Soldiers assigned to Bravo Troop, 1st Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Division strap a soldier with a simulated injury to a litter during an exercise in Hohenfels, Germany, April 12, 2015. StatBond, a gel developed with military funding, may allow medics to stop arterial bleeding without the need for compression, Army Research Laboratory officials said May 4, 2021. (Brian Chaney/U.S. Army)

Military-funded researchers are developing a gel that would stop rapid blood loss without the need to apply pressure to a wound, which could potentially save lives on the battlefield and in civilian hospitals.

Medics can apply coagulants like QuikClot to wounds to stem blood loss long enough for a service member to get to a field hospital. But arterial wounds can be hard to treat in the field, said Robert Mantz, a chemistry branch chief with the Army Research Laboratory.

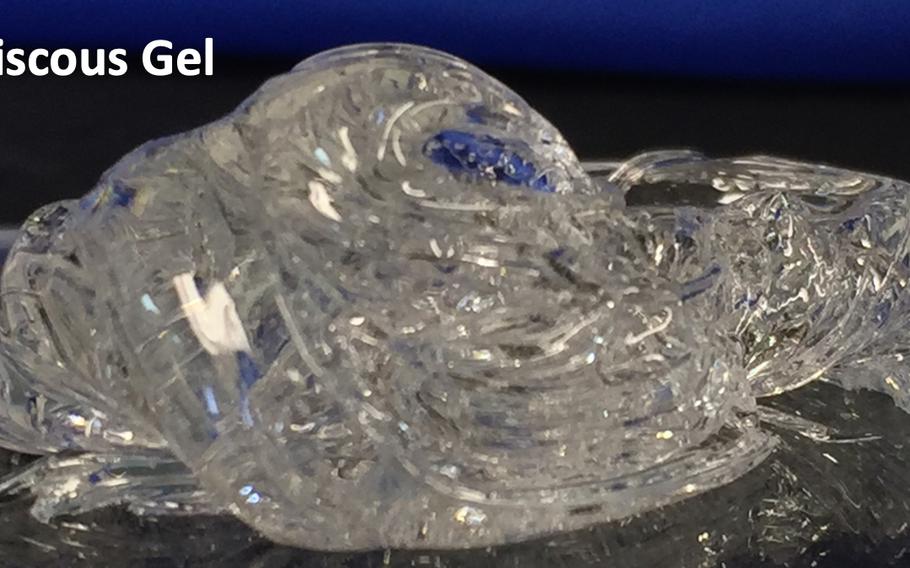

Troops dying from blood loss to parts of the body where bandages or tourniquets can’t be applied has been a persistent problem during battles of the past two decades. The researchers say that StatBond, a clear, silicon-based gel, may help.

StatBond, a gel developed with military funding, may allow medics to stop arterial bleeding without the need for compression, Army Research Laboratory officials said May 4, 2021. (U.S. Army)

“The thing that excites me about this is that we have data that shows this works on an arterial bleed, and to my knowledge, none of the other products out there can handle that,” Mantz said on the phone Tuesday.

Blood pulsing out from arterial wounds can wash away coagulants before they can stem the bleeding, unless someone stays to apply pressure, which medics under fire may not always be able to do. Wounded fighters handed over for transport also may not have someone available to apply pressure.

The Defense Health Agency has funded the research into StatBond, which is applied using something like a caulking gun.

The hemostatic gel flows into the wound and seals it, allowing leaking blood vessels to clot, an Army statement said. The gel could be placed into areas such as the groin, trunk, armpit, neck, internal organs and eyes.

The research was conducted by the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Vanderbilt University and the Nashville, Tenn.-based Ichor Sciences.

Similar products such as WoundStat have been pulled from use by the Army due to issues with safety.

StatBond, a gel developed with military funding, may allow medics to stop arterial bleeding without the need for compression, Army Research Laboratory officials said May 4, 2021. (U.S. Army)

Animal testing hasn’t found any negative reactions to StatBond, Mantz said, adding that the gel does not chemically react, generate heat or harden. It can be left in the body and flush out over time naturally.

The gel is going through registration with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and human testing may begin soon, Mantz said.

The product may be available to physicians by next year and to soldiers by 2025 if testing goes well, said Joe Lichtenhan, vice president of technology for Hybrid Plastics, a Mississippi-based nanotechnology company involved in the research.