Marc and Jane Fogel are seen in a photograph attending a family member’s 2017 wedding in Pennsylvania. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)

OAKMONT, Pa. — The "other American" imprisoned in Russia has a name, too.

He was always just Mr. Fogel to the students he entranced with lectures about the Cold War. But he is Marc Hilliard Fogel on his well-worn passports, abundantly stamped from his many years of teaching International Baccalaureate history courses at schools attended by the children of U.S. diplomats and the global elite in Colombia, Venezuela, Oman, Malaysia and, for the past 10 years, in Russia.

Fogel's charmed life has turned dark at the age of 60. He never sought notoriety. But he and his family slowly have come to the realization that telling the world his name could be his salvation.

For the past 11 months, Fogel has languished in Russian detention centers following his August 2021 arrest for trying to enter the country with about half an ounce of medical marijuana he'd been prescribed in the United States for chronic pain after numerous injuries and surgeries. First he endlessly awaited trial, often in crowded, smoke-choked cells. More recently, he has been serving the first weeks of an incomprehensible 14-year sentence handed down by a Russian judge in June.

Fogel's plight parallels a similar case that has played big on news websites, led cable newscasts and prompted White House pronouncements: the trial of WNBA basketball star Brittney Griner, who also was arrested for attempting to enter Russia with a small amount of medical marijuana. On Wednesday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the United States has made a "substantial proposal" to Russia to secure the release of Griner and another jailed American, Paul Whelan, who is serving a 16-year Russian sentence on spy charges he has denied.

Marc Fogel's wife, Jane Fogel, said in an interview after the news broke that she's still hoping her husband can be included in a swap. But those hopes are fading, she said, speaking publicly for the first time about her husband's case.

"There's a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach that Marc will be left behind," Jane Fogel said Wednesday after the announcement about the possible swap including Griner and Whelan. "It's terrifying. I would hope that President Biden and especially first lady Jill Biden, who is an educator, realize the importance of including Marc in addition to Brittney Griner and Paul Whelan."

In suburban Pittsburgh, Jane Fogel has been watching the Griner case spool out and wondered whether her husband has been forgotten. Griner's wife, Cherelle, received a call from the president. The Fogels have been stalled at the mid-functionary level of the U.S. State Department. Speculation about a possible prisoner swap before Blinken's announcement on Wednesday had earlier trickled into his Russian prison cell, compounding his anxiety.

"That hurt," Marc Fogel wrote in a letter home referencing the prisoner-exchange reports. "Teachers are at least as important as bballers."

In an email reply to an inquiry from The Washington Post, a State Department official said the agency is aware of Fogel's case but did not provide any further information, citing privacy reasons. The official did not respond to interview requests.

After Biden's call with Griner's wife, the White House issued a summary of the conversation saying he told her the U.S. government was working hard to secure the release of Griner and another American and Whelan. Biden added that his administration is pushing for the release of "other" U.S. nationals imprisoned in Russia and other countries. Marc Fogel's name did not appear.

"It seems like the government is working really hard for Brittney Griner and Paul Whelan," Jane Fogel, 60, said in an interview last week at her home, surrounded by mementos of the family's world-wandering. "We want them to work for us, too."

Jane Fogel was quick to point out that she's hopeful Griner and Whelan will also be released. Griner herself has issued a statement pleading for the release of other Americans. It's hard to escape the dread that Fogel's husband's case will never become a priority. That she may never see him again. At times, she said, tearfully, she feels like a "widow."

— — —

Marc Fogel was always the lucky one. No matter the tricky situation, he seemed to land on his feet, like a cat, his friends would say.

Personable, athletic, a little silly sometimes, the Pittsburgh-area native with that big radiant smile, the square jaw, the thick head of wavy hair, could chat up anyone. Things were forever falling into place for him. A madcap idea to hitchhike from Prince George's County, Md., where he was teaching at a public middle school, to see the 1994 Major League Baseball All-Star Game in Pittsburgh led to a chance encounter with his future wife, Jane, a high school friend he'd seen only occasionally since they graduated a decade-and-a-half earlier.

Jane Fogel at home in Oakmont, Pa., with mementos of traveling the world with her husband, Marc. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)

Marc Fogel had a kind of wanderlust that was irresistible. Lying on a beach in Thailand one New Year's Eve in the mid-1990s, he and Jane came up with a plan — they'd get married, have children and teach abroad. Jane told her mother that she'd be back in eight months. It turned out to be 27 years.

They went to places that evoked fear and blank stares among their friends and family. And they gushed about them. The country house surrounded by flowers where they lived outside Medellín, Colombia; the home at the beach in Oman where their eldest son learned to snorkel. An exception was Caracas, Venezuela, where a neighbor was murdered and a student's father was seriously injured in a shooting. Their movements became so limited because of safety concerns that their sons, Sam and Ethan, staged what they jokingly call "a coup" to get the family to move.

Former students remember Marc as an upbeat presence in their lives, who was always saying, "'It's a great day to be alive!' He encouraged the students to also live life, not just ponder it," said Jukka Haapakoski, a student of Marc's in Kuala Lumpur in the 1990s who is now CEO of a Finnish organization that advocates on behalf of unemployed people.

In 2012, after leaving Caracas, the Fogels landed jobs at the Anglo-American School in Moscow, a prestigious $34,000-a-year, pre-K-12 institution that had been established by the U.S., Canadian and British embassies. Their salaries were far beyond anything they could make teaching in the United States. They had an apartment on a vibrant Moscow street. They loved the place. They bopped around Europe visiting friends on school breaks.

They mingled with the embassy crowd and taught their kids. Michael McFaul, a Stanford University professor who was U.S. ambassador to Russia for part of the Fogels' tenure in Moscow, said his son was captivated by Marc's infectious teaching style.

"Mr. Fogel, as he called him, made him excited about these issues in a way that he'd never been before, despite having met [President] Barack Obama and all kinds of fancy people," McFaul said.

In the past few years, as tensions between the United States and Russia grew, it became harder for the Fogels to persuade family and friends that they were in some kind of schoolteacher paradise.

"I would say, 'What are you doing there? Putin is a monster,'" Marc's sister, Elise Hyland, said. Her brother always responded by saying Russians are "lovely people," and that "you have to understand their culture to understand what's happening now," Hyland recalled.

Looking through photos recently, Jane Fogel showed one of her and Marc with friends at their wedding in Malaysia. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)

Marc was careful to avoid any impression that he was taking political positions, said his friend and fellow teacher, Steve Coffey. Sometimes they would change lunch plans just to avoid neighborhoods where demonstrations might be happening.

All the while, Marc's body was falling apart. He'd had surgeries on his back and shoulder, and a knee replacement. The pain was never-ending. He walked with a pronounced limp. Coffey remembers his friend's signature farewell after a long day: "All right, buddy, I'm going to go hit the bath."

Marc was adamant about not taking opioids. In 2021, a doctor recommended he try medical marijuana. It not only helped with the pain — he liked it in the same way someone else might like a glass of wine or a beer.

While home in Pennsylvania for the summer break in 2021, Marc and Jane had to decide whether they'd go back to Russia. Jane was hesitant to return, but her husband talked her into it. Just one more year. Then he would retire, and they could live in their snug Oakmont house with the big oak tree out back and the bay window overlooking the lawn. They could host barbecues. They could make new friends in their neighborhood.

After three decades abroad, a "normal" life, as she put it, sounded "exotic."

— — —

On Aug. 14, 2021, the Fogels landed at Sheremetyevo airport in Moscow after the long flight from New York on the Russian airline Aeroflot. When they deplaned, Jane noticed they were in a different terminal than usual with more security, a change from the lax environment they'd encountered in previous years. She stopped at the restroom and her husband went ahead to the security checkpoint.

When she caught up with him, she could tell something was wrong. His breath had quickened so much that his mask was inflating and deflating like a balloon.

"Jane," he said, "I'm really in trouble."

He'd packed 14 vape cartridges of medical marijuana into his suitcase, stuffing some in his shoes, and placed some cannabis buds in a contact lens case, his wife said. Jane said she had no idea he'd done it. But why take such a risk?

"It's pretty simple," his son Ethan said of his father's plan to bring medical marijuana into Russia. "He thought he could get away with it."

Still, this lucky man, this man who always seemed to have things go his way, assumed this would be a situation that wouldn't end up so badly. Maybe he'd just get deported. Maybe he'd pay a fine or get a light punishment of some sort. Maybe.

Instead, the Russians charged him with drug possession and intent to sell marijuana to his students.

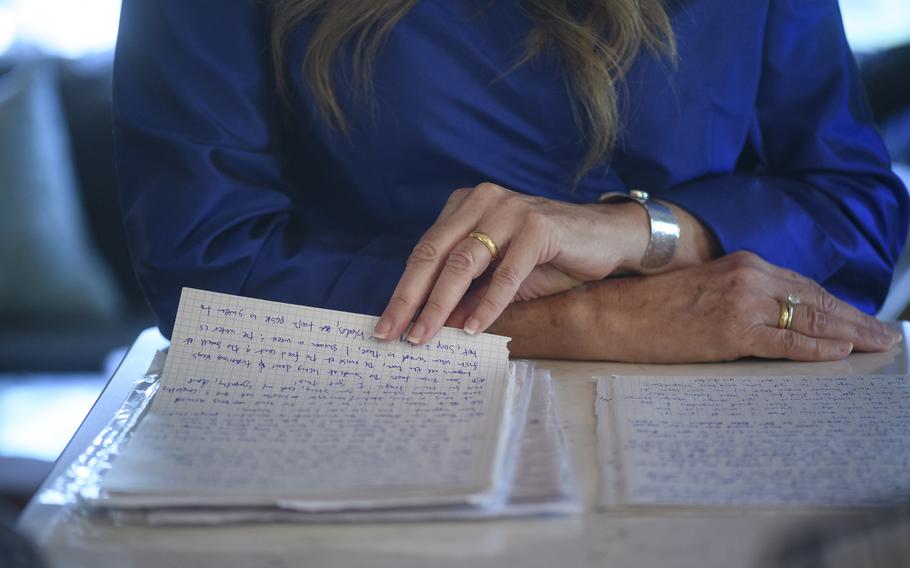

At home in Oakmont, Pa., Jane Fogel now wears her wedding ring with husband Marc’s wedding ring, as she reads the letters she has received from him since his imprisonment in Russia. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)

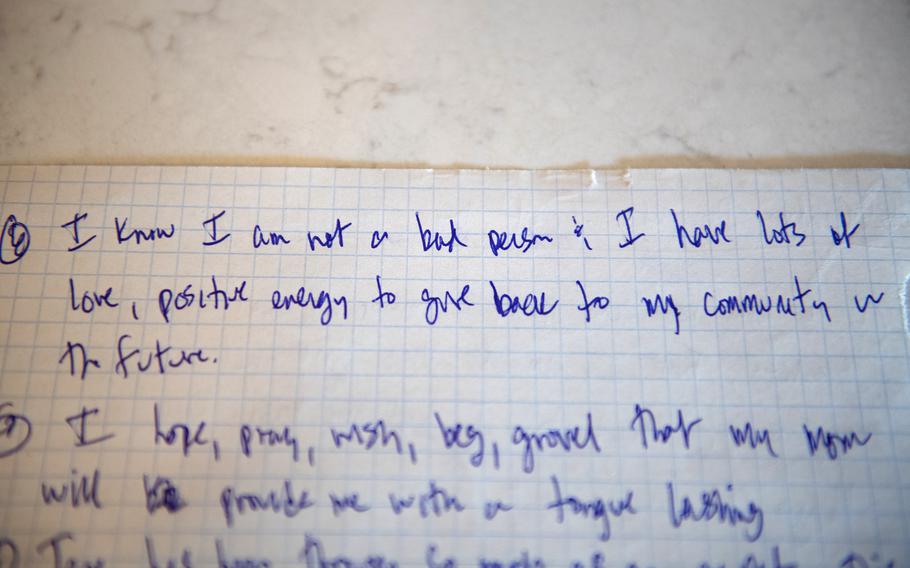

While waiting for his trial, Fogel kept a diary, pouring out his vacillating emotions, from optimism to despair and back again. On the first pages of a notebook with a blue cover, he scrawled 53 things that gave him hope or made him happy or that he looked forward to when — if — he won his freedom.

No. 1: "Jane is receiving 1,000s of supportive letters."

No. 8: "Another person got out after paying a fine."

No. 53: "I found a Frank Zappa picture in a Russian magazine."

He writes about the confusion and upheaval of being transferred over and over among the network of notorious pretrial detention centers. In one, he encounters a "guardian angel" whose brother sends them boxes of food; he invents a cornhole-style game using "gruel bowls" and dried apricots. In another, he has to kneel to get nasty food passed through a small window in his cell, and he's not allowed outside for days.

At one point he refers to his notebook as his "dark journal." He suspects the Russians are trying to "break" him, employing a method of creating misery, "tried & true & right now I feel it in my bones, my soul, it teems throughout my body." He senses a "lack of empathy from these heartless bastards."

He chastises himself for ruining his life and that of his family. He dreams of scary bears. He wonders whether he'll ever see his 93-year-old mother again. When he looks at his face in a mirror he thinks his "crying has carved new lines."

— — —

Marc Fogel did not deny trying to bring medical marijuana into Russia. What he asked for was leniency.

He promised the judge in his case that if he were released, he'd act almost like a tourism promoter, extolling the delights of Moscow and the affection he had for its residents — the same things he'd been telling his family and friends in the United States for years, according to Irina Pigman, a Russian-born business executive whose husband is from the United States.

Fogel thought he had a chance.

He probably didn't.

U.S.-Russia relations were strained then, as they are now, by U.S. support for Ukraine after the Russian invasion in February 2022.

Russian prosecutors had painted him as a "large-scale" drug dealer intent on selling drugs to his students and falsely labeled him an employee of the U.S. Embassy, assertions that were repeated in some Western media accounts.

At The Post's request, Jane Fogel provided documentation — payroll statements from two different years and an employee verification letter dated the month before his arrest — that shows her husband was employed by the Anglo-American School of Moscow. Additionally, McFaul, the former U.S. ambassador to Russia who befriended the Fogels in Moscow, said in an interview that Fogel was not an embassy employee or an American diplomat.

Jane Fogel also provided The Post with copies of her visas, which she said are the same type as those her husband received. At the time of his arrest, the school where they taught had sponsored their visa applications and they received a type of visa typically granted to professionals designated as "highly qualified specialists."

In previous years, they'd received visas sponsored by the U.S. Embassy that labeled them "technical employees," a term of art that allowed them to work in Russia at the invitation of the embassy and afforded them certain diplomatic protections, even though they were not employed by the U.S. government. The embassy was involved because the school had been chartered by the American, British and Canadian embassies but overseen by a separate school board. The change in the Fogels' visa status took place in 2021 when the school transitioned to being a nonprofit institution.

On the June day that Fogel was sentenced, Pigman watched the former teacher's face change as the Russian judge read a lengthy statement culminating in a 14-year sentence.

Jane Fogel looks through photos of her life traveling the world with her husband, Marc. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)

"It was like he grew old all of a sudden," Pigman said in a telephone interview from her home in Moscow. "He was stunned."

Three weeks later, Griner — the WNBA star who was detained in Russia on drug charges in February — pleaded guilty. She's awaiting sentencing. The family of Whelan, the ex-Marine serving a long sentence on spying charges, has been critical of the attention given to Griner's case by Biden. His sister said on CNN that she wished her brother was receiving similar treatment. Several days later Biden called her.

Jane Fogel remained quiet. She was following the guidance of U.S. officials and informal advisers who said public comments could make things worse for her husband. The tactic didn't seem to be working, and she's become increasingly impatient.

She has grown frustrated that she has not received more information from the State Department on her trips to Washington to discuss her husband's case. The officials are polite and empathetic, but they tell her almost nothing, she said. One of the most nettlesome and baffling dilemmas she's faced is that the State Department has not declared her husband "wrongfully detained," a designation granted to Whelan and Griner that would shift the handling of his case to the Office of the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, which negotiates releases.

Richard Burt, a former U.S. ambassador to Germany who is now a powerhouse Washington lobbyist, is one of those pressing for the designation. Burt has told her that she's only made it to the sixth floor at the State Department, but that they need to get her to the seventh floor where Blinken, the secretary of state, and the other highest ranking U.S. diplomats have offices.

Burt and McFaul have quietly been nudging the U.S. government on behalf of the Fogels. McFaul says his conversations through private channels with U.S. officials have led him to believe Marc Fogel is "definitely on their radar. It's not just the other two Americans."

Fogel is planning to appeal his conviction, but it's highly unlikely that imprisoned Americans can win release by going through the Russian court system. (The Fogels draw some hope from the possible precedent of a case involving Audrey Lorber, an American teenager whose was released from prison in 2019, one month after being caught bringing marijuana into Russia.)

McFaul has come to the conclusion that the "only viable option" for Griner, Whelan and Fogel is a prisoner exchange. In April, retired U.S. Marine Trevor Reed, who had been sentenced to nine years in prison, was exchanged for a Russian pilot who had been in a U.S. jail since 2010.

At home, Jane Fogel listens to talk of a prisoner swap and fights the urge to get her hopes too high.

One recent evening, McFaul sent her a clip of him discussing prisoner swaps during a cable news segment. Fogel pulled it up on her phone at the dinner table.

Unprompted, McFaul mentioned his "friend" who'd taught in Russia and was now serving 14 years in a Russian prison. There was a pause. She leaned forward and heard the anchor say what she'd been longing to hear.

Her mouth curled into a wide smile and she let out a little yip of delight: "They said his name!"

One of the letters Jane Fogel has received from her husband Marc since his 2021 detention in Russia. He was sentenced to prison earlier this year. (Jeff Swensen/The Washington Post)