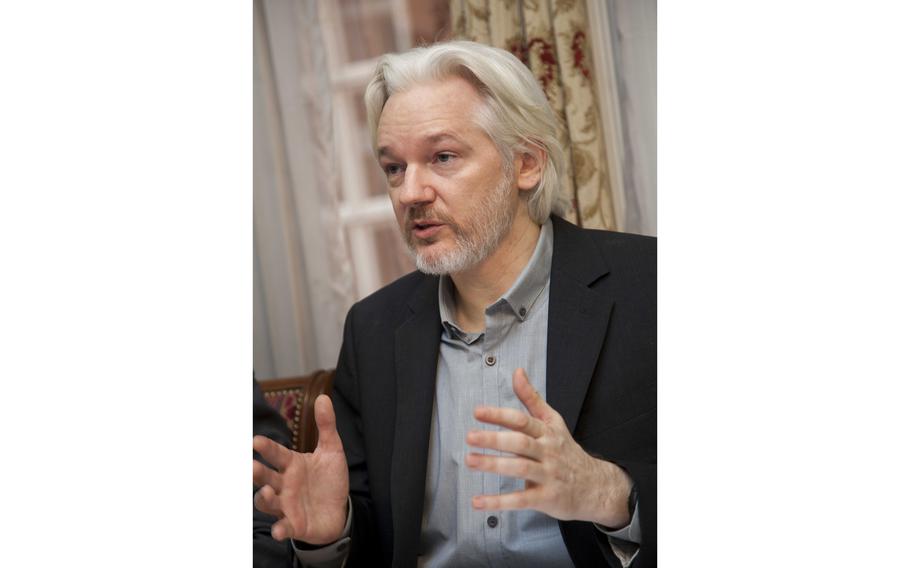

Julian Assange (David G Silvers/Wikimedia Commons)

LONDON — Should he be convicted of espionage in Virginia federal court, the United States has offered that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange could serve his sentence in Australia, a British court said Wednesday.

The assurance came as the Justice Department seeks to extradite Assange from London, where he is currently in custody.

A judge in Britain blocked his transfer to the United States in January, ruling that he was at extreme risk of suicide and might not be protected from harming himself in a federal prison.

Now, the United States has been granted an appeal before Britain's High Court, on the grounds that the lower-court judge did not hear assurances of how Assange would be treated in American custody.

According to the High Court, the United States consented to transferring Assange to his native country of Australia to serve any prison sentence. Should he serve time in a U.S. facility, the government pledged that Assange would not be held in total isolation or imprisoned at a "Supermax" facility in Colorado.

No date has been set for the hearing. The United States could also argue that the lower-court judge misapplied extradition law in how she weighed Assange's health.

The 50-year-old Australian publisher and hacktivist remains in London's Belmarsh prison, where he has been held since the Ecuadoran Embassy in London revoked his political asylum two years ago. He spent almost seven years in a few cramped rooms at the embassy before he was arrested by British police for jumping bail.

In the United States, Assange is charged with 18 federal crimes, including conspiring to obtain and disclose classified diplomatic cables and sensitive military reports from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

His lawyers and supporters say he is a journalist who did nothing more than publish leaked information that embarrassed the U.S. government.

His former lawyer and fiancee, Stella Moris, said she had spoken with Assange on Wednesday about the ruling that the U.S. appeal can go forward.

Moris, who has two young children with Assange, called the case "an endless purgatory."

"We don't how long this will go for and how long he will be imprisoned for in that terrible place," she told SBS News in Australia.

Moris has pleaded, first to President Donald Trump and now President Joe Biden, to drop the case.

Under Biden, the Justice Department has pledged to stop seizing journalists' communications in leak investigations and to hold accountable Capitol rioters who attacked members of the media.

But the administration has continued the case against Assange, who prosecutors say crossed the line from publisher to conspirator.

Former WikiLeaks associate Sigurdur Thordarson gave an interview last month saying he lied to U.S. investigators when claiming to have stolen information from Icelandic politicians, police and a bank.

WikiLeaks supporters, including Edward Snowden, have argued that the interview undermines the criminal case against Assange. But the Icelandic article, which contains no direct quotes from Thordarson, does not touch on the core allegations against Assange.

In the indictment, Thordarson's claims are used not as the basis for charges but as background for what Assange told Chelsea Manning, who as an Army soldier exposed classified information through WikiLeaks in 2010.

Thordarson in the article also does not deny involvement in the hacking of U.S. targets, and tells the publication his activities were "something Assange was aware of or that he had interpreted it so that this was expected of him."

In blocking his extradition in January, British District Judge Vanessa Baraitser said she had no doubt Assange could get a fair trial with an impartial jury in the United States.

Instead, she focused on evidence presented by Assange's legal team that their client suffered from severe depression, had written a will and had sought absolution from a priest, and that a razor blade was found hidden in his cell.

She said that if Assange were convicted of espionage, he could be sent to a federal supermax prison, the Administrative Maximum Facility in Florence, Colo., a facility where some inmates are kept in lockdown 23 hours a day with almost no human contact.

Baraitser said from the bench, "I am satisfied the procedures described by the U.S. will not prevent Mr. Assange from finding a way to commit suicide."

In a subsequent hearing, Baraitser refused to grant Assange bail and release him from British prison, noting that the appeal process was not over and Assange "still has an incentive to abscond."

Nick Vamos, a former head of extraditions for the Crown Prosecution Service and now a partner at the law firm Peters & Peters in London, said, "I don't know why this appeal is taking so long."

He said it was possible that behind the scenes lawyers for Assange, the Crown Prosecution Service and the U.S. government might have been negotiating charges or conditions of his confinement.

When the High Court does hear the U.S. appeal, the session could take a day or two. Even then, it may not be over. The losing side could make a further appeal to Britain's version of the Supreme Court.