Burglars were arrested early on the morning of June 17, 1972, after breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate building. The ensuing scandal riveted the nation and forced the resignation of a president. (National Archives)

On Friday, America will mark the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in. The scandal that riveted the nation and forced the resignation of a president is taught in schools as a dark chapter in history. It is more than that, however. Its legacies have shaped the conduct of politics and public attitudes toward government ever since.

Watergate, along with the Vietnam War, marked a dividing line between old and new, ushering in a changed landscape for politics and public life — from a period in which Americans trusted their government to a period in which that trust was broken and never truly restored.

“It’s a hugely important historic moment,” said Julian Zelizer, a historian and professor at Princeton University. “And we entered a new era when it was over.”

Though not a straight line by any means, the links between former president Richard Nixon and former president Donald Trump also are clearly identifiable, from their ruthlessness to the win-at-any-cost calculus of their politics. That their presidencies played out differently — Nixon resigned amid impeachment proceedings; Trump served his entire term and may seek another despite twice being impeached but not convicted — is testament to a more deeply polarized electorate, the erosion in the strength of democratic institutions and the transformation and radicalization of the Republican Party.

The aftermath of the Watergate scandal opened up the operations of Congress but also contributed to making the legislative body less manageable. The scandal helped change the way reporters and government officials interacted with one another. A more adversarial relationship has existed ever since. The era spawned reforms that worked and some that did not, from campaign finance to intelligence.

Politically, both major parties were affected. A seemingly broken Republican Party reconstituted itself with a more anti-government ideology. Democrats, led by the big class of 1974, slowly began a transformation away from the lunch-pail coalition of white working-class voters and toward a more diverse coalition that now includes highly educated coastal elites.

Not everything that has happened since Watergate is directly attributable to the scandal itself. Some changes in society and politics were already beginning to be felt before burglars were arrested early on the morning of June 17, 1972, after breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate building. But subsequent investigations; the indictments and convictions of Nixon administration officials; the impeachment articles passed in the House Judiciary Committee; and Nixon’s resignation combined into an event that shattered the confidence and idealism of previous decades.

Garrett M. Graff, author of the book “Watergate: A New History,” describes Watergate as a dividing line in history — the event that moved Washington from a sleepy capital dominated by segregationists, veterans of World War I and print newspaper deadlines to a capital ruled by a new breed of politicians, a more adversarial media now in the digital age and a country deeply skeptical of government and politicians.

“The Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers and Watergate ... fundamentally rewrote the relationship between the American people and their government,” Graff said, “and caused a collapse in the public’s faith in those institutions that our nation’s leaders are still struggling with today.”

As William Galston of the Brookings Institution put it, “We have been living for nearly half a century in the world that Watergate made.”

John Dean at the Senate Watergate Hearings in 1973. (Brian F. Alpert, Keystone Press Agency, Zuma Press/TNS)

The shattering of trust in government

The Pew Research Center has a graphic on its website that charts the decline of trust between citizens and government. It is a vivid illustration of the world that Watergate helped to make.

The graphic begins in 1958, near the end of the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower, when 73% of Americans — majorities of both Democrats and Republicans — said they trusted the government to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time.” In the fall of 1964, despite the assassination of President John Kennedy a year earlier, which some people see as the moment when the idealism of the period was broken, trust peaks at 77%.

By 1968 and the end of the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, with Americans violently divided over Vietnam and shaken by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the line on the chart heads downward but still with a majority expressing trust. From there, it begins to fall further. By late 1974, after Nixon left office, just 36% of Americans say they trust their government.

“The trust has never really rebounded to the pre-Watergate levels,” said Joycelyn Kiley, Pew’s associate director of research.

The decline in trust affected virtually every institution over time. “One way of thinking about it is that Americans ceased to trust the men in suits — whether those men in suits were lawyers, university professors, the press and especially, especially, the government,” said Bruce Schulman, a professor of history at Boston University.

Kiley said more than just the Watergate scandal has caused all this. But her point about the lack of a rebound was underscored by Pew’s latest measurement, released last week, which found that today, just 20% of Americans say they trust their government to do the right thing all or most of the time. At the same time, Americans see a continued role for government and say that government is not doing enough for several groups of people.

One irony of the decline at the time of Watergate is that democracy had worked, from the actions of government institutions to the public’s response.

“It’s really important to understand that the process that took down Nixon was driven by an extraordinary level of civic engagement,” said Rick Perlstein, a historian who has written multiple volumes about the history of the 1960s and 1970s. “The response was not this kind of nihilistic response we would see now.”

But while the institutions worked, the revelations about the vastness of the Watergate conspiracy painted an ugly portrait of the use and abuse of power during Nixon’s presidency. “The courts, the Senate, the Congress, the House Judiciary Committee, the press. Everything worked the way it’s supposed to. But people ended up with a very bad taste in their mouth,” said Jim Blanchard, who was elected to the House in 1974 as a Democrat from Michigan and later served as governor.

Coupled with the governmental lying about Vietnam, exposed most vividly with the publication of the Pentagon Papers first by the New York Times and later by The Washington Post, government was under attack from the left and the right, though for different reasons.

“It’s amazing how fast we shifted from the post-World War II trust mode, which lasted for about 20 years, into the post-Vietnam, post-Watergate mistrust mode,” Galston said. “Once we lost that trust, we never regained it.”

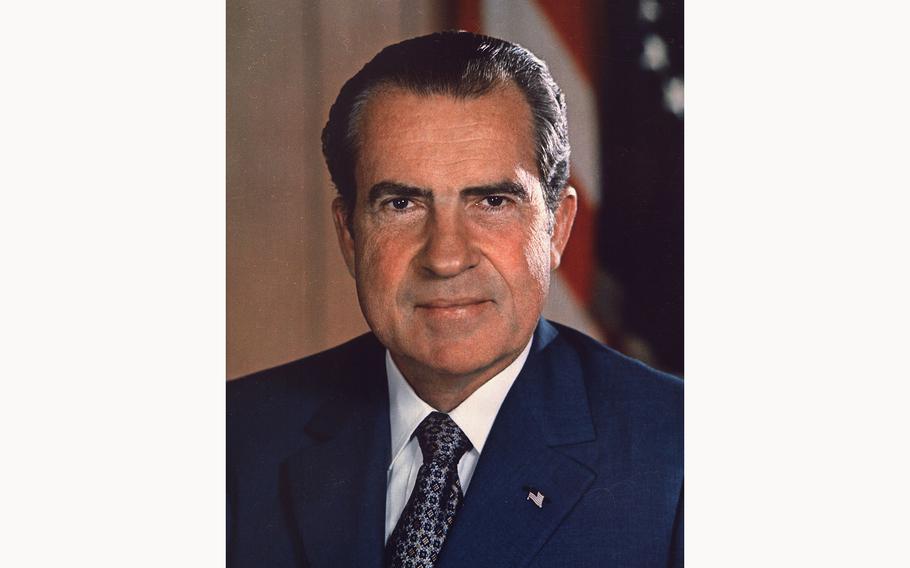

Richard Nixon’s presidential portrait. (WikiMedia Commons/Department of Defense)

The “Watergate babies” come to Washington

Three months after Nixon resigned and two months after he was pardoned by President Gerald Ford, the 1974 midterm elections dealt a seemingly devastating blow to the Republican Party. The election produced a huge new class of lawmakers, more than 90 in all, including 76 Democrats in the House who became known as the Watergate babies.

These Democrats were diverse in their ideologies — some moderates and conservatives but many liberals. They shared a passion for reform. “The collective sense was that it was time to change the seniority system,” said Tom Downey, who was elected to the House as a Democrat from New York at age 25. “We wanted this to be a more accountable institution.”

Leon Panetta, who had come to Capitol Hill in 1966 as a staffer and was elected as a Democrat to the House in 1976 representing California, said, “You really had a sense that you had been empowered by the American people to straighten out Washington and to implement reforms and to really do things different in a way that would hopefully restore trust.”

“There were so many new members that the old guys couldn’t come and encircle them and try to convince them that they should be quiet for the first 10 years and stay out the way,” said former congresswoman Pat Schroeder, a Democrat from Colorado who was elected in 1972.

The new class helped oust three powerful committee chairmen, something unheard of at the time. Other reforms redistributed power in the House.

“We had opportunities that no new members had historically — to speak, to negotiate, to assert our power,” said Phil Sharp, elected to the House as a Democrat from Indiana in 1974. He added, “It really meant we had more influence in the subcommittee, we had more influence on the House floor, we had more influence in the conference committees.”

The result was a more open and transparent House but also a more cumbersome legislative body. Today, every member of Congress is an independent actor with access to the media and many to big money and, if motivated to do so, the ability to frustrate leadership. That is an offshoot of what started in the 1970s.

“I believe that over time, it reduced the ability to get to a decision, which I would argue is one of the compelling issues in government today,” Sharp said. “Ultimately, democracy must prove not that it’s open, it has to prove that ... it can actually make a decision on something of significance.”

“For a legislator and particularly for a leader, your goal is to pass legislation,” said John A. Lawrence, author of the book, “The Class of ‘74: Congress After Watergate and the Roots of Partisanship” and a former chief of staff to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif. “And it becomes harder when you honor transparency over effectiveness.”

Then-House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill Jr., D-Mass., among others, had worried about too much openness, especially the decision that would allow C-SPAN to begin to televise House floor proceedings in 1979. “They understood that the more public the system was, the less power the old order would have,” said former speaker Newt Gingrich, R-Ga.

Elected in 1978, Gingrich said he found the institution “astonishingly open” to newcomers on a mission, like himself. He used the levers available in a more open institution — from television in the House to new ethics rules — to chart a rise to power that in 1994 would drive Democrats from control in the House for the first time in 40 years.

The U.S. Capitol as seen on May 8, 2019. Watergate set off fresh discussion about the balance of power between Congress and the executive branch amid concerns about an imperial presidency. This led to new laws designed to whittle away at the powers of the president. (Carlos Bongioanni/Stars and Stripes)

The explosion of reform

The post-Watergate years of the 1970s saw a flurry of new laws designed to address issues raised by the scandal.

In 1974, Congress amended campaign finance laws after revelations about the abuses of money by Nixon’s reelection committee — thousands of dollars stuffed in safes and used for hush money, and illegal contributions solicited from major corporations. The new law put caps on how much people could contribute to candidates and how much federal candidates could spend, created partial public financing through matching funds in presidential campaigns and established the Federal Election Commission.

Over time, the reforms were weakened both by Supreme Court rulings and by workarounds campaign lawyers devised. A major change came in 2010, when the high court gave corporations and other outside groups the authority to spend unlimited amounts of money to influence campaigns. The Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision resulted in a proliferation of so-called super PACs and independent committees and the use of “dark money” (funds in which donors are not disclosed), leading advocates to say that a decades-long effort to reform campaign finance had failed.

Watergate set off fresh discussion about the balance of power between Congress and the executive branch amid concerns about an imperial presidency. This led to new laws designed to whittle away at the powers of the president.

In 1974, Congress approved the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act, which established a new process for federal budgeting by lawmakers, created the Congressional Budget Office and sought to limit the power of the president to override decisions made by lawmakers on how to spend the government’s money. The 1973 War Powers Resolution, a response to Vietnam, was designed to prevent future presidents from engaging in military conflicts without having consulted Congress in advance.

But these, too, have proved ineffective. Presidents have routinely ignored these requirements, and a compliant Congress has offered minimal resistance. “Too often, Congress was willing to basically allow presidents to do what they have to do in order to deal with the challenges that are out there,” Panetta said.

The 1978 Ethics in Government Act set new financial disclosure requirements for public officials and put restrictions on lobbying by former officials. The act’s Title VI created the system for the appointment of special prosecutors by the attorney general to investigate allegations against executive branch officials.

More broadly, the combination of the ethics legislation, calls for more rigorous congressional oversight and the work of independent counsels has carried forward to the present day. “Watergate had inaugurated an era of politics by other means, where political opponents attempted, instead of defeating one another’s arguments, or winning elections, to oust each other from office by way of ethics investigations,” historian Jill Lepore wrote in “These Truths.”

Between 1970 and 1994, according to Lepore, federal indictments of public officials went from “virtually zero to more than thirteen hundred.” The effect of all this “also eroded the public’s faith in the institutions to which those politicians belonged.”

Of all the efforts to clean up after Vietnam and Watergate, reforms of U.S. intelligence agencies have been generally the most successful and long-lasting. The reforms grew in part out of hearings by a select Senate committee headed by then-Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, which investigated questionable and illegal covert actions aimed at foreign leaders and U.S. citizens by the CIA, the FBI and the National Security Agency.

Then-Sen. Gary Hart, D-Colo., was a member of the committee and remembers vividly the day when CIA Director William Colby came to testify and delivered to the committee what were known as the “family jewels,” a compendium of egregious actions by the agency, including attempts to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Out of the committee’s findings, Congress established congressional oversight committees with prescribed rules for consultation for any covert activities and requirements for presidents to sign official findings to authorize covert activities. “We saved the CIA,” Hart recalled. “If nothing had been done to rehabilitate the agency, it would have very seriously undercut their credibility.”

John McLaughlin, a former CIA deputy director and for a brief time acting director, was a recruit in training during this period in the 1970s and described these changes as appropriately intrusive.

“I’m a big supporter of oversight,” he said, “because without it, you cannot count on the trust of the American people for an institution that has great power and is asked to do difficult things by the president. Even at that, it doesn’t assure that trust or that confidence, but it’s the closest thing we have.”

Kathryn Olmsted, a professor of history at the University of California at Davis and author of the 1996 book “Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI,” said that the reforms “fell short of what Senator Church wanted.”

“Church thought exposing all these abuses would restore Americans’ faith in government,” she added. Instead, the committee’s revelations gave rise to more anti-government conspiracy theories.

The impact on the political parties

Watergate left the Republican Party decimated, or so it seemed.

“The conventional wisdom was, oh, the Republicans are done for a generation,” said Beverly Gage, a professor of history at Yale University. “That’s not what happened. But it is more true if you said it’s the Nixon wing of the Republican Party [that is dead]. Watergate was much more devastating to that part of the Republican Party.”

A Republican Party personified by politicians like Ford, Nelson Rockefeller and George Romney was taken over by a new, Southern and Sun Belt-based conservative movement that viewed government with considerably more hostility. In 1964, this brand of conservatism, led by Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, went down in defeat to Johnson. By 1980, with the election of Ronald Reagan, the era of New Deal liberalism had been blunted by a conservatism that would hold sway in the party and the country for decades.

Schulman, who wrote “The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society and Politics,” said that, while it is an oversimplification to say that Reagan’s election was a response to Watergate, the reaction to the scandal nonetheless provided fertile ground for the conservative, anti-government ideology Reagan championed.

“You have to remember that for most of the post-World War II period, liberalism, for better and worse, had really been the reigning public philosophy in the United States,” Schulman said. “One of the ways that Watergate is very important is in the transformation of the Republican Party into a conservative party. ... And after 1980, it was, by all effects, really a conservative party.”

Zelizer noted, “When Reagan in 1980 is lashing out against government, I just think there’s more support at some level for the kind of arguments he’s making, because people have a Richard M. Nixon, even though he is a Republican, they have a Richard M. Nixon in their mind.”

Reagan was one of Nixon’s staunchest defenders. He described the hearings before the Senate Watergate committee chaired by Sen. Sam Ervin, D-N.C., in the summer of 1973 as a “lynching” and praised the president so consistently that, according to Perlstein, the columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak reported that some Reagan advisers worried that his support for Nixon had the potential to hurt him politically.

“They say [in the column] the people who want to make Ronald Reagan president are terrified that he won’t let go of his support for Richard M. Nixon and this is going to destroy his career,” Perlstein said. “And of course, the irony is, and this is kind of my argument, that it didn’t destroy his career. It was the foundation for his political rise.”

Meanwhile, the Democrats were to undergo their own transformation, thanks in part to the infusion of new members of Congress beginning with the 1974 election. “They tended to be more educated, more professional than previous tranches of Democrats, less connected to the working class, more interested in issues that weren’t within the four corners of meat and potatoes,” Galston said.

As Perlstein said, “It’s not the beer-and-a-shot, lunch-pail Democratic Party anymore.”

No one more typified the new breed than Hart, who was elected to the Senate after managing George McGovern’s 1972 president campaign that ended in a landslide loss to Nixon. “I was so angry at Watergate and the fact that it had not had the impact on the ‘72 campaign that it should have had and eventually did have,” Hart said in explaining why he ran in 1974.

Hart helped lead the party in new directions, and his eventual challenge to — and near-victory over — former vice president Walter Mondale in the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination contest pitted the old Democratic Party, tied to powerful labor unions, against a newer Democratic Party more oriented to rising forces of technology and to issues such as the environment and globalization.

The debate over what kind of party the Democrats should be, which was aired out that year, continues to echo today, as the Democrats wrestle with the demands of a more vigorous liberal wing and the desire to win back some of the White working-class voters who defected to the Republicans starting in the Reagan years.

The adversarial press

Watergate didn’t just change politics; it also changed journalism. Watergate made journalism glamorous. Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein became celebrities. Investigative journalism expanded into all corners of the news media.

In the same way that the public was losing trust in institutions, journalists were losing trust in government officials. After the lies about progress in Vietnam and the lies from the Nixon White House, reporters brought a more skeptical eye to the statements of government officials.

Gone were the cozy days when a reporter could play poker in the Oval Office with a president or when the private lives of politicians were considered off limits to reporting (as reporters did in turning a blind eye to John Kennedy’s philandering) unless it affected public responsibilities.

“A lot of journalism prior to that time was very deferential to political leaders,” Lawrence said. “You didn’t say certain things, and that wasn’t so good either. But I think a lot of younger people learned that the way you get ahead, just like members [of Congress] learned through oversight, that the way you get your name in the papers is by making a splash and by making accusations of wrongdoing or corruption. That culture ... became very, very powerful.”

Critics of the press believe that this has helped to color and coarsen political discourse ever since, that the DNA of journalism became strictly adversarial and that, despite the societal value of accountability reporting, it has had deleterious side effects on politics and governance.

“Everyone wanted to kind of have a pelt on the wall,” Perlstein said. “Every reporter wanted their own kind of scandal. And one of the consequences was a tendency to elevate peccadilloes to the status of scandals.”

The counter to this is that, by holding government officials accountable, vigorous and intrusive journalism leads to more effective and responsive government. Without the probing eye of journalists, corruption and malfeasance would be even greater than it otherwise would be. The decline of local newspapers, caused by the technological disruptions of the past few decades, has provided real-time examples of the absence of accountability journalism in cities and state capitals.

Leonard Downie Jr., who edited many of the Watergate stories at The Post in the 1970s and later succeeded Ben Bradlee as executive editor, acknowledged that as investigative reporting spread throughout the industry, “some corners were cut” by some investigative reporters. “Not everybody could bring down a president,” he said. “Not everybody could get somebody to resign or go to prison.”

That, he said, does not outweigh the fact that investigative journalism is now one of the most important roles of the American news media. “Holding power — all forms of power — accountable to American citizens is a good thing. And I just don’t worry about this adversarial aspect. I think that’s fine. I do not see a downside.”

The rise of polarization

Scholars and politicians debate when the extreme partisanship and polarization that defines today’s political climate really took root.

Though there was partisanship around the Watergate investigation, in the end, the conclusions were bipartisan, with a handful of Republicans joining Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee to vote for articles of impeachment and Republican elders going to the White House in the final days to tell Nixon it was time to go.

The 1976 presidential race between Ford and Jimmy Carter featured two relatively moderate politicians. In Congress, with the parties far less homogenized than today, Democrats and Republicans did work together on issues. By today’s standards, it was a far more genteel era.

Many analysts point to the Republican victories in 1994 and the elevation of Gingrich to the speakership as the moment when the current era of polarization and partisanship took hold. Others say the partisanship was building during the 1980s, with Gingrich and GOP backbenchers using different tactics to attack the entrenched Democrats, even as Reagan and O’Neill enjoyed a cordial relationship despite their ideological differences.

Lawrence, the historian of the class of 1974, believes the reforms those freshman members of Congress helped to force through the legislative branch were responsible. “Some of these reforms actually facilitated a rise in partisanship,” he said, “because they enabled people who otherwise might have been blocked from playing a more political or more public role in the more traditional management of the House — they gave them platforms to do so.”

Nixon also shares in the blame. Though on domestic issues he was, by today’s standards, relatively liberal, his campaign style in 1968 and 1972 was divisive and polarizing, using race, law and order, and cultural wedge issues to create cleavages in the electorate.

Gingrich believes the polarization was building even before Watergate and points to Reagan as evidence, describing Reagan, for all his geniality, as a polarizing politician. Speaking of Reagan’s emergence as a national figure in the 1960s, he said, “You had a polarization that was beginning to grow, and Reagan understood and knew how to deal with it pleasantly. But he was clearly a polarizer.”

Gage noted that even before Watergate, there were many people who were arguing that the country would be better off with more tightly organized political parties that would provide clearer ideological choices for the voters. “That’s where we’ve ended up half a century after Watergate,” she said. “And it’s turning out to be a real problem.”

Former President Donald Trump departs after speaking to supporters during a rally at the Iowa State Fairgrounds on Saturday, Oct. 09, 2021, in Des Moines, Iowa. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

The road from Watergate to Donald Trump

Those who have studied Watergate see a line that travels from that scandal to the Trump presidency. Part of this is because of the similarities between Nixon and Trump — the self-pitying nature of their personalities, the venality exhibited during their presidencies, the demonization of their opponents.

Nixon sought to undermine the Constitution to assure that he would win the 1972 election and then covered it up, for which he paid the price of forced resignation. Trump sought to undermine the Constitution to overturn an election he had lost in 2020. He didn’t cover up his efforts, though exactly what was going on still hasn’t been told in full. Instead, he attempted to build his case on a foundation of lies.

But the parallels are limited in part because the two presidents governed in two different eras. Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., was a law student and legislative staffer to a Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee during Watergate. Today she is a member of the Jan. 6 House panel that is investigating not just the attack on the Capitol but the broader effort to subvert the 2020 vote.

“We are in a political environment that is more sharply partisan than was the case during the Watergate era,” she said. “And you’ve also got people who lie with impunity and feel that there’s no downside to it. I mean, when Nixon was caught in lies, he resigned.”

There was a moment early in the work of the Ervin committee, cited in Graff’s history of the scandal, when White House lawyers were warning that any officials called to testify would decline to answer the panel’s questions. The response from one committee attorney was to say that anyone who did that in a public forum would be ruined. Trump’s White House routinely refused to cooperate with congressional investigations and did so without being held to account and with the support of Republican lawmakers.

Graff highlighted the consequences of the differences between the Watergate period and today. “You see, over the course of the two years that Watergate takes to play out, the delicate ballet and dance of how our system of checks and balances works,” he said. “Watergate requires every institution in Washington to play a specific role and to do it successfully.”

In the Trump years, that system of checks and balances broke down. “The media played their role,” Graff said. “The Justice Department, you know, arguably played their role. The FBI arguably played their role. But then when it came to Capitol Hill, the House and the Senate fell short. Looking back at Watergate, the members of Congress in the House and the Senate on the Republican side acted first as members of the coequal legislative branch. ... What we saw in the Trump years was the opposite, which is Republicans on the Hill acted first as Republicans and second as members of Congress.”

Trump’s presidency can be seen as the culmination of what began with Watergate. Today is a time of heightened distrust in government, weakened institutions, a more polarized electorate, greater partisanship, a fractured and more politicized media, and a Republican Party with a stronger anti-government ideology and more ruthless in its approach.

Trump seized on all of this, and more, to become president, to exercise his powers in office and to try to stay in office after he had lost to Joe Biden. “I think it’s pretty clear that he exposed as president some of the real weaknesses and dysfunction of all these institutions,” Zelizer said, “from Congress to the media to other elements of administrative and executive power. And I think it’s true that they’re just not working as well right now as they had when this whole story started.”