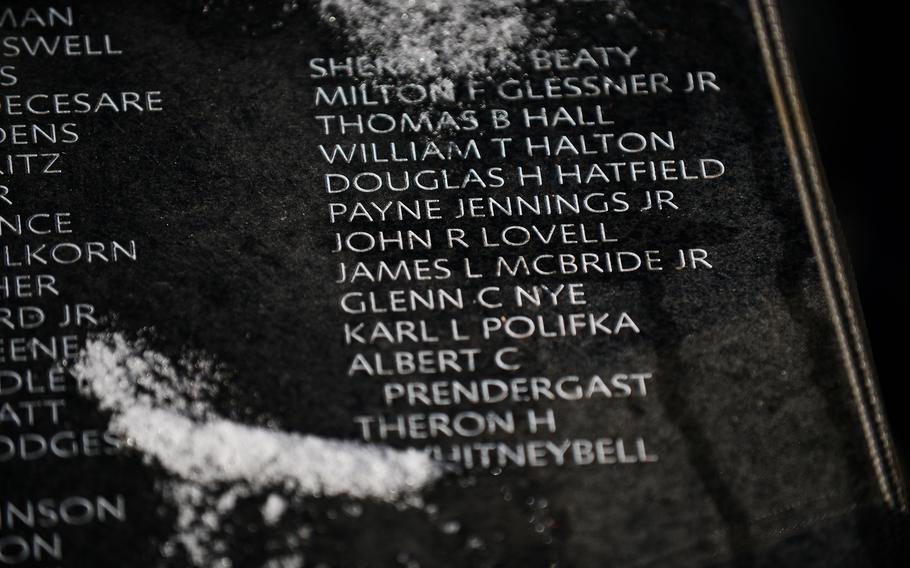

The first seven-ton panel with 450 names was placed at the Korean War Memorial early Monday. Col. John R. Lovell’s grandson was there to watch. (Astrid Riecken/Washington Post)

WASHINGTON — After the seven-ton granite block was uncrated, and the huge yellow crane had lowered it into place, workers brushed off the snow and Richard Dean walked over to look at his grandfather’s name.

“John R Lovell,” was carved in the last column of names, six from the bottom, under the heading, Colonel. He had been shot down on an intelligence mission during the Korean War. His body has never been found.

“I’m without words,” Dean, 62, said this week at the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington. “It’s been a very long time . . . And [I’m] honored to see my grandfather’s name. It’s his resting spot for right now.”

Lovell, who was killed in December 1950, is among the first of 43,000 Americans and Koreans in the U.S. service whose names are now being recorded in stone at the haunting memorial on the National Mall.

The huge block, bearing his and about 400 other names, was put into place shortly before 11 a.m. Monday on a bright but frigid morning. It had arrived by truck and was dusted with snow from the Minnesota quarrying site where it was fabricated.

Stone workers with measuring and surveying devices swarmed around it, and gave hand signals to the crane operator to make sure it was correctly placed.

Dean, in a brown hard hat, blue jeans and yellow jacket, looked on. “You’re making history today, guys,” he said.

A retired Army colonel who grew up in Wheaton, Md., he is the unpaid volunteer construction management agent for the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation, and a member of the foundation’s board.

He was also the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project engineer when the memorial was constructed in the mid-1990s.

“I have a lot of history with this memorial,” he said.

“I feel overwhelmed sometimes,” Dean said. “I feel honored to be able to pay homage to the veterans . . . It’s from the heart . . . I’ve been deployed a few times, to Kosovo and Afghanistan. I know what war’s like. And I know what these guys went through.”

“When this memorial was actually being built, the veterans would come up and say ‘Where are the names of my buddies?’ “ he said. He thought they were referring to the nearby Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which lists the names 58,000 Vietnam War dead.

No, he said they told him, they meant their pals from Korea. He said there had not been enough room.

No more. Last March, officials announced that the memorial would be getting a Wall of Remembrance, like the Vietnam wall, to commemorate those who died in the Korean War.

And it was just by chance of logistics that the first block to be placed Monday bore his grandfather’s name, Dean said.

Lovell’s reconnaissance jet, an RB-45C, was shot down by enemy aircraft on Dec. 4, 1950, near the border between China and North Korea, according to the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Dean said he believes his grandfather survived the crash, but was captured and “stoned to death” by enraged North Korean civilians egged on by his captors, based on research information gathered by his mother.

The block was the first of 100 that are being added to the site in an extensive overhaul of the 26-year-old landmark just southeast of the Lincoln Memorial. The project, which got underway in March, is scheduled to be finished by July.

The National Park Service and the memorial’s foundation have said that the blocks will include the names of 36,574 Americans and more than 7,200 Koreans, who served as advisers and interpreters in what was called the Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army (KATUSA).

But first the Pentagon had to come up with a list of names - a fraught task.

“The first names that were verified were [those from] the Marines, the Navy and the Air Force,” Dean said. They appear on 16 thinner stone panels that are being put in place this week. Each one contains about 450 names, he said.

They include the decorated Air Force pilot Maj. Felix Asla Jr. He was shot down Aug. 1, 1952, in “MiG Alley,” an area over North Korea infested with Russian-built MiG fighters flown by the enemy. His body has never been recovered.

And Col. Theron H. Whitneybell who was killed when his jet ran out gas and crashed while he was returning from a combat mission on Nov. 13, 1950. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Also, Air Force Capt. John H. Zimmerlee Jr., who had served during World War II, and had nearly been killed when the bomber he was on was brought down in the Adriatic Sea, said his son, John P. Zimmerlee.

Plucked from the water, seemingly dead, by a rescue ship, he was being readied for a burial when someone noticed that he was still alive, his son said in a recent interview.

When the Korean War broke out, he was married with two children, but was still called up.

A navigator, he was one of five men aboard a B-26 bomber on a mission on March 21, 1952. “They went out in the evening and didn’t come back,” his son said. They apparently ran into bad weather and radioed another plane.

“That was the last communication they had with anybody else,” he said. “No one has really described what their mission was all about.” His father’s body has never been recovered.

“The whole thing is really disgusting,” he said.

Regarding the memorial’s names project, he said: “It’s nice that whoever is funding this is honoring our guys. And I do appreciate that. But as a family member I really would prefer to get the information on what actually happened” to his father.

The panels listing the Army’s dead are far more numerous and are still being worked on, Dean said: “There’s roughly 27 panels that will be Army privates, and about 29 panels will be PFCs.”

Funding for the $22 million project comes from donations from the people of the United States and South Korea, the Park Service and the memorial foundation have said.

Part of the work required the installation of 178 underground pilings drilled more than 50 feet down to bedrock to support a section of the memorial that had sunk about three inches, Dean said.

The memorial’s 19 stainless steel statues depicting an American patrol during the war have been refurbished. And lighting has been improved.

The Korean War (1950-1953), was fought between forces of the United States, South Korea and their allies, and forces of communist North Korea and China.

It was a bitter, back-and-forth struggle that killed people on the ground and in the air. It claimed more than half as many Americans in three years as the Vietnam War killed in over a decade.

Thousands fell during fighting in subzero temperatures around the Chosin Reservoir, in what is now North Korea. And U.S. pilots were shot down in many forbidding places, like MiG Alley near the Chinese border.

Seven thousand Americans are still missing in action.

On Monday, as the workers finished up their measurements and declared that the placement of the first block was correct, a foreman stepped back and called out: “Ninety-nine to go!”