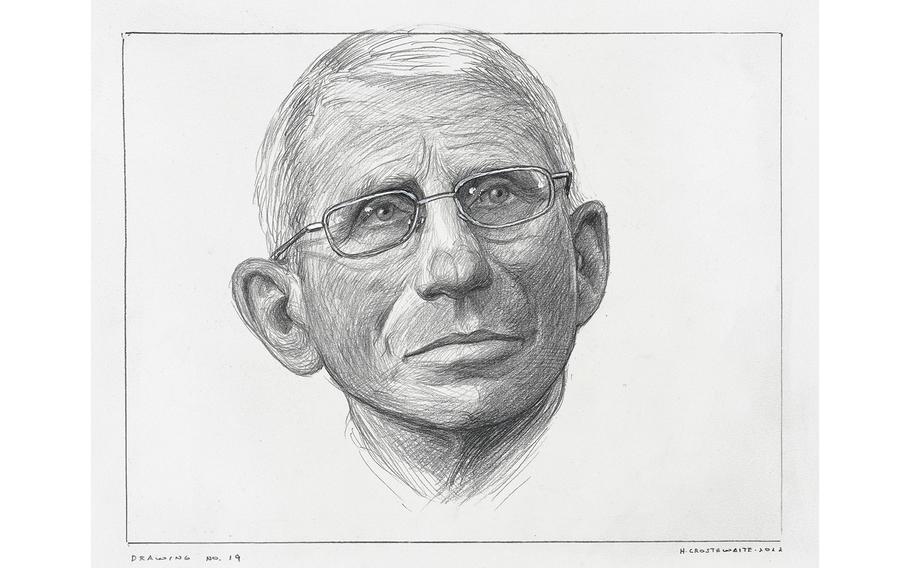

Artist Hugo Crosthwaite created a five-minute stop-motion drawing animation featuring Anthony S. Fauci. It will be shown in D.C.’s National Portrait Gallery. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Acquired through the generosity of Anonymous; Michael Hollander; Walter and Patricia Moore)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

WASHINGTON — Anthony Fauci doesn't know how history will remember him, but he does know how it will see him.

On a recent Saturday, he's inside a private room at Washington's National Portrait Gallery, looking at the work of art that will hang alongside presidents, celebrities, inventors and other distinguished Americans. It's a video - a stop-motion animation - chronicling his landmark career through a series of intense drawings that leap out from the screen.

"I don't think of myself in the same category as the people in the National Portrait Gallery, even if other people do," says the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who became the face of the pandemic, for better and worse. "You never quite see yourself at that level."

Fauci has been photographed too many times to count, and people have sent him dozens of paintings - notably singer-artist Joan Baez, who called him up and said, "I've admired what you've done. I have a portrait of you." The two became friends; Fauci was her date when Baez received the Kennedy Center Honors last year.

"You always think things don't do justice to you until you realize that maybe your own image of yourself is a little bit distorted compared to what the world sees," he says. In Fauci's mind, he's far more human than he's often depicted: "I don't take that kind of personal vanity stuff seriously. Brad Pitt played me on 'Saturday Night Live.' I know I'm not Brad Pitt, no matter how much I would love to look like Brad Pitt."

The gallery's portrait is a decidedly modern take on the genre: Artist Hugo Crosthwaite made graphite and charcoal drawings and adapted them into the animated video, which will go on exhibit Nov. 10, part of the gallery's Portrait of a Nation awards. (Other honorees include José Andrés, Clive Davis, Ava DuVernay, Marian Wright Edelman, and Serena and Venus Williams.)

A successful pairing of subject and artist is a feat of creative matchmaking; as much about chemistry as artistry. The gallery curators thought that Crosthwaite, winner of its 2019 portrait competition, would be an intriguing complement to Fauci.

“It’s a very poignant feeling,” says Anthony Fauci of watching Hugo Crosthwaite’s video. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Acquired through the generosity of Anonymous; Michael Hollander; Walter and Patricia Moore)

"They said, 'You're not going to believe it, but we have somebody for you who is one of our real stars,' " remembers Fauci. "And then they said, 'But he's very unusual.' And I said, 'Fine. I don't know what that means, but that sounds interesting.' "

Crosthwaite recalls, "They proposed Fauci and I almost fell out of my seat. Yes, yes, definitely yes!"

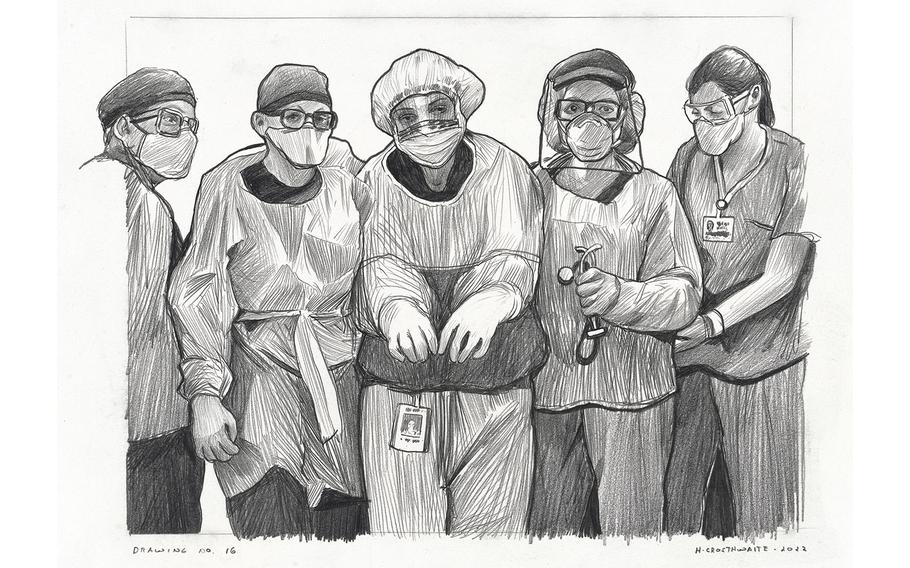

The process began more than a year ago with an hour-long interview at Fauci's kitchen table, where the artist quizzed him about his career. Then he went back to his Mexican home, where he created 19 black-and-white images depicting the two historical bookends of Fauci's life: his role in the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and the pandemic of 2020.

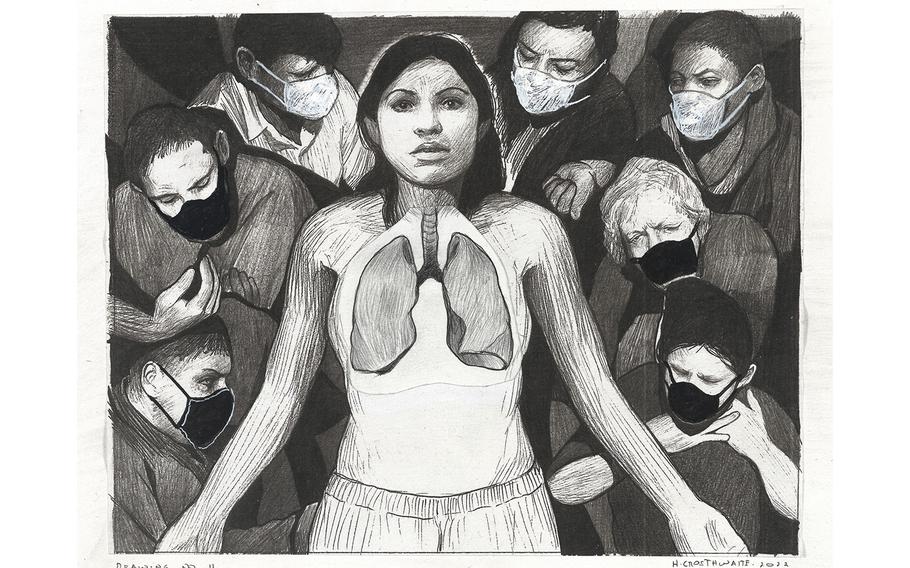

Crosthwaite, whose works are laced with social issues, says he wanted to capture not just the man, but the era. He knew he wanted to do a stop-motion animation based on those drawings; the trick was how to squeeze everything into a five-minute video.

In that private room at the gallery, surrounded by classic portraits of first ladies Hillary Clinton and Laura Bush, Fauci watches the final video, which will run on a loop surrounded by seven of the drawings.

"The pace of the music right away attracts you because it is commensurate with how he sketches," narrates Fauci. There's the National Institutes of Health building where he's based, his lab, his co-workers - then victims of HIV, and the demand from AIDS activists that Fauci and the government do more.

The action fast-forwards to a new virus - the coronavirus - attacking the lungs of a woman who dies. "Here's me at the White House now with my famous palm to my head when the president [Trump] said something completely ridiculous," he points out. And then images of protesters against vaccines and masks.

Hugo Crosthwaite’s portrait of Fauci depicts scenes from the AIDS crisis and the coronavirus pandemic. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Acquired through the generosity of Anonymous; Michael Hollander; Walter and Patricia Moore)

Now a sketch of Fauci's face - serious, pensive: "Here I am, getting a bit older. You notice my eyes?" It's the first thing you notice; he looks infinitely sad.

This portrait is as much about suffering and death as it is about Fauci. What stands out for him is the differences between the vocal protesters of the two eras: The activists of Act Up, a movement to bring more attention to the AIDS crisis, were trying to cure a disease, unlike anti-vaccine activists, who Fauci says were anti-reality and anti-common sense.

He respected and became close friends with those activists from the 1980s - and remains so today. "They were good people and there was no way they were going to hurt me," he says. "So I didn't need the protection that I have now with the people who really want to hurt me."

Fauci has no problem explaining that journey, but has a harder time articulating how it feels. "You remember yourself when you were quite young in the beginning, and then you see what you went through - and then you're still kind of living through what's going on right now with covid. So it's a very poignant feeling."

Not proud?

"No, it's poignant," he says. "Proud is a funny word because it can be taken out of context. I am proud of the things we've done. But what Hugo did was to show, in a very interesting, subtle way, how complicated it all was."

He hopes that visitors to the gallery in, say, 50 years - people who never heard of him - might get curious: "Maybe somebody wanting to explore that history a little bit more deeply, because those are really two very historical events that have occurred within the single lifetime of us. Not just me, but of our generation."