For nearly two hours, about two dozen people on a group Telegram live stream cried, read Scripture, listened to hymns — and prayed fervently for defendants in jail facing trial for their roles in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

“We pray for unity in those cells,” said one of the group’s leaders, a woman named Aida. “Get close to them, Father God, to protect our brothers.”

This nightly prayer call featured one of many support groups that have formed in the two years since the violent mob — encouraged by former president Donald Trump — stormed the U.S. Capitol building and threatened the country’s peaceful transition of power after Joe Biden’s victory.

Right-wing supporters of the “Jan. Sixers” have formed prayer chains, instigated letter writing campaigns, organized vigils and raised millions for their legal defense — all with the aim of supporting the 932 federally charged defendants they see as valiant patriots, prisoners of conscience persecuted for engaging in their First Amendment rights.

They have persevered despite powerful evidence to the contrary — including judges uniformly excoriating defendants, ongoing guilty pleas and investigations, as well as a recent congressional report showing the extremity of the violence, the detail of the planning and the failure of Trump and other White House officials to quell the riot.

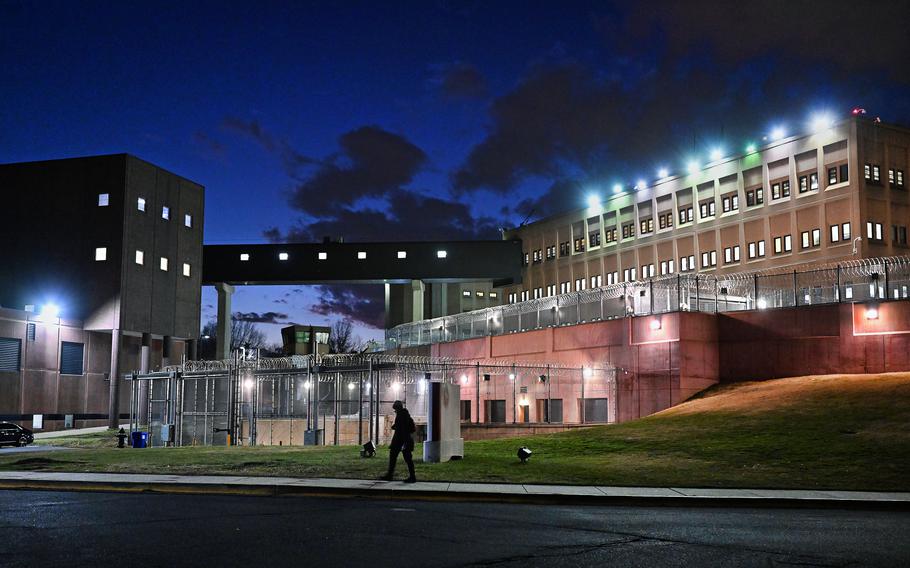

Demonstrators rally Jan. 5, 2022, outside of a Washington jail, where a group of defendants charged in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol are being held. (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

Since 2021, Jan. 6 defendants have raised more than $3.7 million on the Christian crowdfunding website GiveSendGo, according to a Washington Post review of accounts that remain public, and millions more have been raised by umbrella groups in the name of the “patriots” — a flood of money that has raised concerns about fairness and oversight.

“It’s amazing that this movement is really growing by leaps and bounds,” said Ned Lang, a former town councilman from Tusten, N.Y., whose son, Edward “Jake” Lang, pleaded not guilty to charges of beating police officers with a baseball bat during a lengthy assault. The Lang family has raised more than $335,000 through two GiveSendGo accounts, and Jake has his own personal assistant to manage his interview requests and podcast schedule — from jail.

The portrayal of the Jan. 6 defendants as political prisoners is anathema to many outside the far right who haven’t forgotten the five who died in the event, the Capitol Hill police officers slipping on blood as they fought for their lives and the hangman’s gallows rioters constructed before chanting that then-vice president Mike Pence should be hanged for certifying an election they wrongly believed was fraudulent.

“It’s almost like Jan. 6 is baked into the electorate on the far right. When they see Jan. 6, they automatically think peaceful patriots being persecuted as political prisoners,” said Denver Riggleman, a former Republican congressman and senior technical adviser for the House Select Committee that investigated the attack. “It normalizes violence as an acceptable method for political disagreement. In effect, it endorses domestic terrorism. Not to mention that January 6th is a case study in radicalization and actions based completely on fantasy.”

Dozens of times — nightly in the summer months — supporters have held a candlelight vigil at the D.C. jail, where 21 detainees are still housed in a special wing awaiting trial, jail officials said. Amid the flashing blue lights of the security vehicles and the more pallid flickers of their candles, protesters decry the confinement of the men inside and the conditions at the troubled facility, long a concern of human rights activists. At 9 p.m., they sing the national anthem while prisoners above turn the lights of their cells off and on.

Outside the District, anniversary vigils in defense of those incarcerated are planned Friday night in Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Pennsylvania and Texas.

Much of the money flowing to the Jan. Sixers has been ostensibly to support their families while they are away, pay for legal fees and even bolster commissary funds. A review of defendants’ personal GiveSendGo accounts tells sad tales of middle-class American families in ruins, with homes lost, businesses shuttered and savings depleted from legal fees.

Demonstrators gather Jan. 5, 2022, outside of a jail where a group of defendants charged in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol are being held in D.C. (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

There is often little clarity about how money is being spent by some of the larger organizations, according to Jordan Libowitz, the communications director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a nonpartisan U.S. government accountability watchdog. He noted concerns raised by a recent NPR investigation into how one of the biggest nonprofits, the Patriot Freedom Project, was administered.

The organization said in April it had raised a total of $1,164,321 and given out $665,000 to Jan. 6 families for legal fees and other expenses. Its founder, Cynthia Hughes, did not return emails from The Post requesting comment.

“Everybody is raising money off them,” Riggleman said. “We don’t know where the money is going but ... this is just a fantastic moneymaking opportunity.”

Judges around the country have tried to prevent some insurrectionists from profiting off their actions, but even personal defense funds can be problematic, court proceedings show. In December, a federal judge sentenced Ronald Sandlin, 35, a tech entrepreneur from Las Vegas who assaulted police, to 63 months in prison and fined him $20,000 in part because he had raised $21,000 online for his defense. Sandlin had a court-appointed, taxpayer-funded attorney.

Prosecutors said that — “incredibly” — Sandlin had managed to spend more than $13,500 on commissary, canteen, phone calls and Netflix during his time in jail; the judge ordered him to apply the unspent balance to his fine.

Look Ahead America, a nonprofit formed in 2017 by former Trump campaign staffer Matt Braynard to “register and educate and enfranchise disaffected citizens” saw its contributions jump to $793,000 in 2021 from an average of $25,000 in previous years, Braynard said.

Along with voter registration efforts, Look Ahead America has taken a prominent role in supporting the Jan. 6 defendants, promoting a nationwide program of vigils, maintaining a database of court cases and launching a job board to link Jan. Sixers with sympathetic employers (application question: “How has the persecution of Jan. 6 affected you?”).

In an interview, Braynard defended programming such as the job board.

“A lot of these folks — love them or hate them, heroes or not — have served their time and they’re getting out of prison now with two strikes against them — they’ve served time and they’re a J6er,” he said. “It’s really difficult.”

Several defendants charged in the Jan. 6 attack are being held at the D.C. Central Detention Facility. (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

Braynard said that the organization has never solicited money to give to the defendants directly but hosts them on its podcast about their experience, “Political Prisoners.” The funds, he said, were spent predominantly on salaries or a voter registration effort and buses and security for three “Justice for J6” rallies in Washington.

Paula Calloway, a real estate agent with a family welding business in King, N.C., has spent the past two years organizing a mail drive for prisoners called the “Patriot Mail Project,” using her own money for postage to forward mail to prisoners in jail.

This Christmas, she said, she received $56,000 in donations that she then passed on to 30 prisoners’ families. She said she planned to post a detailed online accounting of how the money was disbursed.

“Honestly we never dreamed it was going to do so well,” she said. “The fact that this is going on here in this country, it pulls at you. The more you learn about them, you realize these people could be like my family. The similarities are mind-blowing.”

Calloway attended Trump’s Jan. 6 rally near the White House and made it to the Capitol before the big crowd arrived.

She dismissed facts recounted by those investigating and judges meting out Jan. 6 convictions by saying, “They were not there and have no idea what they are talking about. There’s more to it. I believe there were some there to instigate.”

The prayer call goes live every night at 9 p.m. Eastern on a Telegram channel devoted to supporting the Jan. 6 “hostages” called “The Prisoner’s Record.” It is run by David Clements, a former New Mexico State University business professor who has made a national career as a disseminator of election disinformation.

Clements wrote in the channel recently that his volunteers send “12K directly to hostages to fund their prisoner commissaries, phone accounts and write letters to keep the human connection. Please join us this month as we complete another round of sending tangible love.” Clements did not respond to an email requesting details on how the money is accounted for.

David Clements, a former New Mexico State University professor, recites the Pledge of Allegiance on Thursday at a demonstration outside a D.C. jail. (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

On the night those on the channel prayed for the prisoners to find unity in the cells, they also listened to a tape of a choir singing “The Lord’s Prayer” and read aloud a letter that Jake Lang wrote from jail that’s been anthologized with other prisoners’ missives, sketches and notes and compiled in a glossy coffee table book. Called “The American Gulag Chronicles — Letters from Prison,” it sells for $45 online, with proceeds going to prisoners’ legal funds.

Lang, 27, a former high school wrestler from Narrowsburg, N.Y., has had a contentious time since he was arrested in 2021.

While in various jails, he’s gone on hunger strikes, tried to draw attention to what he sees as inhumane treatment of prisoners through tweets and blog posts and irked authorities by abusing the attorney telephone lines to do podcasts. He’s been transferred 11 times, which officials said was because they had received threatening communications as a result of his advocacy.

“It’s hard to run all the different organizations and websites that I’m running for the J-Sixers from here but I’m managing by the grace of God,” he said in a telephone interview with Trump lawyer Christina Bobb on Dec. 13 that was posted on his Instagram account.

Both he and his father have argued that he was protecting other protesters from police brutality. Ned Lang, who owns one of the biggest sludge-processing facilities in New York, has created a documentary he says clears his son’s name and spent more than $100,000 in right-wing media to promote it. The Langs maintain two GiveSendGo accounts that have raised $111,652 and $223,843 respectively.

“We’re just trying to keep the word out, trying to make the American people know there is another side to the story that the mainstream media never tells you,” the elder Lang said.

The Washington Post’s Tom Jackman, Rachel Weiner, Spencer S. Hsu and Monika Mathur contributed to this report.