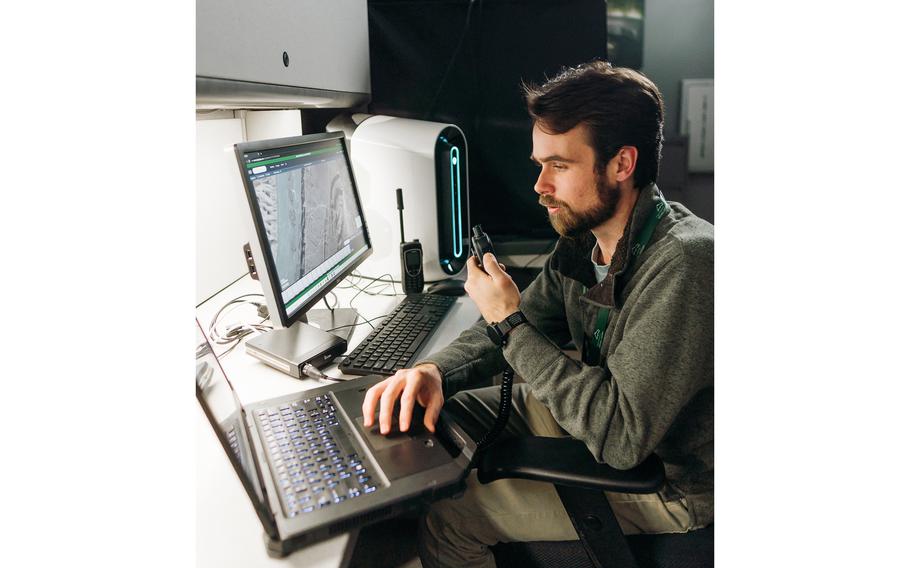

Hayden Bassett inside the Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab at the Virginia Museum of Natural History. (Virginia Museum of Natural History)

In the southwest corner of rural Virginia, about 5,000 miles from the war zone, a small but mighty team of archaeologists, historians and high-tech mapping experts are using sophisticated satellite imagery to help to protect Ukraine's cultural heritage.

Housed in the Virginia Museum of Natural History, the Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab is the museum world's version of a war room: a network of computers, satellite feeds and phones that represents one of the newest tools being employed to protect national treasures threatened by natural disasters or geopolitical events.

Created last year in partnership with the Smithsonian Institution Cultural Rescue Initiative - a world leader in this field - the lab is compiling imagery of Ukraine's cultural sites to help track attacks on them. The goal is to quickly alert officials in Ukraine of damage, in case action can be taken - perhaps to protect artifacts exposed to the elements, or to board up stained-glass windows in the wake of a direct hit on a church - and to document the devastation.

"It's a 24/7 operation," director and archaeologist Hayden Bassett said, adding that the staff of six has been working 12 and 18 hours at a stretch to maintain their rapid response. "Even though we might not be staring at a screen at 3 a.m., our satellites are imaging at 3 a.m."

Using their database of 26,000 cultural heritage sites - including historic architecture, cultural institutions such as museums and archives, houses of worship and places of archaeological significance - Bassett and his team of art historians, analysts and techies have identified several hundred potential impacts in the conflict's first few weeks.

As the world watches Ukrainians sandbagging their statues, boarding up historic structures and moving valuable artwork underground, Bassett is scouring the landscape to rapidly identify the latest targets.

"We can do something right now, with the methods we built, the lab we built, to get information to the people who need it most," Bassett said.

The imaging lab is part of a network of trained museum and archaeological professionals all over the world who have mobilized to help their colleagues under attack in Ukraine, said Corine Wegener, director of the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative. The Smithsonian office is the nerve center for a network of dozens of organizations, including the Prince Claus Fund, a nongovernmental cultural organization in the Netherlands; the International Council of Museums in Paris; the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; and many museums and museum workers in Europe.

"So far, it's mainly teaching materials and advice. Not much can be done as the bombing continues," Wegener said of her office's early interventions. "We are asking our colleagues 'What do you need?' We are trying to coordinate efforts . . . sitting down and saying, 'Here's what we can commit. What do you have?' "

Museum leaders in Ukraine are grateful, said Ihor Poshyvailo, director of the Maidan Museum in Kyiv, who co-founded the Heritage Emergency Response Initiative to organize the local rescue effort.

"We do feel the support of the international community on different levels. International organizations like UNESCO, ICOM [International Council of Museums], Blue Shield and separate institutions," said Poshyvailo, who is on ICOM's Disaster Risk Management Committee. "I have friends from different museums and, on an individual level, people are trying to help."

For example, Metropolitan Museum of Art conservators made smartphone videos for museum workers in Ukraine that demonstrate basic techniques used to pack priceless artifacts for transport or to wrap them in place. (The majority of museum conservators are women, and many in Ukraine have been evacuated, leaving other museum workers to pick up their tasks.) Elsewhere, tech wizards are archiving websites and digital assets to counter Russian cyberattacks. Others are playing matchmaker, connecting museums in Europe that might have storage space with Ukrainian institutions whose collections are vulnerable, or trucks with supplies that can be sent to the front lines. Another focus is securing the country's digital cultural assets: scholarly research, archives and collections data, among other things.

"You don't want to lose that research, or collections databases," Wegener said about helping to move them to cloud-based storage.

The Met is one of the many institutions that works with the Smithsonian on this effort. The museum doesn't have a team of experts on par with Wegener and her crew, but its commitment to protect world culture is just as strong, said Lisa Pilosi, the Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge, Objects Conservation.

As a member of the International Council of Museums' Disaster Risk Management Committee, Pilosi has participated in meetings to help Ukraine.

"So much mobilization is going on around the world," Pilosi said. "It's not easy. There are international organizations and communications exist, but the best thing we can do is help the colleagues we know tap into these existing networks."

Everyone is anxious to help, but it is still early in the process. UNESCO has yet to release an official list of organizations who are assisting. Funds are coming for supplies, and trucks are lining up to transport them. It's hard to balance the desire to contribute with the patience to wait until the aid is most useful.

"The Blue Shield is active, Prince Claus has sent funds to various places," Pilosi said, referring to the international network committed to protecting cultural sites around the world. "The challenge is to asses what is already happening and not to duplicate efforts.

"We have to take our proper place in the overall response," she added, noting that humanitarian aid remains the top priority. "Our strength is going to be in the longer-term recovery."

The Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, born during the institution's response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, has become the field's leader by training museum workers around the world in crisis preparation and response and providing resources and marshaling support in places such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. Some individuals in Ukraine that they are communicating with, including Poshyvailo, have gone through their training, Wegener said.

Poshyvailo adapted the Smithsonian emergency response training for his Ukraine institutions and has used its policies for the Heritage Emergency Rescue Initiative. They have surveyed museums and other institutions, asking what they need and for evidence of cultural property being lost or damaged, he said.

"We tried to think strategically, not only about urgent needs, but what action will be needed tomorrow and the day after tomorrow," he said.

Now in Lviv, he is working to support the Ministry of Culture in creating an inventory of cultural institutions and collections, while responding to reports of damage around the country. Many of the reports are difficult to confirm because of ongoing violence, he said.

Wegener and others were advising Ukraine museums to protect their collections, which he said was difficult to do in advance. "It can cause panic," he said, "and the general political message was we should prepare only on a military level."

The data and photographic documentation from the VMNH lab will be useful in the future, he said. He and others in Ukraine are compiling a similar list. "It's very primitive," he said. "This will be very helpful."

Crimea and Ukraine were an early focus of the monitoring lab because of the ongoing conflict there, said Damian Koropeckyj, who started last April as senior analyst and team lead for Ukraine.

"We wanted to look there first to see if cultural heritage was being impacted during what I would describe as a warm conflict," he said.

His early research found examples of monuments destroyed by the fighting were being replaced by new ones supporting Russian and its version of the area's cultural heritage. That led to the larger project of creating an inventory for the entire country, an initiative that became more important as the potential of a Russian invasion grew.

"We're a remote project. But it's certainly very real to me. Believing we can make a difference here is important," Koropeckyj said.

Since the invasion last month, the lab has tracked artillery and other military strikes using satellite sensors, including infrared technology, matching the impacts against the lab's mapped cultural heritage inventory. If a strike seems close to a site, they pull satellite images or, through the Smithsonian, direct a satellite to capture images of the area.

Speed is critical, even at this stage, Bassett said. As an example, he posed a scenario of a museum taking a direct hit. "If there's a giant hole in the roof, you're now exposed to the elements. During this short period, we've seen snowfall and other weather events. Imagine it's snowing into a museum," he said. "You're also exposed to security concerns, exposed to looting. And the building is now vulnerable to further deterioration.

"It is basically on the clock for further damage," he said. "We can assist in immediate identification, and minimize the time to response. That's one of the more pragmatic reasons" for the work.

The documentation has long-term value, too, Wegener said. The military action that is damaging Ukraine's cultural heritage violates the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, known as the 1954 Hague Convention. Both Russia and Ukraine signed the UNESCO treaty, and therefore, are responsible for protecting cultural sites, art and books and scientific collections.

"It can be used for legal accountability," Wegener said about the visual documentation. "We are working on documentation to show crimes against them."