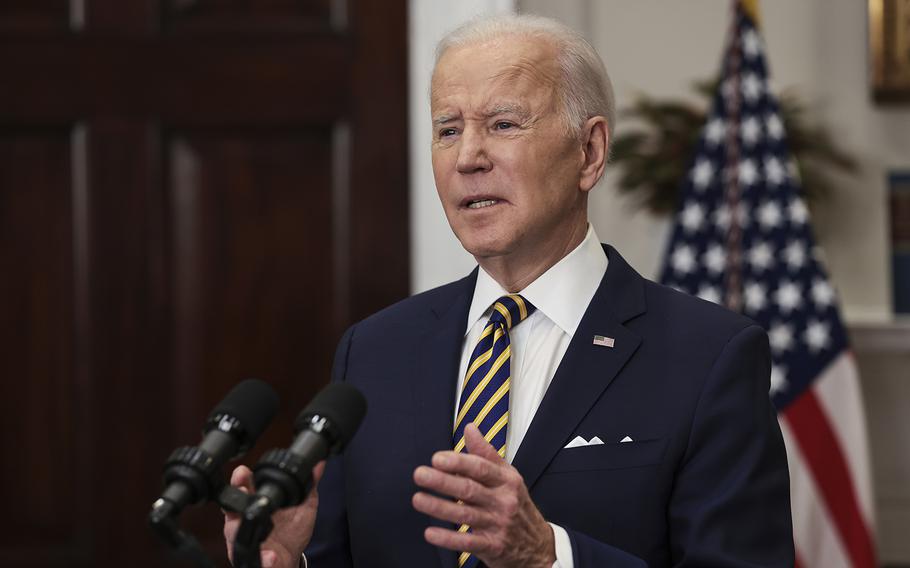

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House March 8, 2022, in Washington, D.C. During his remarks, Biden announced a full ban on imports of Russian oil and energy products as an additional step in holding Russia accountable for its invasion of Ukraine. (Win McNamee/Getty Images/TNS)

Back in 2016, U.S. officials waited months to officially blame Russia for trying to influence the election by hacking Democrats’ emails.

Now researchers are urging the government to move a lot faster in the 2022 and 2024 elections to release any information it might garner about potential Russian cyber and disinformation campaigns.

The goal is to subvert Kremlin plans, blunt the force of any hack and release operations and help guard against American voters being taken in by phony claims during an election cycle.

It’s modeled on a rapid declassification of intelligence on Russia’s Ukraine invasion, which was widely celebrated by analysts who said it blunted Russian efforts to justify the invasion and helped strengthen U.S. allies’ opposition.

“There’s a recognition, especially when the public imagination is the target, that there’s more that can be done to blunt those efforts,” Gavin Wilde, a former Russian-focused National Security Council official, told The Washington Post.

Wilde, who’s now a managing consultant at the Krebs Stamos Group, co-authored a paper with Justin Sherman, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, that advocated for such intelligence declassification.

--In 2016

The traditional hesitancy to declassify and release intelligence has often worked against U.S. interests - especially where Russia’s concerned.

That hesitancy has usually been driven by concern about giving the adversary a heads up about how U.S. intelligence agencies are getting their information. But it’s also made it easier for Russian information operations to have a greater impact, including by influencing U.S. public opinion.

For example: It wasn’t until October 2016 that the U.S. government officially blamed Russia for hacking and leaking emails from the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign - months after the emails had been released online and begun to sway public opinion.

Some information about Russian hacking operations in the election didn’t come out until the release of the Mueller report in 2018. Per that report, Kremlin hackers breached voter rolls in at least two states before the 2016 contest, but there’s no evidence they changed any votes.

--Ukraine war

The government moved much faster when it came to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Biden administration took a novel approach to Russia, rapidly declassifying and releasing intelligence about the Kremlin’s invasion plans and phony justifications for the operation.

The move to release information in advance of the Ukraine invasion was widely celebrated by analysts who said it blunted Russian efforts to justify the invasion and helped strengthen U.S. allies’ opposition.

“In 2016, you had an effort by Obama and [Director of National Intelligence James] Clapper to say, ‘let’s get all of our cards on the table,’ but it was still a post hoc diagnosis. Whereas, this time there’s clearly political will at the senior levels to bless getting out ahead [of Russian operations],” Wilde told The Post.

--Looking ahead

U.S. officials have been trying to learn the lessons of 2016. When Iran launched an operation to sow fear and doubts around the 2020 election, officials rapidly exposed details of the operation. That scheme involved posing as the Proud Boys, a far-right group, and threatening violence against registered Democrats if they didn’t vote for President Donald Trump.

There’s no evidence of major interference by the Kremlin in the 2020 presidential election. But such interference may be more likely in 2022 and 2024 given U.S.-Russia tensions following the Ukraine invasion and a spate of punishing U.S. sanctions

Lawmakers are increasingly concerned that Russian President Vladimir Putin will turn to election interference as a way to retaliate against the United States for harsh sanctions, as Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., told The Post recently.

The status of Ukraine has also frequently been a topic in Russian disinformation campaigns targeting the West.

“A common theme from 2016 onward is that Ukraine’s trajectory is a motivating factor for Russian influence efforts against U.S. elections,” Wilde said. I would certainly bet on 2024 being another trial run for some of these operations, so we should steel ourselves.”