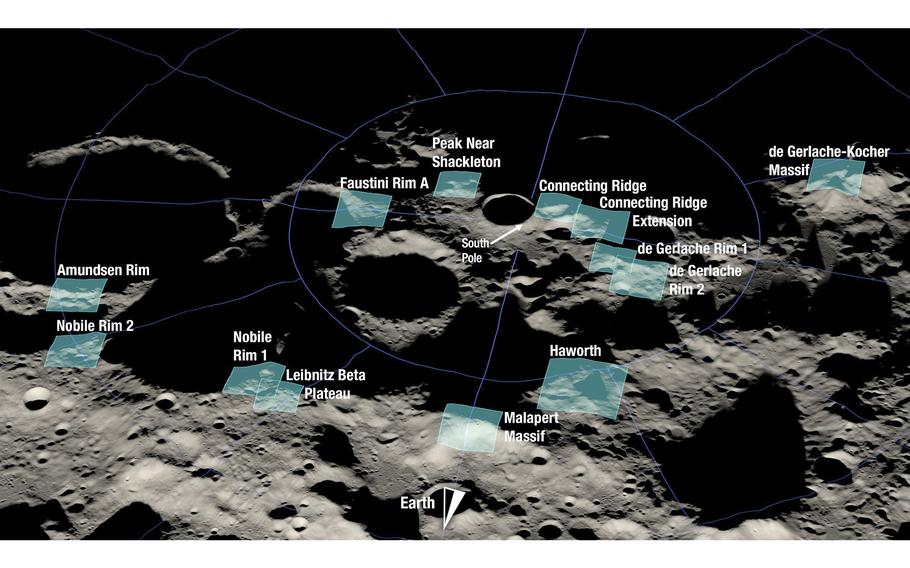

NASA identified the 13 regions at the moon’s south pole where it would like to land astronauts as part of its Artemis program. (NASA)

NASA has yet to launch the rocket that would carry astronauts to the moon, and it hasn't yet selected the crew that would explore the lunar surface as part of its Artemis program. But it has already identified where on the moon the astronauts would land.

The space agency announced Friday that it has selected 13 possible regions at the South Pole of the moon, where there is ice in the permanently shadowed craters, and is a long way from the territory explored by Neil Armstrong and the other Apollo astronauts.

The first human mission to land on the moon in some 50 years is now scheduled for as early as 2025, and would be the first crewed lunar landing since the last of the Apollo missions in 1972. NASA has vowed to return humans to the lunar surface - an audacious plan born during the Trump administration that has been embraced by the Biden White House.

While it has suffered some setbacks and delays, the program is the first deep-space, human exploration program since Apollo to survive subsequent administrations. But unlike Apollo, Artemis is designed to create a permanent presence on and around the moon. And NASA has forged ahead with a sense of urgency, as China also aims to send astronauts to the moon.

In a briefing Friday, NASA officials said they chose the landing sites using data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter - a robotic spacecraft that has been mapping the lunar surface since 2009 - as well as other studies of the moon.

"Selecting these regions means we are one giant leap closer to returning humans to the moon for the first time since Apollo," Mark Kirasich, NASA's deputy associate administrator for the Artemis campaign development division, said in a statement. "When we do, it will be unlike any mission that's come before as astronauts venture into dark areas previously unexplored by humans and lay the groundwork for future long-term stays."

NASA had already announced it was going to return to the lunar South Pole. But the specific sites, all in a cluster of six degrees latitude of the South Pole, were chosen, NASA said, because they provide safe landing spots that are close enough to permanently shadowed regions to allow crew to conduct a moonwalk there as part of their six-and-a-half-day stay on the moon.

That, NASA said, would allow astronauts "to collect samples and conduct scientific analysis in an uncompromised area, yielding important information about the depth, distribution and composition of water ice that was confirmed at the moon's south pole."

Water is important to sustain human life, but also because its component parts - hydrogen and oxygen - can be used for rocket propellant.

The Apollo missions went to the equatorial regions of the moon, where there are long stretches of daylight - for as long as two weeks at a time. The South Pole, by contrast, may only have only a few days of light, making the missions more challenging and limiting the windows of when NASA can launch.

"It's a long way from the Apollo sites," said Sarah Noble, Artemis lunar science lead. "Now we're going somewhere completely different."

The announcement comes as NASA is preparing the first of its Artemis missions, now scheduled for Aug. 29. That flight, known as Artemis I, would mark the first launch of NASA's massive Space Launch System rocket that would send the Orion crew capsule, without any astronauts on board, into orbit around the moon for a 42-day mission.

Earlier this week, the space agency rolled the rocket and spacecraft to pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and officials say everything remains on track for a two-hour launch window that opens at 8:33 a.m. NASA has reserved backup launch dates for Sept. 2 and 5 if there is a delay.

One of the main objectives of the flight is to test Orion's heat shield, Mike Sarafin, NASA's Artemis mission manager, has said. The heat shield is intended to protect Orion and future crew from the extreme temperatures it will encounter when it enters Earth's atmosphere at 24,500 mph, or Mach 32.

The mission would be followed by a flight with four astronauts who would orbit the moon, but not land, as soon as 2024. A human landing, the first since the last of the Apollo missions in 1972, is now tentatively scheduled for 2025.

That mission depends on a number of factors, including the development of SpaceX's Starship rocket and spacecraft, which would rendezvous with Orion in lunar orbit and then ferry astronauts to and from the surface of the moon.

"I feel like we're on a roller coaster that's about to pass the top of the largest hill," Jacob Bleacher, NASA's chief exploration scientist, told reporters Friday. "Buckle up, everyone, we're going for a ride to the moon."