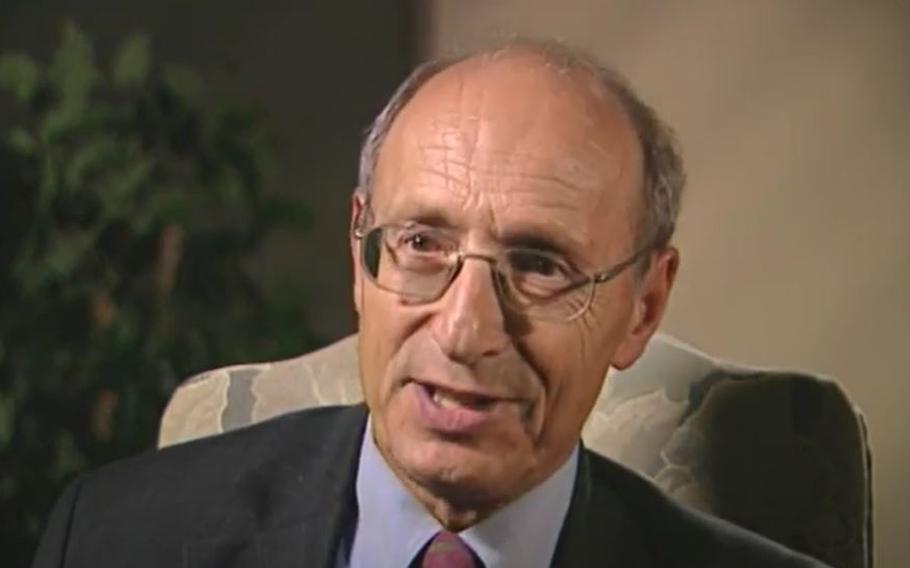

Earl Silbert during an interview in 2008 as part of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Oral History Program. (Screen capture from YouTube)

Earl J. Silbert was in bed when the telephone rang early in the morning of June 17, 1972, rousing him from his sleep.

A colleague was on the other end of the line, calling to inform Mr. Silbert, then the principal assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, of the strange events that had transpired hours earlier at the Watergate complex on the banks of the Potomac River. Five men wearing business suits had been arrested in an attempt to bug the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. One of them was James W. McCord Jr., the security chief for President Richard M. Nixon’s reelection campaign and a former CIA employee.

“It was going to be a hot case,” Mr. Silbert recalled years later. “The only thing open was how hot was hot going to be.”

By his own account, Mr. Silbert did not immediately grasp the case’s magnitude when, as the first prosecutor in the matter of the Watergate affair, he set out to obtain indictments of the five burglars and two key co-conspirators, former White House aides G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt. He said he regarded the break-in as too clumsy to be the work of anyone but underlings, and too foolish to have been approved by anyone of real power.

“You always assume — and maybe that was a mistake — an underlying rationality,” he told the New York Times in 1975.

In the two years after the Watergate burglary, the investigation started by Mr. Silbert and carried forward by special prosecutors, inquiries by congressional panels and reporting by newspapers including The Washington Post revealed a pattern of corruption and coverup reaching deep into the White House. On Aug. 9, 1974, confronted by overwhelming evidence of his role in the wrongdoing, Nixon became the first U.S. president in history to resign.

Mr. Silbert died Sept. 6 at a hospital in Keene, N.H., his family said. He was 86 and had suffered an aortic dissection. After Watergate, he served for five years as U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia and later established a private practice in Washington. But he remained forever associated with the case that began that summer morning in 1972, when he was a 36-year-old federal prosecutor known for his polished manner as “Earl the Pearl.”

During the Watergate prosecution and in the years since, Mr. Silbert’s critics have argued that he fell severely short by leading an investigation that focused narrowly on Liddy, Hunt and the burglars — known as the Watergate Seven — instead of pursuing higher-ranking Nixon associates who eventually went to prison for their role in the Watergate affair. They included, among others, former attorney general John N. Mitchell, former White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman and former domestic affairs adviser John D. Ehrlichman.

Defenders of Mr. Silbert insist that his goal was to conduct the prosecution in an apolitical manner and that he performed ably under impossible conditions — including the interference of acting FBI director L. Patrick Gray III, who thwarted the Watergate investigation by furnishing information about the inquiry to John W. Dean III, the Nixon White House counsel who later pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice.

Mr. Silbert worked on the Watergate prosecutions with two co-counsels, Seymour Glanzer and Donald E. Campbell, as well as investigators including FBI agent Angelo J. Lano. They obtained indictments of the Watergate Seven in September 1972 and won convictions in January 1973 of McCord and Liddy, whom Mr. Silbert had identified as “the man in charge” of the burglary.

Hunt and four burglars, Bernard L. Barker, Frank A. Sturgis, Eugenio R. Martinez and Virgilio R. Gonzalez, all pleaded guilty. McCord later helped blow open the Watergate investigation by asserting in a letter to the judge in the Watergate case, John J. Sirica, and in testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee that perjury had occurred in the trial and that he had been told White House officials including Mitchell and Dean were complicit in the Watergate bugging scheme.

During the trial, Sirica, plainly dissatisfied, had discarded traditional judicial restraint by expressing his incredulity at witness testimony, questioning witnesses from the bench and pushing prosecutors to pursue the case more aggressively.

Mr. Silbert said his strategy was to first obtain indictments of the burglars and their immediate supervisors. Those indictments — and the convictions, plea deals and immunity to follow - would help investigators close in on higher-ranking conspirators.

“There is an unwritten rule in the Justice Department,” he told Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who recorded his remarks in their 1974 book “All the President’s Men.” “The higher up you go, the more you have to have them by the balls.”

Amid mounting evidence of a coverup and growing impatience on Capitol Hill about the speed and scope of the investigation, Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson appointed special prosecutor Archibald Cox to assume authority for the Watergate investigation in May 1973. Cox was fired in the Saturday Night Massacre that October and was succeeded by Leon Jaworski.

In his 2022 book “Watergate: A New History,” journalist and historian Garrett M. Graff wrote that Mr. Silbert and his two co-counsels regarded the appointment of the special prosecutor “as an insult — and too late to be of any help.”

Glanzer died in 2018. Campbell, the surviving co-counsel, told The Post after Mr. Silbert’s death that “everything Earl did was to perfection.”

“His whole goal was we follow the evidence and we go from there,” Campbell said. Meanwhile, Lano recalled, “we were getting lies from everyone.”

Asked about his handling of the Watergate investigation, Graff said in an interview that “I think to this day we don’t have a good sense of what kinds of internal pressures Earl Silbert was under,” and to what degree any shortcomings of the prosecution were due to his “not wanting to know the answers versus being told not to find the answers.”

“I think it is inescapable,” Graff also observed, “that Earl Silbert failed to answer any of the hard questions of the Watergate conspiracy at the time the case was in his control.”

Mr. Silbert became interim U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia in January 1974 and was later officially nominated for the post by Nixon. The nomination encountered resistance in the Senate, where Mr. Silbert was asked to defend the Watergate prosecution. He was renominated twice by President Gerald Ford, Nixon’s successor, before his ultimate confirmation — after a wait of nearly two years — in October 1975.

Mr. Silbert’s champions during the confirmation process included members of the Washington bar and judges of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia — as well as Cox and Jaworski.

“There are points on which my judgment might have varied from yours,” Cox had written to Mr. Silbert and his colleagues when they stepped down from the Watergate prosecution. But “thus far in the investigation,” Cox continued, “none of us has seen anything to show that you did not pursue your professional duties according to your honest judgment and in complete good faith.”

Earl Judah Silbert was born in Boston on March 8, 1936, and grew up nearby in Brookline. His mother was a social worker and homemaker. His father, a lawyer, had served briefly as a Republican member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. The younger Mr. Silbert was a Democrat.

After graduating in 1953 from the private Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, Mr. Silbert enrolled at Harvard University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in history in 1957 and a law degree in 1960. He began his legal career in the Justice Department’s tax division and worked in private practice after stepping down as U.S. attorney in 1979. His clients included Kenneth L. Lay, the Enron founder who was convicted in 2006 on conspiracy and fraud charges related to the energy firm’s collapse.

Mr. Silbert’s survivors include his wife of 52 years, the former Patricia Allott of Chevy Chase, Md.; two daughters, Leslie Silbert of New York City and Sarah Silbert of Randolph, Vt.; a sister; and three grandchildren.

In recent years, Mr. Silbert worked with his daughter Leslie on a forthcoming memoir, “The Missing Watergate Story.” He recalled in the book that the Watergate prosecution made him a lightning rod not only in public, but also at home. His wife, who had worked on the campaign of George S. McGovern, Nixon’s Democratic opponent in the 1972 election, “loathed” Nixon, Mr. Silbert wrote, and “was convinced he was involved from the start.”

“She frequently proclaimed him guilty, and my stock response — ‘Show me the evidence’ — infuriated her,” Mr. Silbert wrote. “I sympathized. Sharing a home with one of the few people in the country who had inside information on the most-talked-about mystery of the day — and revealed none of it — could only have been maddening.”

One evening, he recalled, his wife became so frustrated by his reticence that “she lost all patience and emptied her glass of port onto my legal pad.”

“I couldn’t win anywhere,” Mr. Silbert wrote. “But that was the job.”