someone with a credible claim of fear, Isacson said.

Just 15% of migrants at the U.S. southern border came from countries other than Mexico in 2012, but that number rose to 80% of migrants in 2019, according to research published in November by Isacson’s organization. These migrants come from other countries in Central America as well as Eastern Hemisphere countries such as Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

“The main connection between asylum seekers of different nationalities is that all find themselves caught up in our Kafkaesque, backlogged, underfunded asylum system,” Isacson said.

Abdul Wasi Safi, 27, faces federal misdemeanor charges for crossing the U.S. southern border without authorization. Safi and his supporters said he wanted to claim asylum in the U.S. out of fear of retribution from the Taliban due to his service as an intelligence officer in the U.S.-backed Afghan military. (Sami-ullah Safi)

Exile in Mexico

Hundreds of Afghans began arriving in Mexico during the evacuation in 2021, said Daniel Berlin of the New York-based International Rescue Committee.

Some had their visa applications processed and are now living in the U.S. or Canada. But others were stuck waiting for months, Berlin said.

Afghans also were not allowed to work, Berlin said, and had to rely on donations from family and charity organizations.

The group now maintains a community center in Mexico City where anywhere from 60 to 100 Afghan migrants pass through, Berlin said.

He said he’s heard a lot of people wondering whether they should try to cross into the U.S. without any paperwork.

“We try to dissuade anyone from doing that,” Berlin said. “It’s very dangerous.”

Last year was the deadliest on record for migrants trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border, with more than 800 drownings and other fatalities, NPR reported in September.

But Berlin said he understands why people decide to risk their lives to try to get to America.

“There’s not a lot of clear pathways for Afghans, many of whom were promised by the U.S. to enter,” Berlin said. “These processes are not working, and that’s causing people to take risky decisions.”

In this photograph provided by Sami-ullah Safi, Abdul Wasi Safi, bottom right, takes a selfie near the Darien Gap, a stretch of land that separates Colombia and Panama, in the summer of 2022, during his journey to the U.S in 2022. (Abdul Wasi Safi via AP)

The luck of the draw

A person's fate at the border can be decided by something as unpredictable as the mood of the agent processing them, said Giedre Stasiunaite, a Miami-based immigration attorney who has worked on cases for Afghans and others.

They may be deported immediately, put in detention or allowed into the country to begin their asylum claims.

“The most confusing thing to me and to other people is the lack of consistency,” Stasiunaite said. “It shouldn’t be the luck of the draw, and unfortunately it is.”

Wasi landed in what The Associated Press in 2017 called “America's toughest courthouse when it comes to dealing with people who cross the border illegally.”

It’s rare for asylum seekers to be charged, but the U.S. Western District Court in Del Rio, Texas, prosecutes many of those who are arrested, the AP report said.

Wasi’s supporters say he will be killed if he is sent back to Afghanistan but “until his criminal case is finished, we can't move forward with ICE,” said Cervantes, his immigration lawyer.

Wasi’s supporters hope his court case will be dropped. Among them are two dozen veterans groups who wrote a letter on his behalf in December, as well as U.S. representatives Dan Crenshaw, a Texas Republican; Sheila Jackson Lee, a Texas Democrat; and Michael Waltz, a Florida Republican.

“He’s terrified, lonely and definitely feels forgotten,” Elkins said, adding that Wasi needs medical attention for injuries from the beatings he received on his journey.

Sami-ullah Safi, Wasi’s brother, hopes he can host him at his home in Houston. Safi, 29, once worked as a translator for American troops before receiving a Special Immigrant Visa.

He said his experiences with the asylum program on the southern border have jarred his beliefs about his new home.

“My brother and I have stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the United States Armed Forces in Afghanistan,” Sami-ullah Safi said in a text message. “We have risked our safety and our family’s safety to fight terrorism.

“For my brother to show up to the American border and be treated like a criminal and jailed for unknown reasons, defies everything I have ever known about America.”