Army Chief of Staff Gen. Raymond T. Odierno, center, with Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey and White House Chief of Staff Denis McDonough before a White House ceremony in 2013. (LEO SHANE III/Stars and Stripes)

Raymond Odierno, a four-star Army general who was a key architect of the “surge” in U.S. forces during the Iraq War that was credited with reducing violence and increasing stability in the country and who later became the Army’s chief of staff, or highest-ranking general, died Oct. 8 at age 67.

His death was confirmed by Lt. Col. Terence Kelly, an Army spokesman, who announced that cause was cancer. Further details were not immediately available.

An imposing figure, at 6-5 and 250 pounds, with a shaved head, Gen. Odierno had an affable nature and developed a strong rapport with his troops. He was considered one of the Army’s most capable battlefield leaders.

He had three tours of duty in Iraq from 2003 to 2010, culminating in his being named the chief commander of all Allied forces in the country. Units of Odierno’s 4th Infantry Division pulled off perhaps the signature moment of the Iraq War when they tracked down and captured Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein on Dec. 13, 2003.

After the heavily bearded and unkempt Hussein was found in an underground bunker in a rural area north of Baghdad, Odierno uttered one of the more memorable comments of the conflict: “He was just caught like a rat. When you’re in the bottom of a hole, you can’t fight back.”

Hussein was later convicted by an Iraqi tribunal of crimes against humanity, and he was executed in December 2006.

Despite the high-profile capture of Hussein, Odierno had a mixed record during his first tour in Iraq. Soon after his arrival in the country in 2003, he told those under his command: “I want to make sure you understand my intent: that I want to be lethal. Make them understand, when they come up against us, they’re going to be killed or captured.”

The 4th Infantry Division became known for its rough methods, including breaking down the doors of private homes and grabbing young Iraqi men off the street and delivering them to the notorious Abu Ghraib prison.

“Odierno’s brigades and battalions earned a reputation for being overly aggressive,” journalist and military historian Thomas Ricks wrote in “Fiasco,” his 2006 book about the early stages of the Iraq War. “Again and again, internal Army reports and commanders in interviews said that [the 4th Infantry Division] used ham-fisted approaches that may have appeared to pacify its area in the short term, but in the process alienated large parts of the population.”

Odierno said the Army had a dual mission in Iraq that was almost impossible to achieve.

“Half the time you spend rebuilding the country,” he said in 2003. “And the other half of the time you spend figuring out how you’re going to destroy the insurgency — and they’re diametrically opposed.”

- - -

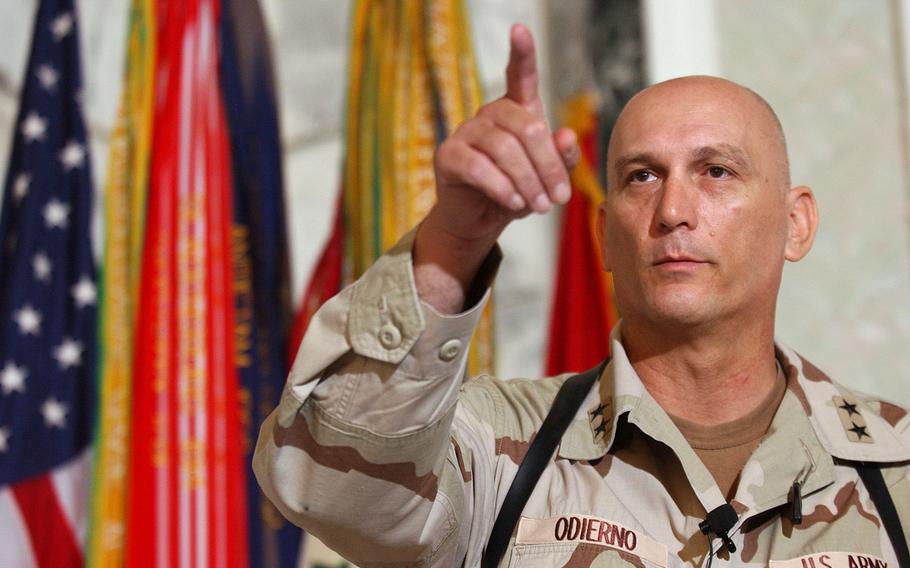

In this Aug. 7, 2003 file photo, Major Gen. Raymond Odierno, commander of the U.S. Army Fourth Infantry Division gestures during a news conference in Tikrit, about 112 miles northwest of Baghdad, Iraq. Odierno, a retired Army general who commanded American and coalition forces in Iraq at the height of the war and capped a 39-year career by serving as the Army’s chief of staff, has died, his family said Saturday, Oct. 9, 2021. He was 67. (Dario Lopez-Mills/AP)

Odierno returned to Iraq for a second tour of duty in 2006, this time as the Army’s second-ranking general, after David Petraeus. Military observers said he seemed to have learned a lesson from his early experiences. He adopted a less confrontational style, they said, and made a great effort to understand the Iraqi people and their needs.

“I’m convinced he went through a complete metamorphosis,” retired Army Gen. Jack Keane told the Los Angeles Times in 2008. “He educated himself and became the very best operational commander we have in conducting irregular warfare.”

Odierno’s thinking was also affected by his son’s experience in Iraq. In 2004, a rocket-propelled grenade hit a Humvee in which Anthony Odierno, a young Army officer, was riding. The driver beside him was killed, and Anthony Odierno’s left arm had to be amputated.

“It didn’t affect me as a military officer, I mean that,” Odierno told The Washington Post a few years after the incident. “It affected me as a person.”

“That drives me, frankly,” he added. “I feel an obligation to mothers and fathers. Maybe I understand it better because it happened to me.”

Odierno also recognized that standard military strategies had failed to contain Iraq’s guerrilla insurgency. From 2004 to 2006, attacks on U.S. forces increased, and Iraq seemed about to spiral into civil war between Sunni and Shiite Muslims — with the Americans caught in the middle.

At the time, the prevailing thinking in the Pentagon was that the 140,000 U.S. troops on the ground would be enough to maintain order. Odierno was among the few active-duty military officers to call for a rapid deployment of about 20,000 more troops — the surge, as it was called — to help quell the Iraqi insurgency.

The move was opposed by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Vice President Dick Cheney and national security adviser Stephen Hadley supported the troop surge. It was also endorsed by Keane, who was retired but had the ear of influential White House officials — and was in constant touch with Odierno.

In the end, President George W. Bush approved the idea and asked a new defense secretary, Robert Gates, to implement the plan after Rumsfeld was ousted in late 2006.

Odierno took charge of the surge operation in Iraq, deploying additional troops to secure the perimeter around Baghdad and to slow the movement of insurgents. There was a new emphasis on building trust with the Iraqi people.

“It was about getting out among the population,” Odierno told TV interviewer Charlie Rose in 2013. “It was about us understanding that we had to be out there with the Iraqis and with the Iraqi army and police to make them feel comfortable, that they felt secure . . . And it enabled us then to conduct . . . targeted operations on only those individuals that were leading and conducting the violence inside of Iraq.”

The surge was deemed a success at the time, as the number of killings of Iraqi civilians and U.S. troops fell dramatically. A measure of social stability began to take root, but the long-term effectiveness of the strategy remains a contested issue among military historians and other observers.

Odierno received his fourth star, becoming a full general, in 2008, the year he replaced Petraeus as chief commander of the multinational force in Iraq. The United States was reducing its presence in the country, and by the end of 2011, most U.S. troops had been withdrawn.

“If Petraeus . . . was the public face of the troop buildup, he was only its adoptive parent,” Ricks wrote in The Post in 2009. “It was Odierno . . . who was the surge’s true father.”

In 2011, Odierno was named the Army’s top general. As a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he advised the president and Congress and helped shape the country’s military planning. As Army chief of staff, he oversaw the withdrawal from Iraq and the continuing conflict in Afghanistan, and he addressed other issues facing the military, including suicide and sexual assault.

He also saw that some of the progress he had made in Iraq was beginning to unravel. “It’s disappointing to all of us to see the deterioration of the security inside of Iraq,” he said in 2014. “I believe we left it a place where it was capable to move forward.”

- - -

Lt. Gen. Raymond Odierno, commander of Multi-National Corps-Iraq, speaks with a group of local sheiks at Patrol Base Kemple, Dec. 18, 2007. Odierno, a four-star Army general who was a key architect of the “surge” in U.S. forces during the Iraq War that was credited with reducing violence and increasing stability in the country and who later became the Army’s chief of staff, died Oct. 8, 2021, at age 67. (Curt Cashour/Department of Defense)

Raymond Thomas Odierno was born Sept. 8, 1954, in Rockaway Township, N.J. His father, an Army sergeant during World War II, was an engineer. His mother was a receptionist in a medical office.

Odierno was a star high school player in football, basketball and baseball. He went on to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., where his main athletic ambition was to play tight end on the football team. Knee injuries cut short his gridiron career after two years, but he was a standout pitcher on Army’s baseball team, with a 5-0 won-loss record in his senior year.

After graduating in 1976, Odierno became an artillery officer. He received a master’s degree in nuclear effects engineering from North Carolina State University in 1986 and a second master’s degree, in national security and strategic studies, from the Naval War College in 1990.

At first, Odierno planned to fulfill the five-year active-duty obligation of all U.S. Military Academy graduates and then enter civilian life. But he came to enjoy the Army, in part because he found camaraderie and sense of purpose similar to what he experienced in sports.

He served in the Persian Gulf War in 1991, had overseas assignments in Germany and Albania, and was the primary military adviser to Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice during the Bush administration.

Odierno retired from the Army in 2015. His decorations included four Defense Distinguished Service Medals, two Army Distinguished Service Medals, the Defense Superior Service Medal, six awards of the Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star Medal.

In retirement, he became an adviser to JPMorgan Chase, and he was named chairman of USA Football, which promotes youth football, and chairman of the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League. He was also a member of the College Football Playoff Selection Committee. He lived in recent years in Pinehurst, N.C.

Survivors include his wife of 45 years, the former Linda Burkarth; three children; a sister; and four grandchildren.

Odierno never lost interest in Army sports and often stood on the sideline at football games, sometimes joining in players’ huddles. In 2012, when he was chief of staff, he addressed the Army football team before a game against service-academy rival Air Force. A former Army football player, John “J.T.” Thomson, now a retired three-star general, was in the locker room that day. After Odierno’s inspiring pregame speech, Army rolled past Air Force, 41-21.

“This was 27 years after my last game,” Thomson later said, “and I was ready to strap on a helmet and play.”