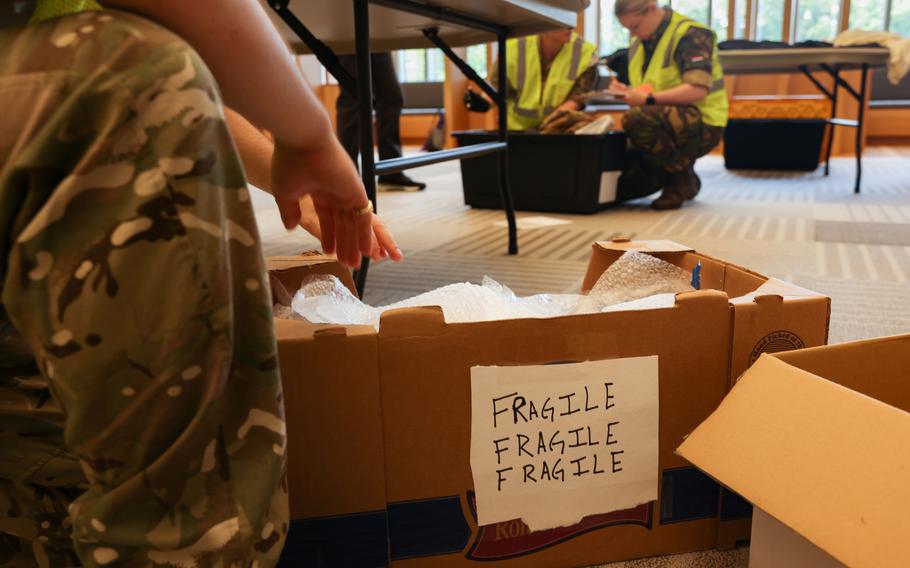

The training drill required participants to inventory, pack and transport pieces of the collection of the fictional Smithsonia Museum. (Maansi Srivastava/The Washington Post)

WASHINGTON - The Smithsonia Museum in the (fictional) country of Pinelandia was about to be attacked by (pretend) enemy forces. Pinelandia’s president asked the cultural heritage specialists at the (also made-up) joint military task force to assist the museum staff in evacuating the museum’s priceless (!) collection.

Wearing neon-yellow vests over their Army combat uniforms, 21 specialists who are actually Army reservists packed up the artifacts (a motley assortment of thrift store vases, paintings and tchotchkes) for transport to a safe location three kilometers away (really at the edge of the museum’s entrance plaza). As the mission progressed, a soldier (not) accidentally stepped through a painting, ripping it from its frame, and the reservists were forced to use pieces of the museum’s (not-so-precious) textile collection when they ran out of protective wrap. Meanwhile, word arrived that (nonexistent) townspeople were alarmed that American soldiers were looting the museum. Work stopped to quell those (imaginary) fears.

For five hours on Wednesday in a large conference room at the National Museum of the U.S. Army in Fort Belvoir, Va., the reservists - who in their civilian lives are archivists, art historians, archaeologists and professors - completed a tense role-playing exercise to train for the evacuation of priceless artifacts from a museum under threat. The drill was the centerpiece of the 10-day Army Monuments Officer Training program, a new partnership between the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative and the U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command that aims to boost the ranks of the Army’s corps of cultural heritage specialists, the modern-day version of the famous World War II Monuments Men. The partnership was formalized in October 2019, and the first session was scheduled for March 2020. The pandemic delayed it until this week.

“The world is falling apart around you. You have to argue for resources, coordinate with other elements of the task force, work with the populace,” said Col. Scott DeJesse, the program director of the Strategic Initiatives Group in Civil Affairs, who led the program with Corine Wegener, the director of the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative. “There is no right answer. You have to speak military language and museum language. It’s an art more than a science.”

Since the training began Aug. 3, the participants have been taught museum operations, risk assessment, collections documentation and the handling, packing, storing and moving of objects. Thursday’s session focuses on salvage - how to recover collections that could not be protected - and working across government agencies and with local partners. The program ends with a graduation ceremony Friday.

“We are looking at the disaster cycle - preparedness, mitigation, response when you have a disaster and the early recovery phase,” Wegener said. “Just like first aid for people, if you don’t have training you freeze. We teach a basic first aid methodology for cultural heritage property ... and the principles of cultural first aid in crisis.”

The 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict requires the military to have specialists on cultural heritage protection to coordinate with civilians in a crisis. The 21 participants in this first training session came from the United States, France, the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, Britain and Lebanon.

“When it comes to talent and knowledge and education, you can’t find a higher level of expertise, knowledge and networks anywhere else in the DOD [Department of Defense],” DeJesse said.

Cultural heritage expertise is especially crucial now, in light of recent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Ukraine. Aggressor forces target cultural heritage sites in their effort to dominate local populations. The command’s objectives are peace and stability, and the destruction of cultural heritage undermines those goals, DeJesse said.

“Culture is a unifier, but culture also causes conflict,” he said. “Conflict in the 21st century is people-centric. You need to understand their hearts and minds.”

The training team included Melissa Weissert, an actual collections manager with the Army’s museums who played an overwrought Smithsonia Museum collections manager, and Paul Morando, the chief curator at the host museum, who played the fictional Smithsonia Museum director. Lt. Col. Brian Lowery delivered an Oscar-worthy performance as the skeptical task force commander.

“I don’t have a lot of confidence in who is going to receive [the artifacts],” he said of evacuating precious antiquities, adding that the team needed to consider all phases of the operation. “Your job won’t be done by moving them to another site.”

“There’s a big difference between hearing about it and doing it. The doing helps reinforce what we learned in the classroom,” Capt. William Baehr, an archivist who lives in Fort Washington, Md., said afterward.

Capt. Sonia Dixon of Omak, Wash., a doctoral candidate in art history, described the exercise as stressful but important. “It helped me think not only about what I can do, but how I will teach others,” she said. “I live in a small town, and if there’s a wildfire, I have experience I could share with the community.”

The afternoon ended with a 45-minute critique by staffers of the real Smithsonian and Army who observed the exercise. They commented on multiple aspects of the drill, including the flow of communication, the division of labor, the inventory numbering system and the soldiers’ packing skills. They offered praise and suggestions for improvement.

The Smithsonian has trained hundreds of museum professionals around the world and has worked with the military in the past. Although the participants will return to their civilian lives around the globe, they have formed a network and will remain connected by the training and supported by Smithsonian resources, Wegener said.

“They know each other’s strengths and skills, and they may in the future be called upon to go on deployments or exercises where they might inject a cultural heritage perspective,” she said. “They are a team, even though they will be separated. That’s rare in the Army Reserve.”