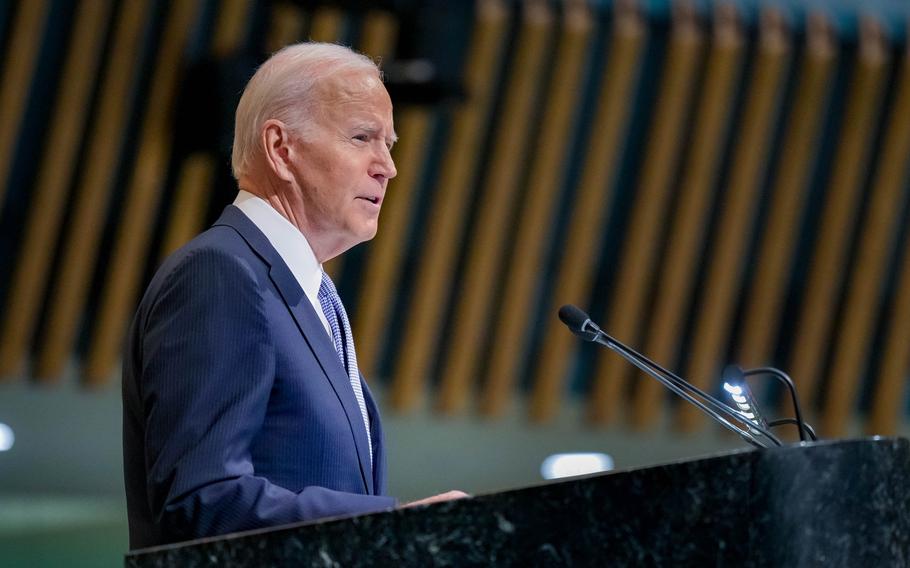

President Biden speaking at the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly on September 21, 2022. The United States for several months has been sending private communications to Moscow warning Russia’s leadership of the grave consequences that would follow the use of a nuclear weapon, according to U.S. officials. (Twitter)

The United States for several months has been sending private communications to Moscow warning Russia’s leadership of the grave consequences that would follow the use of a nuclear weapon, according to U.S. officials, who said the messages underscore what President Joe Biden and his aides have articulated publicly.

The Biden administration generally has decided to keep warnings about the consequences of a nuclear strike deliberately vague, so the Kremlin worries about how Washington might respond, the officials said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to describe sensitive deliberations.

The attempt by the White House to cultivate what’s known in the nuclear deterrence world as “strategic ambiguity” comes as Russia continues to escalate its rhetoric about possible nuclear weapons use amid a domestic mobilization aimed at stanching Russian military losses in eastern Ukraine.

The State Department has been involved in the private communications with Moscow, but officials would not say who delivered the messages or the scope of their content. It was not clear whether the United States had sent any new private messages in the hours since Russian President Vladimir Putin issued his latest veiled nuclear threat during a speech announcing a partial mobilization early Wednesday, but a senior U.S. official said the communication has been happening consistently over recent months.

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, wrote Thursday in a post on Telegram that territory in eastern Ukraine would be “accepted into Russia” after the completion of staged “referendums” and vowed to strengthen the security of those areas.

To defend that annexed land, Medvedev said, Russia is able to use not only its newly mobilized forces, but also “any Russian weapon, including strategic nuclear ones and those using new principles,” a reference to hypersonic weapons.

“Russia has chosen its path,” Medvedev added. “There is no way back.”

The comment came a day after Putin suggested Russia would annex occupied lands in Ukraine’s south and east, and incorporate the regions formally into what Moscow considers its territory. He said he was not bluffing when he vowed to use all means at Russia’s disposal to defend the country’s territorial integrity — a veiled reference to the country’s nuclear arsenal.

Biden administration officials have emphasized that this isn’t the first time the Russian leadership has threatened to use nuclear weapons since the start of the war on Feb. 24, and have said there is no indication Russia is moving its nuclear weapons in preparation for an imminent strike.

Still, the recent statements from the Russian leadership are more specific than previous comments and come at a time when Russia is reeling on the battlefield from a U.S.-backed Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Whereas previous Kremlin statements appeared to be aimed at warning the United States and its allies against going too far in helping Ukraine, Putin’s most recent comments suggested Russia is considering using a nuclear weapon on the battlefield in Ukraine to freeze gains and force Kyiv and its backers into submission, said Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, a nonproliferation advocacy group in Washington.

“What everyone needs to recognize is that this is one of, if not the most, severe episodes in which nuclear weapons might be used in decades,” Kimball said. “The consequences of even a so-called ‘limited nuclear war’ would be absolutely catastrophic.”

For years, U.S. nuclear experts have worried that Russia might use smaller tactical nuclear weapons, sometimes referred to as “battlefield nukes,” to end a conventional war favorably on its terms — a strategy sometimes described as “escalate to de-escalate.”

On Thursday, Vadym Skibitskyi, deputy head of Ukrainian military intelligence, told the U.K.’s ITV News that it is possible Russia will use nuclear weapons against Ukraine “to stop our offensive activity and to destroy our state.”

“This is a threat for other countries,” Skibitskyi said. “The blast of a tactical nuclear weapon will have an impact not only in Ukraine but the Black Sea region.”

The Ukrainians have tried to signal that even a Russian nuclear strike wouldn’t force them into capitulation — and in fact could have the opposite effect.

“Threatening with nuclear weapons . . . to Ukrainians?” Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, tweeted on Wednesday. “Putin have not yet understood who he is dealing with.”

In an interview with CBS News’s “60 Minutes” that aired Sunday, Biden was asked what he would tell Putin if the Russian leader is considering using nuclear weapons in the conflict against Ukraine.

“Don’t. Don’t. Don’t,” Biden said. “You will change the face of war unlike anything since World War II.”

Biden declined to detail how the United States would respond, saying only that the reaction would be “consequential” and would depend “on the extent of what they do.”

The Biden administration would face a crisis if Russia were to use a small nuclear weapon in Ukraine, which isn’t a U.S. treaty ally. Any direct military U.S. response against Russia would risk the possibility of a wider war between nuclear-armed superpowers — the avoidance of which the Biden administration has made its No. 1 priority in all of its Ukraine policymaking.

Matthew Kroenig, a professor of government at Georgetown University and director of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council, has argued that the best option for the administration, if faced with a limited Russian nuclear strike in Ukraine, might be to step up backing for Ukraine and conduct a limited conventional strike on the Russian forces or bases that launched the attack.

“If it’s Russian forces in Ukraine that launched the nuclear attack, the United States could strike directly against those forces,” Kroenig said. “It would be calibrated to send a message that this is not a major war coming, this is a limited strike. If you are Putin, what do you do in response? I don’t think you immediately say let’s launch all the nukes at the United States.”

But even a limited conventional strike by the U.S. military against Russia would be viewed as reckless by many in Washington, who would argue against risking a full-scale war with a nuclear-armed Russia.

James M. Acton, co-director of the nuclear policy program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said it doesn’t make sense at this point to game out U.S. responses because there is such a wide range of possible Russian actions — from an underground nuclear test that doesn’t hurt anyone to a large-scale explosion that kills tens of thousands of civilians — and there are no signs Putin is close to crossing the threshold.

“If he was really thinking very seriously about using nuclear weapons very imminently, he almost certainly would want us to know that,” Acton said. “He would much rather threaten nuclear use and have us make concessions than actually have to go down the path of nuclear use.”

U.S. officials have been stepping up efforts at the U.N. General Assembly this week to deter Russia from seriously considering what would be the first use of a nuclear weapon in a conflict since the atomic bombings of Japan by the United States in 1945.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, speaking at a U.N. Security Council meeting Thursday, said Russia’s “reckless nuclear threats must stop immediately.”

“This week, President Putin said that Russia would not hesitate to use and I quote, ‘all weapons systems available’ in response to a threat to his territorial integrity — a threat that is all the more menacing given Russians’ intention to annex large swaths of Ukraine in the days ahead,” Blinken said. “When that’s complete, we can expect President Putin will claim any Ukrainian effort to liberate this land as an attack on so-called Russian territory.”

Blinken noted that Russia in January joined other permanent members of the Security Council in signing a joint statement declaring “nuclear war can never be won, and must never be fought.”

Hudson reported from the United Nations in New York.