WASHINGTON — CIA Director William Burns delivered a confidential warning to Russia's top intelligence services that they will face "consequences" if they are behind the string of mysterious health incidents known as "Havana Syndrome" afflicting U.S. diplomats and spies around the world, according to U.S. officials familiar with the exchange.

During a visit to Moscow earlier this month, Burns raised the issue with the leadership of Russia's Federal Security Service, the FSB, and the country's Foreign Intelligence Service, the SVR. He told them that causing U.S. personnel and their family members to suffer severe brain damage and other debilitating ailments would go beyond the bounds of acceptable behavior for a "professional intelligence service," said the officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss highly sensitive conversations.

The warning did not assign blame for what U.S. officials are calling "anomalous health incidents," or AHIs. The fact that Burns formulated the warning by saying "if" suggests that after four years of investigations across multiple administrations, the U.S. government remains unable to determine a cause of the unusual incidents. Nevertheless, the director's decision to raise the possibility of Russian involvement directly to his counterparts in Moscow underscored the deep suspicion the CIA has of Kremlin culpability.

The CIA declined to comment on Burns' warning to the Russians, which has not been previously reported. The Russian Embassy in Washington did not respond to requests for comment.

Moscow has previously denied any involvement in the Havana Syndrome incidents, a phenomenon named after the Cuban capital where U.S. diplomats and intelligence officers first reported unusual and varied symptoms — from headaches and vision problems to dizziness and brain injuries — that started in 2016.

The main purpose of Burns' trip to Moscow was to put the Kremlin on notice that Washington was watching its troop buildup on the border of Ukraine and would not tolerate a military attack on the country, officials said.

His appearance in Moscow at the behest of President Joe Biden was designed to convey Washington's seriousness. The CIA chief — a former deputy secretary of state and ambassador to Russia — has handled some of the president's most sensitive missions, including senior-level engagement with the Taliban after its takeover of Afghanistan.

The inability to determine a cause of the health incidents has rankled members of Congress and infuriated the U.S. diplomats and intelligence officials who say they suffer from the affliction.

The Biden administration has sought to demonstrate that it is taking the cases seriously and has encouraged employees across the federal government to report any potential health issues they may be experiencing. In recent months, two senior U.S. officials were replaced after being accused of failing to take the incidents seriously enough: the CIA station chief in Vienna, where dozens of U.S. spies and diplomats have reported AHIs, and Ambassador Pamela Spratlen, the State Department's top official overseeing Havana Syndrome cases.

After Spratlen's exit, Secretary of State Antony Blinken appointed Jonathan Moore, a career diplomat, to head the Health Incident Response Task Force and another senior Foreign Service officer, Margaret Uyehara, to ensure that those affected by the ailment receive medical care.

Burns has publicly described the incidents as "attacks," and some U.S. officials suspect they are the work of Russian operatives. Other officials have attributed them to a psychogenic illness experienced by individuals working in a high-stress environment. Those blaming Russia speculate that it could be using energy weapons to sicken U.S. personnel. Others have noted that there is scant evidence connecting the use of energy weapons to the symptoms reported.

In July, Burns placed a senior CIA officer who played a leading role in the hunt for Osama bin Laden in charge of the task force investigating the cause of the illnesses.

In August, two U.S. employees in Hanoi reported symptoms just before Vice President Kamala Harris arrived in the Vietnamese capital on an official diplomatic trip. The diagnoses delayed her visit by a few hours.

In September, an intelligence officer traveling with Burns in India reported symptoms of Havana Syndrome and required medical attention, current and former officials said. Some saw that incident as a message to CIA leaders that they, too, can be targeted anywhere.

More than 200 health incidents have been reported around the world in the past five years, on every continent except Antarctica, yet there is no clear pattern explaining them. In some cases, U.S. employees have reported symptoms related to Havana Syndrome but upon further diagnosis the ailments were attributed to other factors, said a senior administration official.

The mysterious incidents prompted rare bipartisan support behind the Havana Act, a bill Biden signed into law last month that creates a federal program to compensate U.S. diplomats, intelligence officers and other officials who have suffered traumatic brain injuries associated with Havana Syndrome.

"We are bringing to bear the full resources of the U.S. government to make available first-class medical care to those affected and to get to the bottom of these incidents, including to determine the cause and who is responsible," Biden said at the signing.

The Havana Syndrome mystery adds another layer of complexity to the U.S.-Russia relationship as the Biden administration tries to determine whether Moscow's buildup of troops along the border with Ukraine is muscle-flexing or the preamble to a full-scale invasion of the country.

The administration is seeking to de-escalate the situation amid calls from Republicans to send more military aid to Ukraine.

"We're not sure exactly what Mr. Putin is up to," Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said last week

The past several weeks have seen a flurry of diplomatic contacts among U.S., Russian and Ukrainian officials. Besides Burns' discussions with FSB and SVR officials, he also phoned Russian President Vladimir Putin while in Moscow and met with the head of Russia's national security council, Nikolai Patrushev. Blinken met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the sidelines of the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, this month, and a senior State Department official was recently dispatched to Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital.

The Washington Post's Shane Harris contributed to this report.

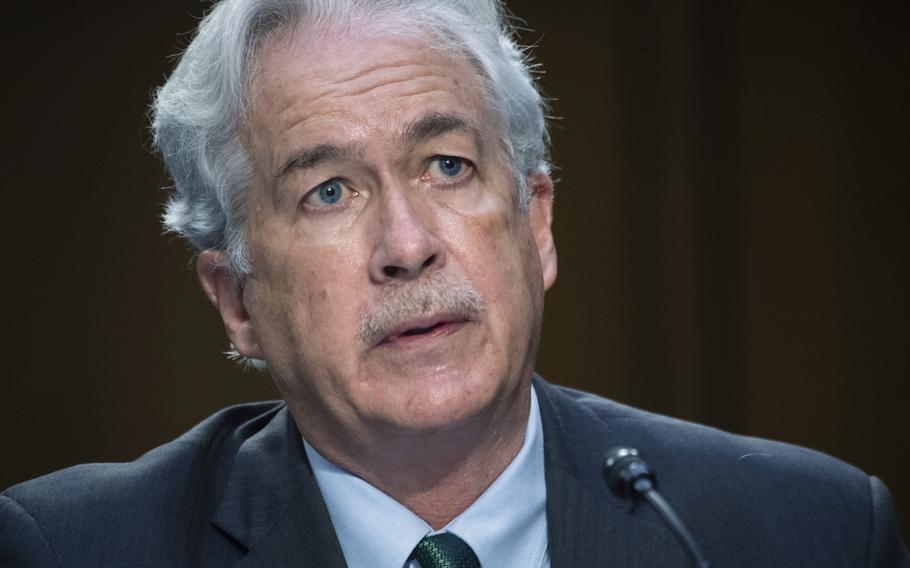

CIA Director William Burns testifies during a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence hearing about worldwide threats, on Capitol Hill in Washington, April 14, 2021. (Saul Loeb/Pool via AP)