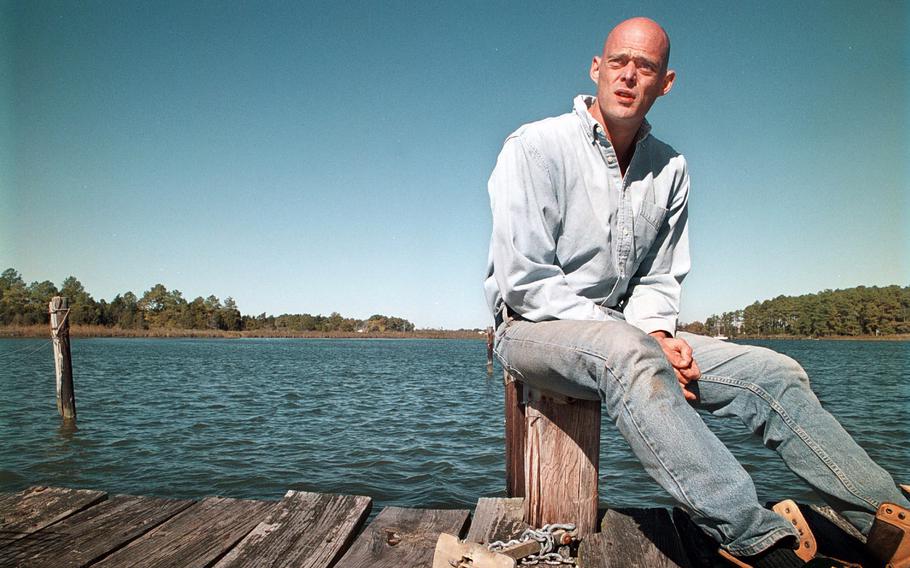

Nate Thayer in Maryland in 2000. Thayer, the last Western journalist to interview the Khmer Rouge's genocidal leader Pol Pot, died at his home in Falmouth, Mass. He was 62 and had been in declining health. His body was found Jan. 3, 2023. (Juana Arias/The Washington Post)

Nate Thayer, an American journalist who chased stories of conflict across the jungles of Southeast Asia and was the last Western correspondent to interview the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal leader Pol Pot, has died at his home in Falmouth, Mass. He was 62.

Robert Thayer said his brother’s body was found Jan. 3, but it was not immediately clear when he died. Thayer wrote last year that he was in declining health, including developing sepsis after foot surgery and was told by doctors he “will never walk again.”

During decades of reporting beginning in the late 1980s, Thayer cultivated a reputation as a freelancer willing to endure hardships and risks to track down far-flung stories for outlets including Soldier of Fortune magazine, the Far Eastern Economic Review, the Associated Press and The Washington Post.

With his shaved head and teeth stained by chewing tobacco, he evoked a throwback-style correspondent image and delighted in regaling others with stories from the field. They included near misses, including suffering serious injuries when the Cambodian guerrilla transport truck he was aboard triggered an antitank mine in October 1989.

In later years, he used social media to relentlessly burnish his hard-charging image and push his claims that he was wronged by ABC’s “Nightline” over rights issues to use video from Pol Pot’s July 1997 kangaroo-court “trial” by disgruntled former followers at a Khmer Rouge camp in northern Cambodia.

His reporting on Pol Pot’s final months remained the journalistic centerpiece of Thayer’s career — a major journalistic coup that drew international attention. His work also added important historical details to the “killing fields” legacy of the Khmer Rouge’s 1975-1979 rule. An estimated 1.7 million Cambodians — intellectuals, doctors, dissidents and many others — lost their lives as the regime attempted to impose a radical agrarian Communist order.

“He illuminated a page of history that would have been lost to the world had he not spent years in the Cambodian jungle,” noted an award bestowed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in 1998.

A year earlier, Thayer convinced members of the surviving Khmer Rouge factions that international coverage was needed for Pol Pot’s reckoning before those former guerrillas who had turned against him. “Crush, crush, crush Pol Pot and his clique,” some chanted as Thayer and a cameraman from Asiaworks Television, David McKaige, reached the remote Anlong Veng camp.

Writing in the Far Eastern Economic Review, Thayer described how Pol Pot was sentenced to life imprisonment and led away to a Toyota Land Cruiser with tinted windows.

“Some people respectfully bowed, as if to royalty,” he wrote. Thayer did not have the chance to ask Pol Pot any questions.

Thayer struck a verbal deal with ABC to allow the video to be broadcast on the ABC News program “Nightline.” During the segment, Thayer described the event as if Adolf Hitler had survived and was found later in a bunker in South America.

“Remember, I’ve lived in Cambodia,” he told “Nightline” host Ted Koppel. “Most of my friends have had their lives destroyed by Pol Pot. So it was a profoundly moving moment. . . . I cried many times for everybody I knew.”

The network said Thayer received $350,000 and was given proper credit. But ABC also contended that Thayer failed to understand that the clips would also be posted on the internet and go into the public domain.

Thayer long insisted that ABC reneged on promises to give him control of the material. He later turned down a Peabody Award for the “Nightline” broadcast, which cited his reporting as “significant and meritorious.”

“I didn’t have a penny a week ago, and if I don’t have a penny a week from now, I still have my integrity,” he was quoted as saying in the American Journalism Review.

Thayer was allowed to return to the camp in October 1997 with a promise to interview Pol Pot. The last Western journalists to do so, in 1978, were The Post’s Elizabeth Becker and Richard Dudman of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Thayer was told to wait near a small hut.

Thayer wrote in the Far Eastern Economic Review about how the former dictator, then 72, needed to grab his arm to walk a short distance to the hut.

“The man who presided over the Cambodian holocaust is about to give his first interview in 18 years,” Thayer wrote. “It’s his chance to make some kind of peace with his bloodstained past.”

Pol Pot appeared incongruously soft-spoken, making his points calmly and in measured tones.

“Were you responsible?” asked Thayer about the mass killings.

“I only made decisions concerning the very important people,” Pol Pot replied. “I didn’t supervise the lower ranks.”

Thayer had one more exclusive concerning Pol Pot: He was back at the Anlong Veng camp a day after Pol Pot died in April 1998 and took photos of the body before it was cremated.

His reporting became the only independent confirmation of Pol Pot’s death. “He’s dead,” Thayer told The Post in a telephone interview at the time. “That was Pol Pot. There was no question that was Pol Pot.”

Yet Thayer found the death more of an open wound than a closure.

“And along with Pol Pot’s death, unfortunately, goes the chance of finding out really what happened and why,” Thayer told NPR’s “All Things Considered.” “There’s so many unanswered questions of why so many people suffered so unspeakably and so unfairly. And this man was in sole control.”

Nathaniel Talbott Thayer was born in Washington on April 21, 1960. His family had deep ties in Southeast Asia through his father, Harry E.T. Thayer, who had served in diplomatic postings in Hong Kong, Taipei and elsewhere before returning to a State Department role. (He was U.S. ambassador to Singapore from 1980 to 1985.)

Thayer’s other major point of reference was the Boston area, where his Brahmin family tree was marked by places such as Harvard’s Thayer Hall.

When asked about his illustrious family pedigree, Thayer wryly pointed to Judge Webster Thayer, who sentenced Italian immigrant anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti to death after their murder convictions in 1921. They were electrocuted in 1927, despite strong evidence of their innocence. Fifty years later, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis (D) said they had been unfairly tried in an era “permeated by prejudice.”

Deploying an epithet, Thayer told the New Yorker that he cited the judge “whenever they call me the black sheep of the family.”

Thayer studied at the University of Massachusetts in Boston but did not graduate. His first work in Southeast Asia was part of 1984 academic research project on refugees from the Khmer Rouge regime before landing freelance assignments for Soldier of Fortune on guerrilla uprisings in Myanmar, then widely known as Burma.

In 1992, Thayer followed the Vietnam War-era Ho Chi Minh Trail and encountered a lost group of the U.S.-allied Montagnard militia that did not know the conflict had been long over. Two years later, Thayer mounted an elephant as part of an expedition to seek a possibly extinct Southeast Asian bovine called a kouprey. They found none.

He described it as a “team of expert jungle trackers, scientists, security troops, elephant mahouts and one of the most motley and ridiculous looking groups of armed journalists in recent memory.”

Thayer was expelled from Cambodia in 1994. He returned and was booted out again for stories that purported to show links between Prime Minister Hun Sen and heroin traffickers.

After a fellowship in international studies at Johns Hopkins University, he and photojournalist Nic Dunlop tracked down a Khmer Rouge torturer, Kang Kek Iev, also known as Brother Duch, who agreed to talk after learning Thayer had interviewed Pol Pot. Duch surrendered to authorities after Thayer’s piece ran in the Far Eastern Economic Review.

Thayer later covered the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq for Slate and did web-based stories on growing white-nationalist movements in the United States.

In addition to his brother, Thayer is survived by his mother, Joan Leclerc of Washington; and two sisters.

Despite his prolific workload, Thayer never managed to put the finishing touches on his memoir, with a proposed title of “Sympathy for the Devil: Living Dangerously in Cambodia.” What pushed him on was personal: his deep empathy for the country and its past horrors under the Khmer Rouge.

Then when he heard in June 1997 that Pol Pot had been imprisoned, Thayer saw a chance for a major professional break. “The last great interview in Asia,” he told the New Yorker.

He eventually returned to the States — first getting a farmhouse in 2000 on the Chesapeake Bay shores in Maryland — but said he could feel more at ease in Cambodia than big American cities such as New York.

“Man, I can’t control my perimeter there,” he said. “It’s the crazies that I can’t deal with.”