A black mamba, one of the most dangerous snakes in sub-Saharan Africa. Black refers to the inside of the snake's mouth, not its usually gray to dark brown exterior. (Pixabay)

Japan has the habu, the keelback and the mamushi; the United States has the copperhead, sidewinder and Mojave green. Djibouti has the boomslang, the red spitting cobra and the East African carpet viper.

Venomous snakes kill nearly 140,000 people worldwide every year, mostly children and farmers in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization. But their threat may be vanquished if a California doctor’s idea for a snakebite antidote, fostered by a $13.8 million Pentagon contract, proves successful this summer.

Dr. Matthew Lewin, an expert in expedition medicine, found in an existing drug, varespladib, a compact and affordable remedy for snake venom. The Pentagon paid to develop the antidote to shield U.S. troops from an occupational hazard, but it may benefit millions of people with little access to health care.

“It was the furthest thing from my imagination, ever, that the U.S. military would become the champion of this global health effort,” Lewin, of Corte Madera, Calif., told Stars and Stripes by Zoom on May 27. “Obviously friends and family and people put money in along with the military, but I think the real force behind this and the real credibility for the program has come from the military more than anywhere else. And that was not something I expected.”

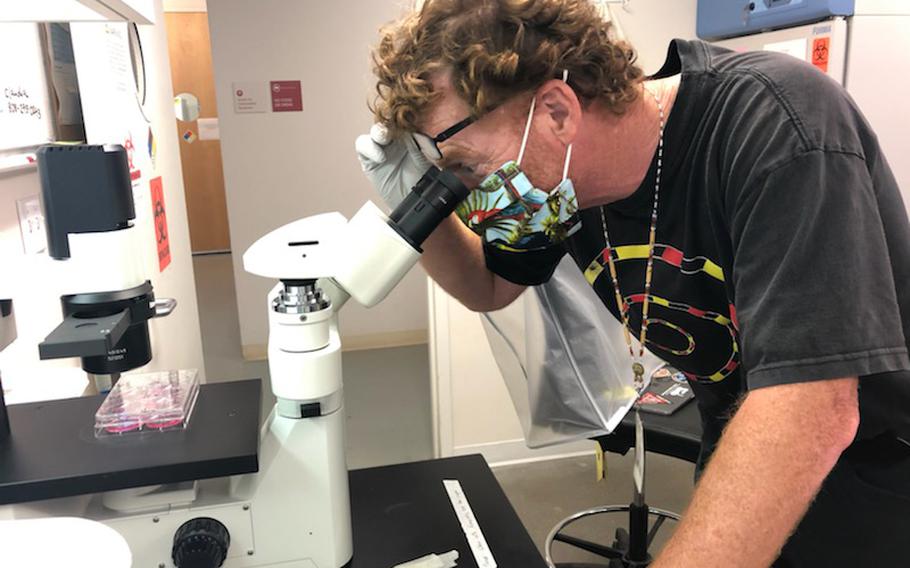

Dr. Matthew Lewin, an expert in expedition medicine, at work at Ophirex Inc. on Nov. 2, 2020. (Sunita Rao/Ophirex Inc.)

Varespladib is in clinical trials with actual snakebite victims in the U.S. and in India, the latter with one of the world’s highest rates of snakebite. If the trials succeed and the Food and Drug Administration approves, the drug could be available by summer 2024.

The trials involve treating 110 people with antivenom and either varespladib or a placebo, then looking for significant improvement in the patients treated with varespladib, according to clincaltrials.gov.

Unlike antivenom, varespladib, a “small molecule,” is available as a pill, requires no refrigeration and counteracts nearly all snake venom.

Antivenom provides an immune response by flooding the body with antibodies that bind with the venom and remove it from the victim’s body. It’s expensive, requires refrigeration and often produces unpleasant side effects.

By contrast, varespladib, developed years ago by pharmaceutical maker Eli Lilly, blocks sPLA2, a basic neurotoxin in venom that causes paralysis, tissue damage and respiratory failure. The drug neutralizes venom in test tubes and stops or reverses its effects in laboratory animals.

Lewin conceived the idea in 2011 and to develop it cofounded Ophirex Inc., a public benefit corporation, the following year with Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Jerry Harrison.

“We are really on the brink of a major revolution of how people think about this,” Harrison, a tech financier, entrepreneur and original member of the band Talking Heads, told Stars and Stripes via Zoom on June 3.

Lewin later found financial and technical support through Lt. Col. Rebecca Carter, a developer of medicines for Air Force Special Operations Command, and Derrick Rossi, a stem cell biologist and cofounder of pharmaceutical company Moderna whose work with messenger RNA led to vaccines for COVID-19.

“Guess what’s a better idea than mRNA for snake bite – a small molecule for snakebite is a better idea,” Rossi said via Zoom on June 4. “I looked at the data, and the data is very, very impressive.”

WHO estimates that venomous snakes bite between 1.8 million and 2.7 million people every year, of whom as many as 138,000 die and another 414,000 are left with serious injuries such as a lost limb. About 75% of snakebite deaths occur because the victim could not get treatment in time.

The Defense Department recorded just 345 nonfatal incidents of snakebite involving active and Reserve members between 2016 and 2020, according to Lindsey Garver, who oversees the snakebite antidote project for Army Medical Materiel Development Activity at Fort Detrick, Md.

However, venomous snakes are a potential hazard where U.S. service members live and work.

In Africa, snakes kill as many as 30,000 people annually, according to Doctors Without Borders. But in 2010, the primary antivenom provider in Africa, the French company Sanofi, curtailed production of its broad-based antivenom Pan Afrique.

That “created a real issue” for U.S. Africa Command and the Defense Health Agency, Garver said by Zoom on May 11. Antivenom was becoming unavailable as special operations increased its exposure to snakes.

“When we talk to our SOCOM user community, what they’re really concerned with is that they’re moving toward small teams, in more austere areas,” Garver said.

A varespladib pill promises to halt or reverse, at the scene, the bleeding, pain and paralysis caused by a snakebite long enough for the victim to get further treatment. It may exceed expectations.

“The drug itself – and we’re still in test and evaluation – it could end up curative,” Garver said. “You still have a wound and a potential for more supportive care, but it may be the only thing you end up needing. The idea is not to leave that person without treatment.”

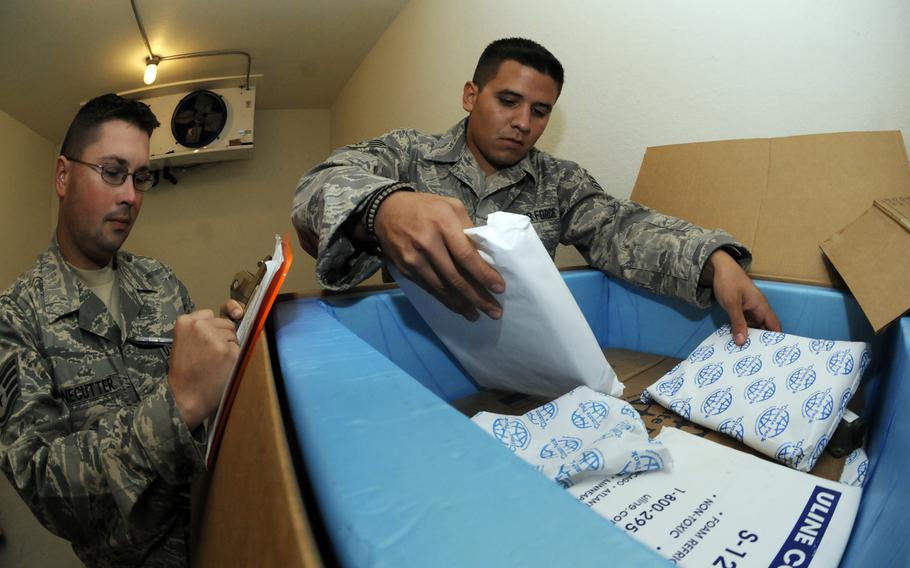

An airman stacks cold bricks on top of medical supplies, includng antivenom, while another logs the re-icing time at an undisclosed location in Southwest Asia in October 2008. (Darnell Cannady/U.S. Air Force)

‘Changing the paradigm’

Varespladib could be the first significant improvement in treating snakebites in 100 years.

The idea came to Lewin in 2011 as he prepared for a research expedition to the Philippines with the California Academy of Sciences. Ten years earlier, herpetologist Joe Slowinski, an academy member, died from a krait bite during an expedition to Myanmar.

“This incident was greatly on my mind, and that is when I started thinking, like, ‘OK, what am I going to do if I don’t have antivenom?’’ Lewin said. “And I was really trying to think deeply about what I could do differently than has already been done.”

A year later, Lewin had himself paralyzed at the University of California, San Francisco, by a colleague, anesthesiologist Dr. Philip Bickler, to prove the concept using another drug as a nasal spray. Lewin recalled feeling panicky as he lay immobilized, but the idea worked.

“I think, from the standpoint of raising funds, nobody could doubt my commitment, to put it lightly,” he said. “It was a pretty scary experience.”

Meanwhile, Carter, a biochemist and director of medical modernization for Air Force special operations, was concerned that Sanofi had stopped making its antivenom.

“That would be a major problem for our special operators in Africa because that was it, right? Antivenom was all we had,” she said via Zoom on June. 7. “We had members that went out on civil affairs, we had members that would treat local people when they needed it, and so we were interested in not just providing a solution for our members just to treat themselves, but also to ensure that they could help others, if needed.”

Subsequently, Carter, on a fellowship at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, in 2016 met Lewin at Venom Week, the North American Society of Toxinology conference. Lewin had missed out on a small DARPA grant and was eager to follow up with Carter, she said.

“He talked to me about his idea, which was totally different,” Carter said. “I think I was one of the first people that he talked to from a technical side that was also really interested in finding a solution to this problem.”

That year, Lewin and his associates showed how varespladib saved rats from lethal venom doses, according to a study in the online National Library of Medicine.

“He was after an antidote, not an antivenom, which was very unique and a different idea, and I felt like this could work,” Carter said.

She found Lewin a $175,000 grant from the Biomedical Research Advisory Group, or BRAG, composed of one representative, herself included, from each of the U.S. military’s special operations commands.

At first, she encountered “a lot” of resistance from the group, Carter said. “Nothing at all against the way they were doing their job, but they were very focused on, as they should be, on other areas of work,” she said.

“They were reluctant to sponsor a new idea for snakebite treatment and they were reluctant to believe that this could work, that a new idea could work,” she said. “Because what we were talking about was completely changing the paradigm.”

With that grant, and money the Air Force later provided, Lewin produced “very convincing” results in further animal studies, Carter said.

Carter retired from the Air Force in 2018 and joined Ophirex, where she is chief development officer.

“I had this idea quite some time ago,” Lewin said, “but she really pioneered this concept for the military.”

Rebecca Carter, left, a doctor of biochemistry and chief development officer for Ophirex Inc., and Lindsey Garver, a doctor of microbiology and immunology and product manager at U.S. Army Medical Materiel Development Activity, photographed on July 22, 2022. (Ophirex Inc.)

Twin missions

Lewin’s idea may have stalled but for a chance meeting in 2012 with Jerry Harrison, formerly a keyboard player and guitarist with defining bands The Modern Lovers and the Talking Heads.

Harrison was the “first reasonable person to listen to me,” Lewin said. “He understood this in a way I didn’t even contemplate because I thought, I’ll publish this and everybody’s going to say, ‘Wow.’”

Friends took Lewin to a party in Harrison’s Bay Area home to raise his spirits. Harrison, looking at the “smart people” assembled in his kitchen, asked: “Does anyone have anything they’ve been thinking about that they have just never have done anything with?”

And Lewin blurted out: “Well, I have this idea about an antidote for snakebites.”

Harrison said he recognized the potential in Lewin’s idea and offered him some practical advice.

“I thought, we’ve got to do this, to save lives, of course,” he said. “Let’s do this.”

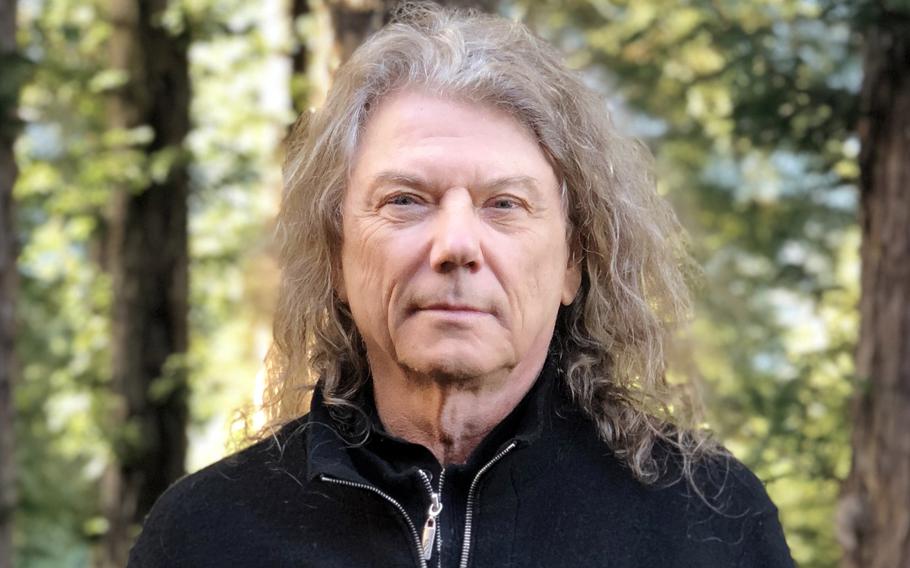

Jerry Harrison, Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, entrepreneur and board member at Ophirex Inc. (Jerry Harrison)

Harrison said he brought to the project lessons he learned as a band member and entrepreneur.

“I said, you need to have patent protection on this, or it’ll just be something that’s entirely taken away from you,” Harrison said. “And I think that was very, very essential.”

Ophirex attracted investors and public and private public grants, including an initial $148,000 from the Defense Health Agency under the Small Business Independent Research program in 2018 and $2.6 million from the Wellcom Trust in 2020.

The visionary mission behind a snakebite antidote doesn’t conflict with the profit motive, Harrison said.

“It’s very important that it is profitable, and particularly significantly profitable for the people who took the risk early on,” he said.

“We need to find a strategy that we basically make enough money in the developed world … probably with government, the country of India’s help, or a nonprofit, that it is affordable to stakeholder farmers in Africa, India, Southeast Asia.”

Pill in the pack

Derrick Rossi confessed a fascination with snakes beginning in childhood.

“I’m a biologist, but I’ve been fascinated with snakes my whole life,” he said. “I’ve known a lot about snakes for a long time.”

His older brother kept snakes, including pythons and boas. His daughters have snakes. “I have four snakes upstairs,” Rossi said from his home.

He had his own serpentine close call.

As a young man paddling a dugout on the Congo River, he rescued a small snake swimming midstream. It crawled up his paddle and flared its hood, announcing itself as a cobra. Rossi’s traveling companion struggled to control the boat, now spinning in the current.

Rossi flung the snake into the river, he said. It slithered back on board and hid among the cargo between the two men.

“So, we had the cobra on board, and we had all our provisions between us, our tents and our food and our pineapples. We started picking through one at a time until finally we caught sight of the snake again,” he said.

He flung it overboard a second time, for good.

Rossi identified it later as a forest cobra. “And by the way, very adept at water, so it was in the water, and it was not stressing in the water,” he said.

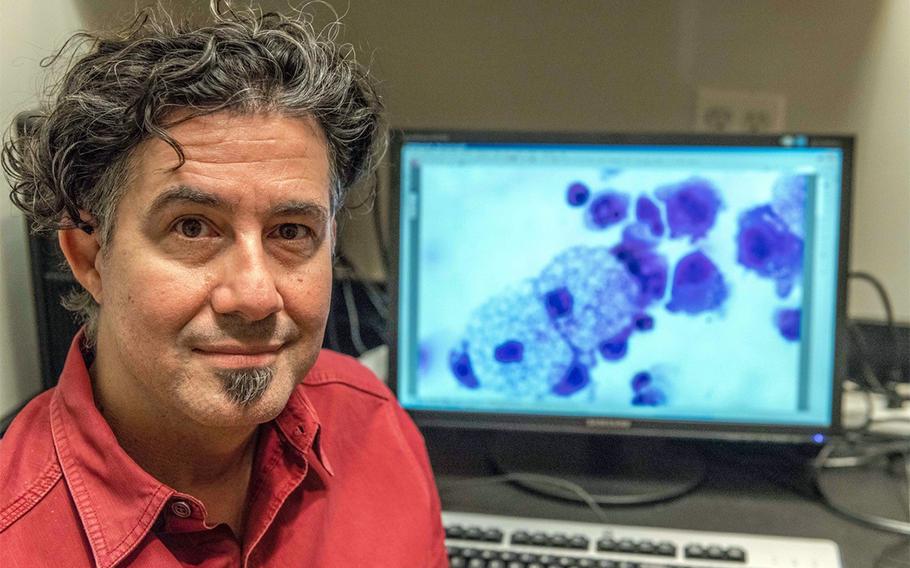

Derrick Rossi, co-founder of Moderna and a board member for Ophirex Inc. (Derrick Rossi)

Rossi saw a possible snakebite vaccine in mRNA but signed on instead as a director with Ophirex after meeting with Lewin. He also raised about $8 million for the company, he said.

“I want to raise awareness,” he said, “and I want to make sure that this medicine, when it gets approved, gets into the hands of the people that need it, as efficiently as possible.”

Varespladib works against a wide variety of snakes and costs less than antivenom and hospitalization, Rossi said.

Every soldier moving into snake country will want the pill in their pack, he said.

“Drugs fail for two reasons: They don’t work and they’re unsafe,” Rossi said. “So, this drug we know is safe, we also happen to know it works.”