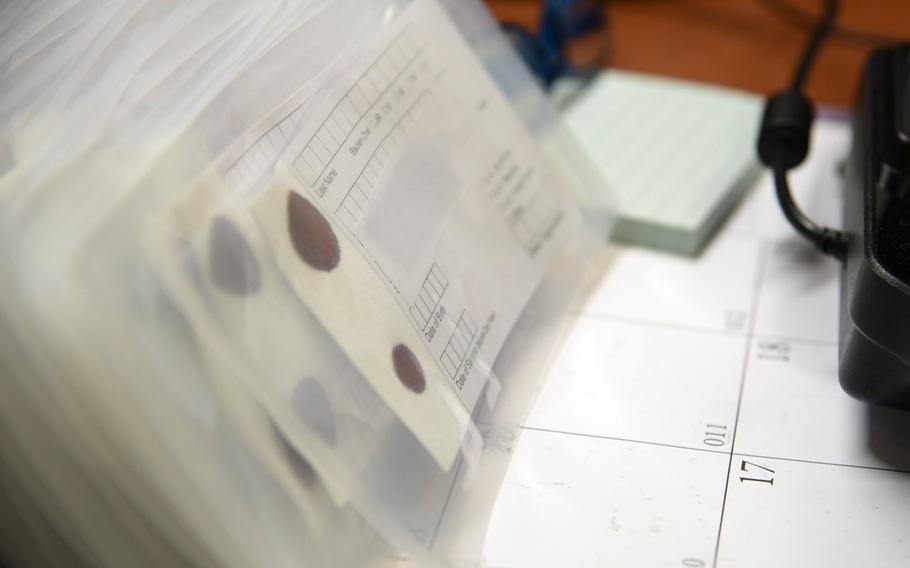

A worker removes a container of blood-sample cards at the Armed Forces Repository of Specimen Samples for the Identification of Remains at Dover Air Force Base, Del., Jan. 30, 2019. (Dedan Dials/U.S. Air Force)

Twenty-three years ago, then-Defense Secretary William Cohen publicly pondered whether any American warfighter would ever again need to be buried as an unidentifiable “unknown.”

Cohen’s rumination came after DNA testing conclusively identified the remains lying in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier for the Vietnam War as 1st Lt. Michael Blassie, a 24-year-old Air Force flyer shot down May 11, 1972, in South Vietnam.

"It may be that forensic science has reached a point where there will be no other unknowns in any war,” Cohen told reporters during a Pentagon briefing on June 30, 1998.

“I could be proven wrong, but it would seem to me that given the state of the art today, it's unlikely that we'll have future unknowns,” he said.

Blood-sample cards sit on a desk at the Armed Forces Repository of Specimen Samples for the Identification of Remains at Dover Air Force Base, Del., Jan. 30, 2019. (Dedan Dials/U.S. Air Force)

Almost a quarter-century later, DNA technology has only gotten better, and no American service member killed in action over the past 30 years has been buried as unknown.

But could today’s forensic science succeed in the aftermath of a conflict such as World War II, a cataclysm out of which the remains of roughly 8,500 American troops were recovered but deemed unidentifiable?

“Yes and no,” said Josh Hyman, director of the DNA sequencing facility at the University of Wisconsin’s Biotechnology Center.

“I say yes because the technology is capable of giving us pretty good detail on a genetic level,” he said during a phone interview Oct. 28.

Add to that, he said, the Defense Department maintains blood samples taken from inductees into the armed forces over the past 25 years that can be used for flawless DNA comparisons.

“The reason I say probably no is because in a lot of situations it’s not that you can't identify something coming from a bone or a tooth,” he said. “It's just that — especially in World War II — you had mass graves and things got mixed. We have a lot of bones in our body. The difficulty back then and now is that if you ever have a mass grave, if you ever have a mixture and you don't have any way of definitively separating them out to begin with, well, it's simply not feasible to test every single bone to make a decision.

“You try and assemble things and do your best. You have to have someone who can look at the physical bones and say, yeah, these seem to belong together and then you can start testing and test a number of them.”

DNA misconceptions

Forensic anthropologist Denise To agrees, touting the advances in DNA technology while offering up similar caveats.

“One of the common misconceptions is that DNA is the end-all be-all of all identifications,” said To, who manages the forensic laboratory for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, during a phone interview Oct. 27.

“It's not that simple,” she said. “It's complex enough that we require multiple lines of evidence to make an identification, such as dental evidence, forensic anthropology, forensic archaeology.”

Today’s capacity to identify American war dead stands atop a painful history.

“At Arlington, there are over 4,000 unknown soldiers from the Civil War,” said Philip Bigler, a former historian at Arlington National Cemetery and author of “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier: A Century of Honor” published in 2019.

Fighters from both North and South sometimes carried little in the way of identification, often not even wearing a uniform or insignia, Bigler said during a phone interview Oct. 19.

“If you were killed on the battlefield, you had a pretty good chance of not being identified during the Civil War, just by the nature of the combat,” he said.

U.S. warfighters first began wearing metal identification tags during World War I, a practice that became uniform and widespread during World War II when they were dubbed dog tags.

“But even that system is not particularly foolproof because we have many examples of people holding dog tags in their pockets of either fallen individuals or even living individuals,” To said.

In 2009, the lab identified the remains of a World War I soldier who was in possession of dog tags belonging to a fellow soldier who had survived the war and lived until 1972, she said.

Safeguarding medical records

Thorough medical recordkeeping, including detailed dental diagrams and X-rays, were maintained on the vast number of service members during World War II. Those records have been invaluable in identifying unknowns from that war, but they also revealed a weakness in relying on such documentation.

In July 1973, fire broke out at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, which held millions of official military files spanning the 20th century. The massive blaze destroyed the records of about 18 million veterans, including roughly 80% of Army personnel discharged between 1912 and 1960 and 75% of Air Force personnel discharged between 1947 and 1964.

“We learned the lesson that, forensically, you want to keep medical records better,” To said.

DNA identification technology emerged in the late 1980s.

In a nutshell, the method compares unique DNA markers in an individual with that of a close relative or descendant. In some cases it is compared to a database of individuals.

The key to the method’s success, then, is procuring that comparable sample, but when no relative can be found, the DNA test is of little use.

For example, DPAA recently concluded a multiyear project to exhume and identify 388 sailors and Marines buried as unknowns from the battleship USS Oklahoma, which was destroyed during the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

The agency identified many of the remains — which had been badly burned and commingled — through DNA testing. But a handful are slated to be buried once again as unknowns next month because in some cases comparative samples from next of kin could not be found.

Game-changing collection

Congress moved to fix that shortcoming in 1992 by mandating the collection of blood samples from incoming service members. The collection’s sole purpose is to maintain “self-reference” DNA samples that will exactly match that of any service member who dies on the battlefield.

As of early 2019, the Armed Forces Repository of Specimen Samples for the Identification of Remains at Dover Air Force Base, Del., held almost 8 million blood samples taken from inductees into the armed services over the past 25 years. The index cards carrying two splotches of blood are vacuum sealed and held for 50 years.

“Identifying the deceased with a self-reference is superior to identifying the deceased through DNA with a comparative sample to a relative,” To said. “The self-reference is really important to us, and it is a game-changer in terms of identifying individuals who die now in combat in our wars.”

The samples were used to positively identify more than 800 service members who died during Operation Enduring Freedom, the Defense Department said in a 2019 news release.

Still, even DNA science could be stymied by unidentified remains under certain circumstances in future wars.

“For example, right now, we can't really obtain DNA sequences from samples that are heavily burned,” To said. “Fire destroys DNA so there could be some remains that have been thermally altered where the DNA cannot be extracted.”

Hyman said that even badly burned bodies yield some DNA samples, particularly from the teeth.

“But it's true that if you incinerate things at certain temperatures, then all you have is ash,” he said. “There’s nothing there to get. I mean, at that point, there aren’t any remains, only ashes.”