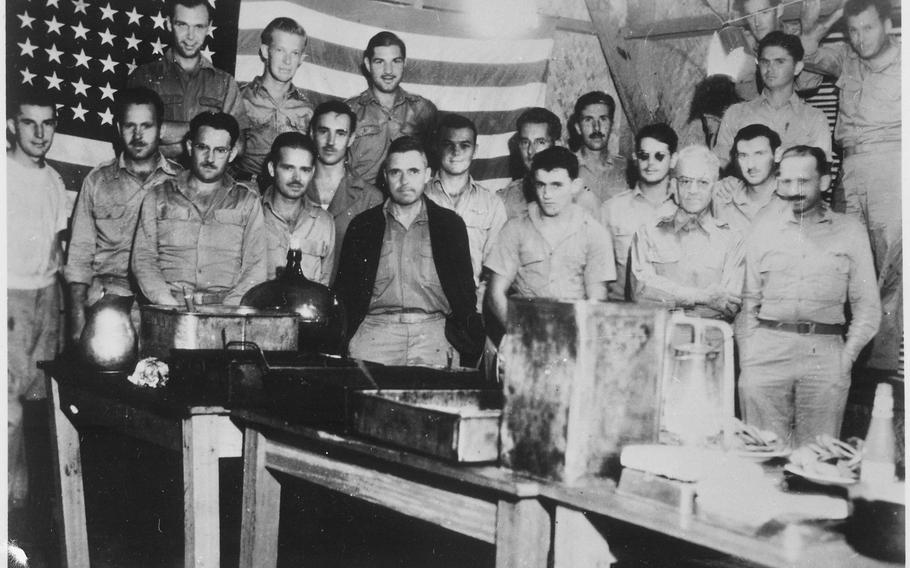

American prisoners of war celebrate the 4th of July in the Japanese prison camp of Casisange in Malaybalay, on Mindanao, Philippine Islands, in 1942. It was against Japanese regulations and discovery would have meant death, but the men celebrated the occasion anyway. (National Archives Catalog, 111-SC-333290)

Descendants of some U.S. troops taken prisoner in the Philippines during World War II have called into question an ongoing effort to award those veterans with Congressional Gold Medals, saying the latest version honors only those who fought in Bataan and Corregidor and excludes other areas of the Philippines and Pacific.

Since 2009, the New Mexico congressional delegation has introduced bills to establish the medal to honor those captured at the Bataan peninsula and on Corregidor Island, two of the main defensive positions that the U.S. established after the Japanese invaded the Philippines within days of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. U.S. and Filipino troops on Bataan surrendered on April 9, 1942, after running out of food and ammunition. Corregidor held out for nearly a month before surrendering.

The current version of the bill honors only those who served on Bataan and Corregidor.

It does not mention the thousands of U.S. troops who were fighting in other parts of the Philippines until the top U.S. commander, Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, surrendered all American and Filipino forces in the Philippines when Corregidor fell. Some members of the 1,000-strong Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society would like to see Americans who resisted Japan’s sweep through the Pacific but were captured at Wake Island, Guam, Java, the Aleutians and at sea honored, too.

Some of them were imprisoned alongside defenders of Bataan and Corregidor when the Japanese consolidated many of their prisoners at camps in Japan and Manchuria as other areas once under their control fell to the advancing Americans and their allies.

“It's very much a misreading of the history of the fall the Philippines. You cannot divorce Bataan and Corregidor from everything else that was going on,” said Mindy Kotler Smith, a member of the memorial society. Her husband’s great uncle Fletcher Wood served in the Philippines with the Army Corps of Engineers and died in Bilibid prison in Manila.

Congress has commissioned gold medals as its “highest expression of national appreciation” since the American Revolution. Other groups to receive the medal for service during World War II include Merrill’s Marauders, a unit that served in the jungles of Burma, women who joined the workforce as a “Rosie the Riveter,” the merchant mariners of World War II and the Navajo Code Talkers.

House and Senate rules state that legislation establishing such a medal must be co-sponsored by two-thirds of the chamber membership to advance to committees. If this doesn’t happen by the end of the year, the legislation must be resubmitted in the next session of Congress.

The latest version of the Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Congressional Gold Medal Act was introduced by Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., in April 2021. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, D-N.M., introduced the companion bill in the House a month later. Both have sat idle because they have bipartisan support but not enough co-sponsors.

“Bataan veterans deserve the recognition of our nation’s highest and most distinguished honor for their perseverance and patriotism. We must never forget their undaunted heroism in the face of unthinkable conditions and horrific abuses,” Heinrich said in a statement.

The Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society was founded in 1946 by survivors of the Philippine campaign as they recovered in a Massachusetts hospital following their liberation from captivity at the end of the war, Smith said. As those men grew old and died, their descendants took over the organization, and now focus on education and preservation of this specific chapter of World War II history.

They’ve watched over the years as lawmakers from New Mexico have introduced the different bills to honor their sacrifice and have offered their own guidance on how to better honor the estimated 27,000 American service members held prisoner by the Japanese during World War II. About 12,000 of them died in captivity, according to the memorial society.

They included up to 700 Americans and several thousand Filipinos who died of beatings, beheadings, starvation and lack of water during a 5- to 10-day forced march from Bataan to prison camps that became known as the Bataan Death March. Thousands more perished in the camps.

However, determining who should be honored by a congressional medal has proven a challenge.

Among those who surrendered at Corregidor were 77 Army and Navy nurses, all of whom were liberated when the U.S. recaptured the Philippines late in the war. The memorial society fears the current bill would exclude them because the current wording refers to “troops.”

The first legislation to award medals in honor of POWs in the Philippines dates to 2009, when Heinrich served in the House. He proposed the medal to be presented to defenders of Bataan, Corregidor and the main Philippine island of Luzon. It did not mention any specific units nor Americans taken prisoner in the central and southern Philippines.

That same year, former Sen. Tom Udall, also a New Mexico Democrat, introduced the companion bill in the Senate, but with a more narrow focus. It only authorized medals for those who were taken prisoner at Bataan but not Corregidor or other locations overrun by the Japanese.

Heinrich’s office did not respond to queries about whether he would consider changes to the legislation in the next congressional session.

“It is our hope that they will amend and modify the bill so that we can support it,” said Jan Thompson, president of the memorial society whose father, Navy pharmacist’s mate Robert E. Thompson, surrendered on the island of Corregidor. “We’re not comfortable supporting it as it is, and we’d like to be able to support.”