On his Twitter feed, President Joe Biden said that In 1994, he took on the NRA to pass a 10-year ban on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines and that he’ll do it again as president. (Twitter)

WASHINGTON - Then-senator Joe Biden's signature crime bill had ground its way through Congress after months of tedious effort. But after an unexpected flare-up over guns raised the threat of a filibuster, the lawmaker from Delaware took the Senate floor for an impassioned plea.

"We can vote to keep these deadly military-style assault weapons on the streets, where we know they have one purpose and one purpose only - killing other human beings," Biden said that evening in November 1993. "Or we can vote to take these deadly military-style assault weapons off our streets. The choice is that simple. The choice is that stark."

Later that night, after a vote showed a majority of senators wanted to add an assault weapons ban to the bill, he looked at his Republican colleagues and offered a modest taunt: "Why not lose gracefully?"

The assault weapons ban eventually passed, ushering in a dramatic change in the nation's firearms laws and punctuating a years-long effort from Biden to enact gun control legislation. It would prove to be a seminal moment in his long legislative career, and would help cement his views of how the halting machinery of Congress can address the toughest problems of American society.

But nearly three decades later, as Biden attempts to resurrect that approach and puts an assault weapon ban at the center of his rallying cry on guns, the landscape is radically different. The ban he helped pass expired after 10 years and has never been renewed. As president, Biden is confronting the realities of a Congress that operates much differently and a political dynamic that makes the goal almost impossible to achieve.

Even Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., who with Biden led the effort to include the ban in the sweeping 1994 crime bill, is not focusing on a restoration. Instead, she has advocated for a new bill raising the minimum age for the purchase of assault weapons and high-capacity magazines from 18 to 21.

"You know how I feel about this," Feinstein said after news broke of a shooting in Texas that killed 19 children and two adults. "Every [mass shooting] is sort of like a knife in me because I want people to be safe, and I want people to use these weapons appropriately, and they don't." But as for an assault weapons ban, she added, "Whether we have enough support to do something about it, I don't know."

Untraceable “ghost guns” recovered by police on display in Washington, D.C., in February 2020. (Astrid Riecken for The Washington Post )

But Biden, as he has in the past, has quickly embraced the assault weapons ban as a necessary solution. "It makes no sense to be able to purchase something that can fire up to 300 rounds," he said on Monday. "The idea of these high-caliber weapons - there's simply no rational basis for it in terms of self-protection, hunting."

During his prime-time address on mass killings Thursday night, the president mentioned it first in a string of urgent proposals. "Why in God's name should an ordinary citizen be able to purchase an assault weapon that holds 30-round magazines that let mass shooters fire hundreds of bullets in a matter of minutes?" he said.

Biden's focus on the improbable ban is in part a way to rally Democrats on a powerful issue for the upcoming midterms, while depicting Republicans as so unreasonable they refuse to ban killing machines. And in his Thursday speech, he emphasized that if Congress would not ban the weapons altogether, it should at a minimum take more modest steps.

Adam Eisgrau, a former Feinstein aide closely involved in the ban's adoption, said it was "critical and entirely appropriate" for Biden to discuss his legislative aspirations. "It's not puffery, it's not superfluous," he said. "That's what it means to lead. It means to have a vision and to articulate it, even when you don't see a path to achieving it."

But Biden's push for the ban also reflects how he sometimes reaches into the past, to a very time when the parties were far more willing to compromise, as he struggles to confront the crises that rock American during his presidency.

It was back in 1989 that a disturbed drifter wielding an AK-47 variant killed five children and wounded 30 more people outside a Stockton, Calif., elementary school. That prompted two Democratic senators, Dennis DeConcini of Arizona and Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio, to draft the first bills singling out military-style rifles for regulation.

Their bills never passed, but a more opportune moment came four years later, when another horrific shooting handed a platform to a rookie senator. On July 1, 1993, a failed entrepreneur walked into a downtown San Francisco office building armed with a variant of the TEC-9 semiautomatic pistol. He took the elevator and entered the offices of a law firm, where he proceeded to kill eight and wound six more before killing himself.

"This happened in our own front yard," Feinstein told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2003. "It really moved me that we had to do something."

Biden, then chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was helping newly-elected President Bill Clinton push a sweeping crime bill at the time, and Feinstein fought to make an assault weapons ban a part of it. That meant making concessions to skeptics, including an agreement to "sunset" the ban after 10 years so researchers could judge whether it had made a difference.

Debate was heated, but ultimately cordial in a way that reflects how much politics have changed.

Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who co-wrote the crime bill with Biden, warned that inserting the assault weapons ban could prompt opponents to torpedo the entire bipartisan package. "We could stop, it seems to me, the most important crime bill in history," he said.

Biden, though, called his bluff, predicting Republicans were not "going to bring down a $21 billion bill because the NRA does not like it."

A climatic moment came as Sen. Larry Craig, R-Idaho, one of the Senate's staunchest gun-rights proponents, said Feinstein "needs to become a little more familiar with firearms and their deadly characteristics" as he argued against the ban. Feinstein interjected to remind Craig of the 1978 assassination of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, when Feinstein was the first to find Milk's body and found herself announcing the killings to a horrified public. "I know something about what firearms can do," she said.

Biden turned out to be correct: Republicans chose not to filibuster the sprawling crime bill over the gun ban, and Feinstein's amendment was incorporated into the crime bill on a 56-43 vote.

In the House, Judiciary Chairman Jack Brooks, a Texas Democrat, firmly opposed the ban, but a key House Republican, Rep. Henry Hyde of Illinois, helped push it through. When Clinton signed the crime bill into law on Sept. 13, 1994, Biden was among those standing behind him, and it seemed a triumphant moment.

But two months later, rebellious Republicans led by Rep. Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., seized control of the House for the first time in nearly four decades - in part by mocking the crime bill as too soft - and American politics changed for good.

Today in the Senate, the filibuster is deployed much more routinely, and the freewheeling amendment process that allowed the assault weapons ban to pass is now unheard of. Amendment votes, if they happen at all, are meticulously negotiated between party leaders due to filibuster threats.

"We are not in an age of relationship politics. We are in an age of macro-messaging and polarization politics, and that's a big difference," Eisgrau said.

That shift was evident by the time the ban expired: A 2004 amendment to reauthorize the ban won 52 votes in the Senate, including 10 Republicans, but its adoption prompted the NRA to change its position on underlying bill, causing it to fail on 90-8 vote.

As gun rights increasingly become a cultural touchstone on the right, support for the ban has continued to erode. After a gunman killed 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, a proposed ban garnered just 40 votes in the Senate, with 15 Democrats being among the "no" votes.

Of those 15, five remain in office and eight others have been replaced by Republicans who embrace gun rights. That has kept an assault weapons ban almost completely out of the legislative conversations since last month's mass killing in Uvalde, Texas.

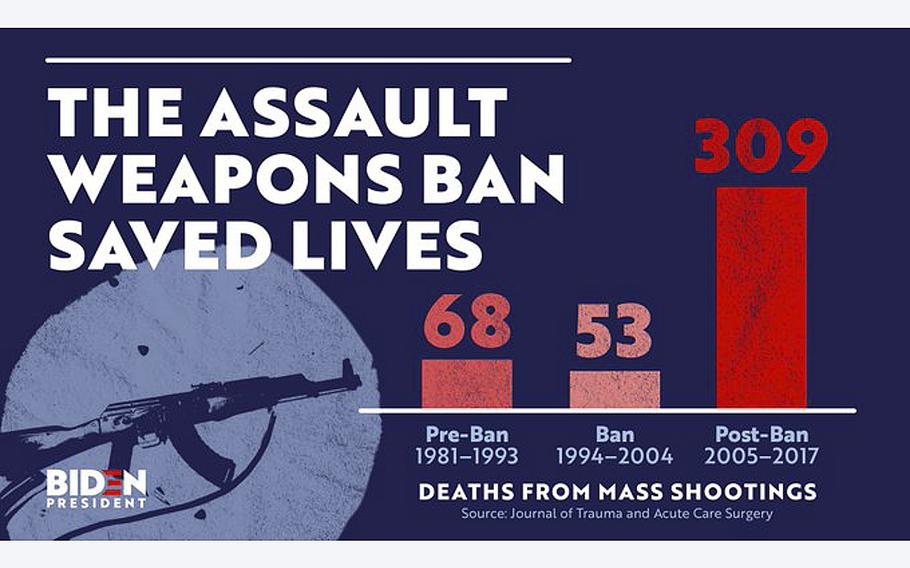

At the same time, advocates and opponents are engaged in a fierce debate about whether an assault weapon ban would accomplish much. The 1994 law banned the sale not only of assault weapons, but also large-capacity magazines that hold more than 10 rounds. Because it had a number of loopholes and was in place for only 10 years, its full impact was initially difficult to measure.

A 2004 study for the Justice Department, for example, found that assault weapons were "rarely used" in gun crimes, but concluded that the law might have had a bigger impact had it remained in place for longer.

Christopher S. Koper, author of that study and an associate professor of criminology at George Mason University, has done research since then suggesting that mass killings increased after the assault weapons ban expired. He wrote in a 2020 study that the restrictions on large-capacity magazines were critical in reducing mass shooting deaths.

The Washington Post Fact Checker, analyzing a Biden comment last year that the assault weapons ban reduced such deaths, found that research increasingly suggests that to be true.

Biden has called the ban on assault weapons ban the toughest deal that has worked on successfully, and as president, he has brought up the notion of reenacting it nearly every month.

"We can ban assault weapons and high-capacity magazines in this country once again," he said in March 2021 after a shooting in Boulder, Colo. "I got that done when I was a senator. It passed. It was law for the longest time, and it brought down these mass killings. We should do it again."

He mentioned it again in his first address to Congress. "Talk to most responsible gun owners and hunters," he said. "They'll tell you there's no possible justification for having a hundred rounds in a weapon."

And he has returned to it again following the tragedy in Uvalde. "What in God's name do you need an assault weapon for except to kill someone?" he said after the shooting, turning to a line he's used since the early 1990s: "Deer aren't running through the forest with Kevlar vests on, for God's sake. It's just sick."

Biden's advisers note that the first assault weapons ban came only after years of debate. The president knows it may not be resurrected in the latest round of negotiations, they suggest, but believes that by emphasizing it he can nonetheless help pave the way.

Republicans, meanwhile, show little unease in defending the right of Americans to purchase military-type rifles. Many have seized upon the weaknesses of the 1994 ban, which struggled to precisely define what constituted an assault rifle. Standard hunting rifles, for instance, share the key attributes of assault rifles - semiautomatic fire of rounds from a detachable magazine - leaving lawmakers and regulators to focus on largely cosmetic traits to distinguish between the two.

"These [bans] all sound very good until you actually get into the practical side of it," said Sen. Mike Rounds, R-S.D. "It's not that we are trying to defend individuals that have evil intent. What we're trying to say is there are millions and millions of individuals that purchase these systems without evil intent."

Two Republican aides familiar with the talks underway in the Senate, speaking on the condition of anonymity to frankly describe their parameters, said any discussion of an assault weapons ban would be a nonstarter. More probable are provisions focused on keeping guns away from those who might harm themselves or others, they said.

The lead Democratic negotiator, Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut, has acknowledged as much.

"We probably can't get a universal background check bill. We probably can't get the votes for a ban on assault weapons," Murphy said last week on the PBS News Hour. "But maybe we can do some smaller things to at least show parents and kids in this country that we take seriously the fear, the anxiousness that they labor under every single day in their classrooms and at home."

Even some White House officials concede that an assault weapons ban is less likely than other measures such as red flag laws and enhanced background checks. But the issue could prove to be a powerful rallying cry ahead of the midterm elections.

"For a while if they didn't think they had the votes, they wouldn't talk about something, and that didn't really serve them well," said Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster who worked on Biden's 2020 presidential campaign. "They are now visibly showing they want to take action - and who is responsible for not taking action? It's members of Congress, and particularly Republican member of Congress."

In hindsight, Lake and others said, the coalition that Biden helped build in 1994 proved crucial to offsetting the powerful opposition. The assault weapons ban was supported by not just gun control advocates, but also by hunters and sportsmen, as well as police officers who were increasingly concerned about being outgunned in the drug wars.

That alliance is gone, at least for now. "Senator Biden built and maintained a coalition that broke through the usual gun control impasse in '94," said Chris Putala, a longtime Biden staffer who worked on the legislation. "We've now got the public attention and anger. The question is whether you can stitch together the kind of coalition that moves people past the obstinate 'do-nothing' minority."