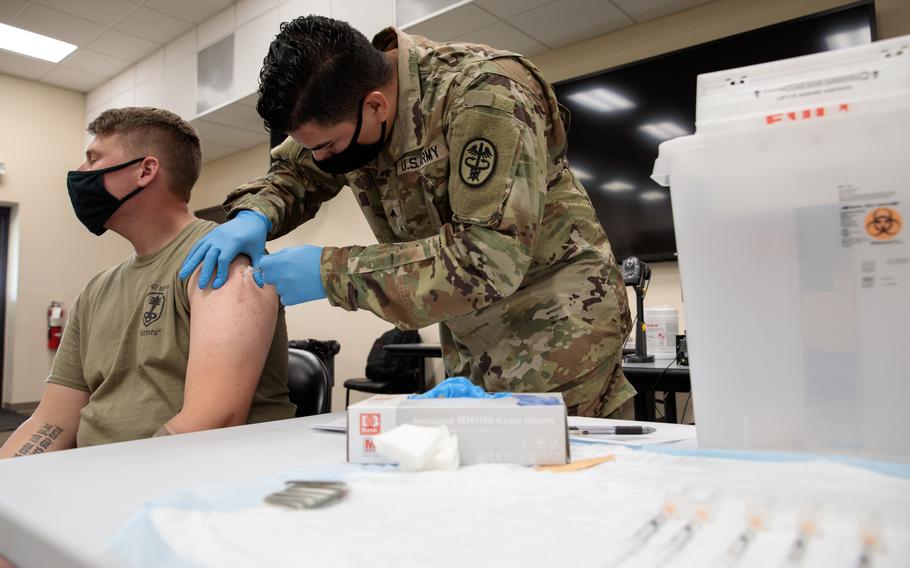

Army Cpl. Jonathan Leon Camacho, a practical nursing specialist with Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center at Fort Gordon, Ga., injects an Army Reserve soldier from the 447th Military Police Company with the coronavirus vaccination, Aug. 21, 2021, at Camp Shelby Joint Forces Training Center, Miss. (Brian Barbour/Arizona Army National Guard )

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

WASHINGTON — As an Arizona county braced for monsoon rains last week, nearly 100 members of the state’s National Guard filled sandbags and helped with other flood recovery efforts.

That same week, Oklahoma’s governor deployed the state’s National Guard troops to support firefighters battling a raging wildfire.

Guard members are routinely called up for natural disasters and other emergencies. They have helped combat the coronavirus pandemic, patrolled the U.S. border with Mexico, contained protests over racial injustice in 2020, deployed to wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and responded to countless fires, floods and hurricanes.

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill worry these vital services could be curtailed if the tens of thousands of National Guard members and reservists who have not complied with the Defense Department’s coronavirus vaccine mandate are discharged from the military.

“For decades, the National Guard has served as the backbone of saving Americans across the country in times of crisis,” Rep. Mike Waltz, R-Fla., wrote in an opinion piece for Fox News on Monday. “But when the next crisis comes to our shores, the U.S. will lack the number [of] Guardsmen and women to come to our rescue.”

Some 40,000 National Guard and 22,000 Reserve troops missed the vaccination deadline on June 30 and were subsequently cut off from some of their benefits and barred from participating in federal training, drills and other military duties.

Nearly a month later, the numbers have ticked down slightly. About 10% of the 336,000 Army National Guard troops, or approximately 33,600 members, had not received at least one vaccine shot as of Monday. In the total National Guard force of 440,000 soldiers and airmen, about 39,600 remain unvaccinated, according to the National Guard Bureau.

The number of Army and Air Force reservists who are not fully vaccinated continues to hover at about 20,000, most of them soldiers. Army Reserve and Army National Guard members were given seven months longer to receive the vaccine than any other service member in the military.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin last year ordered all active-duty, Guard and Reserve service members to get vaccinated and has said unvaccinated troops could face expulsion.

The potential loss of those troops, particularly amid the worst military recruiting environment since the Vietnam War, has raised alarms on Capitol Hill. The Army is expected to reach only 40% of its recruitment target this fiscal year and miss its recruiting goals by 40,000 personnel in the next two years.

Only 23% of young people between the ages of 17 to 24 are eligible to serve in the military without a waiver, according to Pentagon officials. Even fewer have the desire to enlist.

“The question is: Can the Army afford to discharge these soldiers in light of all those recruiting difficulties?” Rep. Mike Johnson, R-La., asked last week at a House Armed Services Committee hearing.

More than 50 House Republicans sent a letter to Austin on Tuesday requesting he reconsider the Defense Department’s vaccine mandate and issue guidance that considers natural immunity.

“At a time when the department is struggling to recruit qualified young men and women fit for duty to fill the ranks, and while China is embarking on a massive military buildup which threatens American interests around the world, we should not be hindering our own readiness and capabilities by punishing and forcing out experienced and dedicated Guardsmen and reservists,” the lawmakers wrote.

At a congressional hearing last week, Waltz, a colonel in the Army National Guard who is vaccinated, pressed Gen. Joseph Martin, the Army’s vice chief of staff, for a contingency plan.

“We’re talking about states potentially losing up to 20% to 30% of their guardsmen and women, replacing them in a very difficult recruiting environment, much less getting them trained to the capability they once were,” Waltz said. “I don’t know how you get there.”

Martin cautioned a decision on possible separations is still pending and expressed confidence that the new Novavax COVID-19 vaccine could boost compliance. The two-dose vaccine is based on conventional technology used in vaccines for the flu, whooping cough and hepatitis B and will be available in the coming weeks.

“[There’s] a lot of things to take into consideration as we move toward that decision, but each and every day, we’re making progress in terms of more soldiers choosing to vaccinate or their exemptions are approved,” Martin said. “We will have to manage our force but we’re talking about the future and we haven’t made that decision yet.”

A National Guard Bureau spokesperson said Tuesday that soldiers and airmen are still providing documentation of their vaccination and said the numbers released publicly might be lagging behind those recorded internally.

Nearly 11,000 members of the Army National Guard and about 5,000 reservists have refused vaccination as of July 21, according to Army data. Six Guard members and two reservists were given exemptions for medical reasons and none have been exempted for religious reasons. More than 3,000 are requesting religious exemptions and nearly 80 have been denied.

The Army has discharged about 1,400 active-duty soldiers for refusing to be vaccinated.

Potentially adding thousands from the National Guard and the Reserve to that figure could have a sizable impact, according to experts.

“The order of magnitude is very large,” said Katherine Kuzminski, director of the Military, Veterans, and Society program at the Center for a New American Security, a left-leaning Washington think tank. “When you’re talking tens of thousands — that’s ten battalions’ worth for 10,000 people and that’s significant.”

The loss of troops would be felt mostly domestically now that the war in Afghanistan is over, she said. During the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military heavily relied on the National Guard and reservists for combat support and logistics. But today, those soldiers and airmen are primarily deployed for local emergencies, she said.

“Given that we’re in the middle of both wildfire and hurricane season, that could have potentially detrimental effects on the availability of manpower for dealing with domestic crises where we rely on the Guard,” Kuzminski said. “It raises more challenges for the ability of the United States to meet crisis moments here at home.”

There can be workarounds, however. In certain states, Guard members banned from federal duties might still be able to participate in state-level operations through the authority of a governor, Kuzminski said.

Several Republican governors have fought the federal vaccine mandate for their National Guards, with at least seven seeking to allow their troops to refuse the vaccine. Alaska, Oklahoma and Texas filed lawsuits over the vaccination requirement.

Austin has refused to budge, writing to governors that “Covid-19 takes our service members out of the fight, temporarily or permanently, and jeopardizes our ability to meet mission requirements.”

Federal officials maintain that governors have no legal say over the fate of Guard members who do not get vaccinated while state officials argue the National Guard is under the jurisdiction of governors and is not subject to federal mandates unless federally deployed.

Trupti Brahmbhatt, a senior policy researcher at the Rand Corp. think tank and a Navy veteran, said those dueling viewpoints have influenced local National Guard vaccination rates, with members following the lead of their governors. In states such as Oklahoma, where the governor is an outspoken critic of the mandate, Guard members may believe they will be protected from separation, she said.

It is unlikely that the military will dismiss all the Guard and Reserve members who do not abide by the mandate, Brahmbhatt said.

“It’s not actually going to happen to the big, huge extent that we expect,” she said. “There might be some, but you also have to think about the recruitment and retention issue that active duty is having right now.”

Kuzminski said the Defense Department must weigh those personnel shortfalls with what defiance of the vaccine mandate signifies: the failure to comply with an order.

“The whole foundation of military action and conflict is based on the ability to follow through with a lawful order and so that is the conundrum that the services are in,” she said. “They don’t necessarily want to retain people who have indicated that they won’t follow a lawful order when it comes to a vaccination.”

Waltz and other lawmakers have questioned the validity of that order, arguing service members should be able to decide the personal health risks that they are willing to incur from infection now that it is known vaccines do not stop the spread of the coronavirus.

“I fully understand — as a 26-year veteran myself — good order and discipline and an order is an order,” Waltz told Gen. Martin last week. “You order the platoon to charge the machine gun on the top of the hill, they’ve got to follow it. But I also think it’s incumbent on us as leaders to constantly evaluate the cost and the risk of our orders. Maybe charging that hill is going to be too costly to that unit.”