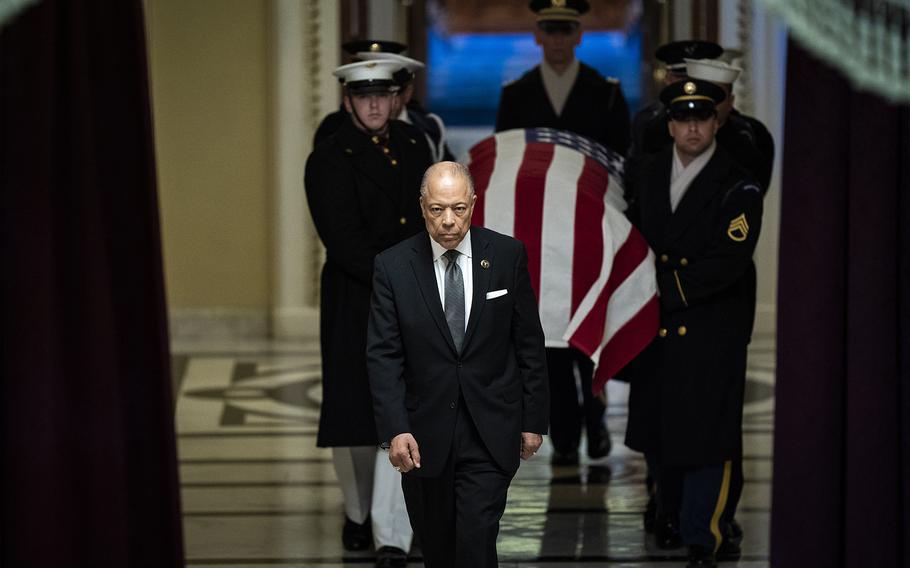

House Sergeant at Arms William Walker leads a casket carrying Rep. Don Young (R-Alaska) in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol on March 29, 2022, in Washington, D.C. (Jabin Botsford, Pool/Getty Images/TNS)

WASHINGTON (Tribune News Service) — Suspects did not want to be caught in the crosshairs of William J. Walker.

“If you were a target of mine, I had your picture in the [car] visor,” said the former agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration. “I knew as much about you as I could, and I just focused on you.”

Walker, who now heads up security on the House side of the Capitol, said his thoughts on his ride home often wander to whether he accomplished what he set out to do.

“I jot down notes and then I make an assessment at the end of the night,” he said, explaining he gives himself a grade. “Some days I’m an A — some days I’m disappointed.”

He has a lot to think about. It’s been more than a year since Walker accepted the job of House sergeant-at-arms, and he landed in the middle of chaos. He took over from acting leader Timothy Blodgett, after Paul D. Irving resigned in the fallout from Jan. 6, 2021.

That day, Walker was still commander of D.C.’s National Guard, helplessly watching pro-Trump rioters overwhelm Capitol Police officers as his guardsmen sat loaded on buses waiting to deploy.

In the aftermath of the insurrection, he testified that though police pleaded for the guard’s help, he didn’t get a go-ahead from the Pentagon to send troops to the Capitol until hours after the complex was invaded. He described “unusual” restrictions put on his ability to deploy and said Defense officials had concerns about “optics.”

Those orders contrasted with the previous summer, when protesters took to the streets after the murder of George Floyd. Walker defended troop presence in Washington and said he believed it helped protesters remain peaceful.

“I think deterrence matters,” he said. “Some people have to touch the stove. But most of them, if there’s a sign up that says high voltage, most people won’t touch it.”

When a Defense Department inspector general report later contradicted Walker’s testimony, saying he’d been called earlier in the afternoon, he publicly criticized the report, calling it “inaccurate” and “sloppy work” in an interview with The Washington Post.

Sticking to his story is nothing new for Walker, even when it’s unpopular. He’s appeared in court against criminals he investigated at DEA, and he testified as part of a lawsuit that alleged the department discriminated against its Black agents.

His years of experience are being put to the test as Capitol security remains in the spotlight, thanks in part to the House select committee investigating the attack. As images of that terrifying day play once again on television, questions still swirl about how to protect Congress in the future — and how much of those plans to share with the public.

Walker said he’s up for the challenge. “I’m not afraid of anybody or anything — but heights,” he said.

‘No destination’

As the top law enforcement official on the House side of the Capitol, Walker inherited a mixed legacy.

“Security is a journey. There’s no destination,” he said. “We are safer in this complex than we were before. Members are safer than they were before.”

After 9/11, for example, Congress fortified itself against bombs and terrorist attacks by putting up bollards and building the Capitol Visitor Center, and in other invisible ways. But those safeguards didn’t stop the pro-Trump mob 20 years later.

Since being named to the post last March, Walker said his office has expanded to about 170 employees. That number does not include the team led by his counterpart on the Senate side or the Capitol Police force, which had 1,849 officers as of this spring.

He’s hired people who worked for agencies like the Secret Service and State Department in an effort to adapt to the new threats, especially when members of Congress are traveling and in their districts. And technology is a key part of the equation, he said.

“The people’s house will always be the people’s house,” he said. “But there has to be a robust security apparatus that can quickly at a moment’s notice protect the complex.”

House Democrats proposed giving more than half a billion extra dollars in fiscal 2023 to the Architect of the Capitol to beef up the complex in the wake of Jan. 6. His office would get an $11 million boost, and be tasked with things like researching gunshot detection systems, improving the use of ballistic shielding, and working to expand alert systems.

For the already rattled workers at the Capitol, December brought another scare when a House employee passed through security screening with a handgun. Walker acknowledged the seriousness of that incident but declined to share the plan to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

“We’re still developing what we were going to do as far as making sure a weapon does not come through anymore,” he said. “So we probably need better equipment out there and more vigilance in doing the job.”

Fencing has been another pain point on Capitol Hill, with tall barriers encircling the complex for months after the Jan. 6 attack. A fence went back up before a protest in September and ahead of this year’s State of the Union address, and now one rings the Supreme Court after justices overturned the landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade.

Walker wouldn’t say what would trigger the decision to erect another fence, other than it wouldn’t be taken lightly. But he said he’s confident in the new faces on the Capitol Police Board, made up of the House and Senate sergeants-at-arms and the architect of the Capitol, plus the nonvoting Capitol police chief.

The board came in for heavy criticism after Jan. 6 for failing to prepare, and almost everyone headed for the exits, except Architect of the Capitol J. Brett Blanton.

While some lawmakers and outside groups have called for more public transparency, Walker said minutes from police board meetings and other operational decisions need to stay private.

“Talking about what we’re doing does not make the Capitol safer,” he said.

‘Danger, excitement, adventure’

Walker is the 38th House sergeant-at-arms and the first Black person to hold the post. Being the first person of color during his career has made him feel responsible for being “as close to perfect as possible.”

“I was the only African American in my agent class with DEA,” he said. But he hopes his influence can help create a more diverse group of future leaders who may have been passed over.

People in his life pushed him to get a degree from the National Intelligence University and take a liaison role with the White House’s drug policy office, and now he wants to pay it forward.

“There are no self-made men or women. Maybe there are, but I don’t know any,” he said. “It’s been my experience that you need three people in your life if you’re going to be successful in a career. You need a coach, a mentor and a sponsor.”

Walker grew up in Chicago’s Auburn Gresham neighborhood and attended Catholic schools, which he said taught him the value of public service.

As a child, he was particularly captivated by two television shows: “The Untouchables,” about a group of incorruptible agents fighting crime in 1930s Chicago, and “Combat!” a drama about Americans fighting in France during World War II.

“Earlier in my life, I remember clearly we had riots in Chicago, civil unrest,” he said, describing how he saw national guardsmen stand side-by-side with law enforcement.

As a high schooler, Walker said he went to a federal building to get information on how to join the DEA. He said he was told he had to be a certain age and have a college degree. So he went to the University of Illinois and waited for his birthday.

“I decided, well, joining the National Guard will allow me to be an American soldier part time and then be a DEA agent full time,” he said. “It was a symbiotic relationship.”

In his military career, Walker was deployed to Afghanistan and served at the Pentagon after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. At DEA he worked stints in Chicago, New York and Miami, as well as in international posts and at the White House.

His years there were filled with what the DEA represented for him: “Danger,” “Excitement,” “Adventure.”

Welcome back

Walker said he didn’t expect to be approached about taking over as sergeant-at-arms — his plan was to wrap up a doctorate degree at Benedictine University and finish with a full 40 years in the Army.

“There was no way I could say no,” he said.

The stoic veteran, who has traveled to about 70 countries and met multiple presidents, said he was prepared for the job, but sometimes things still awe him.

One of those times was on April 28, 2021, during a joint session of Congress.

“Madame Speaker, the president of the United States,” he said, slowly walking toward the rostrum where a female vice president and speaker waited for the first time in history.

Before his voice echoed through the chamber, the moment hit him — his meeting with Joe Biden wasn’t the same as past meetings with presidents.

This time Walker was inviting Biden, a former member of the Senate, back to the building he was now in charge of securing.

“It was an amazing feeling to stand next to the president, to welcome him into the Capitol,” he said. “I said, ‘Mr. President, welcome back to the Capitol.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I’m home.’”

©2022 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

Visit cqrollcall.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.