The military's system of allowing juries to determine sentences at courts-martial may end under legislation in Congress supported by the Pentagon, advocates say. The proposal would require military judges to determine sentences using guidelines. (Donna L. Burnett/U.S. Air Force)

Court-martial sentencing by juries may go the way of flogging, a change many military justice experts say is long overdue.

Military judges instead would hand down sentences based on federal guidelines as part of military justice system reforms proposed in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act. The act isn’t expected to be signed into law until sometime after the new fiscal year starts Friday.

The proposal is supported by the Pentagon and is included in both the House and Senate versions of the legislation.

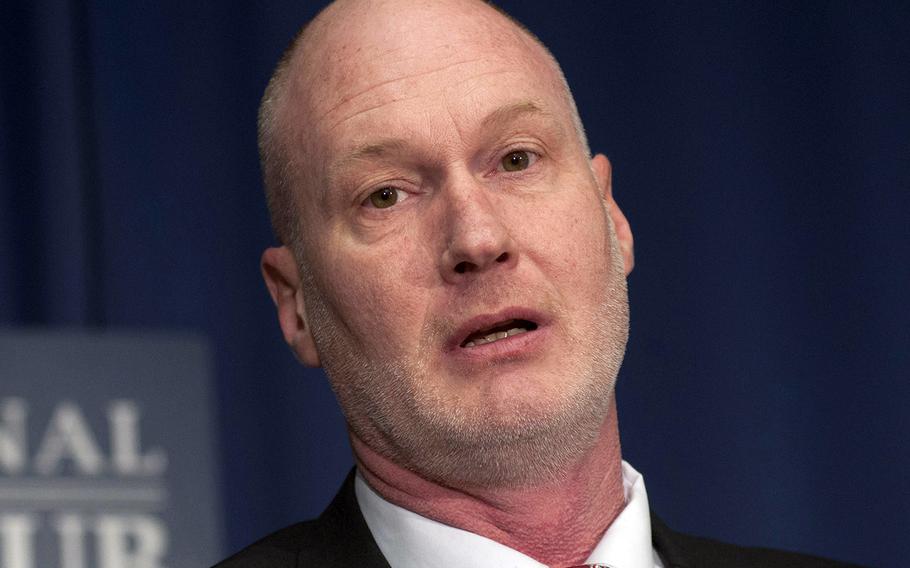

"I'm confident the sentencing portion will survive," said Don Christensen, a former Air Force prosecutor and president of Protect Our Defenders, an advocacy group for military sexual assault survivors.

Don Christensen, a former Air Force prosecutor and president of Protect Our Defenders, an advocacy group for military sexual assault survivors, says sentencing in military courts is inconsistent. (JoeGromelski/Stars and Stripes)

Supporters say the revision would make sentences in military trials fairer, as well as more consistent and predictable.

“People convicted of sexual assault, one guy gets five years, the other guy gets no confinement,” Christensen said. “In drug cases, you’d also see huge disparities with no justification. With shaken baby cases, sentences were all over the place.”

Military defendants currently may choose whether a judge or a jury, called a “panel,” decides their cases, including sentencing.

Military jurors have little experience, context or guidance when determining sentences, Christensen said. That is magnified by the fact that under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, jurors’ sentences can range from no punishment all the way to lengthy prison terms, he added.

The system also allows for “compromise” verdicts, in which jurors agree to a guilty verdict in exchange for little or no punishment, Cmdr. Justin McEwen, a Navy judge advocate, argued in an undated paper titled “Moving Towards Uniformity in Sentencing at Courts Martial.”

“Every year, accused Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines are sentenced to vastly different punishments for the same offenses based on virtually identical facts,” McEwan wrote. “These results cause many to question the fairness of a system that would allow for such disparities in sentences.”

Earlier this year, the findings of an independent Pentagon board that reviews military sexual assault illustrated the inconsistencies in sentencing between the two formats.

Military judges sentenced defendants to confinement in 83.7% of sexual assault convictions, while panels of military members sentenced a defendant to confinement only 63% of the time, the commission determined.

“Astoundingly, victims of sexual assault offenses where members handled punishment saw their perpetrator walk freely out of court in 37 percent of all cases, despite a conviction,” the commission found.

Only a handful of states still allow jury sentencing, which has been called “sanctified guessing,” “sentencing by lottery,” a “crapshoot” and “amateur brain surgery” in various legal papers.

Proposals to end it in the military date to at least 1983. The Pentagon proposed an overhaul in 2016, but the idea was dropped.

However, traditionalists argue that jury sentencing allows military communities to be involved in the justice system and define their own punishment norms while balancing operational needs and military discipline.

“The panel is in the best position to come up with a fair and just sentence because they are familiar with the requirements of justice and the requirements of military discipline,” Dru Brenner-Beck, a former Army lawyer who now practices law in Colorado, told Stars and Stripes. “People need to look at the existing system rather than say civilian good, military bad.”