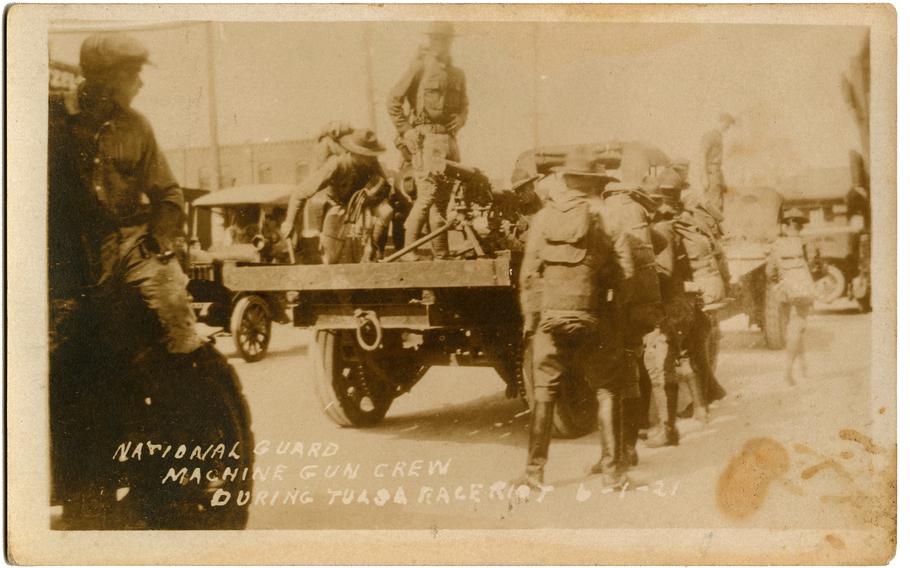

This black-and-white photographic postcard titled "National Guard Machine Gun Crew" shows a group of soldiers marching through Tulsa on June 1, 1921. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

He liked to call himself "Diamond Dick."

Dick Rowland, a tall teenager with velvet skin, wore a diamond ring as he shined shoes in downtown Tulsa. Rowland, 19, had recently dropped out of Booker T. Washington High School, where he was a star football player, because he was making so much money polishing the shoes of oil men in a city that billed itself as the "oil capital of the world."

On May 30, 1921, Rowland took a break from his shoe stand inside a pool hall and walked to the Drexel Building to use the only public restroom for Black people in segregated Tulsa.

Rowland passed Renberg's, a department store that occupied the first two floors of the Drexel Building, and stepped into a open wire-caged elevator operated by a 17-year-old white girl named Sarah Page.

What happened next remains murky, according to historians and reports about one of the worst episodes of racial violence in U.S. history. Rowland may have accidentally stepped on Page's foot, prompting her to shriek. Or tripped and bumped into her.

When the elevator doors reopened, Dick Rowland ran, and a clerk in Renberg's called police.

Rowland was arrested and accused of assaulting a white girl. Though the charges were eventually dropped and Page later wrote a letter exonerating him, the accusation was enough to infuriate white Tulsa.

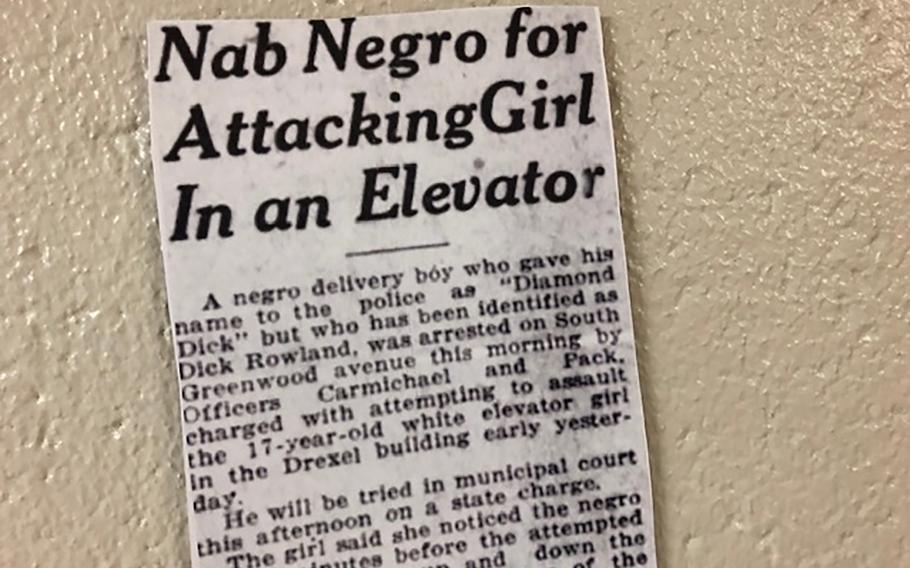

Historians say this 1921 Tulsa newspaper report, with the headline "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator," helped incite the massacre. (DeNeen L. Brown)

Three hours after the Tulsa Tribune hit the street with the headline "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator," hundreds of white men gathered at the Tulsa courthouse, where Rowland was being held.

Black World War I veterans who wanted to protect Rowland from being lynched rushed to the courthouse to defend him. A shot was fired, and "all hell broke loose," a massacre survivor recalled later.

"As the whites moved north, they set fire to practically every building in the African American community, including a dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drug stores, eight doctor's offices, more than two dozen grocery stores, and the Black public library," according to a 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. "By the time the violence ended, the city had been placed under martial law, thousands of Tulsans were being held under armed guard, and the state's second-largest African American community had been burned to the ground."

As many as 300 people were killed, 10,000 were left homeless and 35 square blocks of Greenwood, one of the country's most prosperous Black communities, were destroyed. Witnesses reported seeing bodies tossed into the muddy Arkansas River or dumped into mass graves, making it impossible to count the dead.

While smoke still rose from the ashes of Greenwood, Tulsa's sheriff, Willard McCullough, and his deputy, Barney Cleaver, one of the first Black lawmen in Oklahoma, hustled Dick Rowland out of town.

And Rowland, the central figure in the race massacre, would disappear, adding to the uncertainties that surround the century-old attack.

As Tulsa commemorates the centennial of the massacre this weekend, the city is still haunted by unresolved questions about it: How many people were killed? What happened to the bodies? Who were the white perpetrators? Are there mass graves? And what happened to Dick Rowland?

"It is mysterious because we just don't know (much) about Dick Rowland, the teenager whose arrest was a catalyst for the massacre," said Kristi Williams, an educator and a community organizer in Greenwood.

In Tulsa, Rowland has become almost a mythical figure and a subject of legend and folklore.

"Who is Dick Rowland in history? We know he was a hard-working Black man, whom racists falsely accused," said Black State Rep. Regina Goodwin, D-Okla.

Goodwin said from her research she believes that Sarah Page never accused Rowland of anything. And Page disappeared, too.

Dick Rowland and Sarah Page survive the massacre, "all the pain and the turmoil," Goodwin said, "and they leave Tulsa with not even the smell of smoke on them."

One fact many historians agree upon is Dick Rowland was not his original name.

"He was born Jimmy Jones," around the year 1903, said Marc Carlson, director of special collections at the University of Tulsa's McFarlin Library.

"He and his two sisters were orphans in Vinita," a small Oklahoma town about 60 miles from Tulsa, Carlson said. "They were unofficially adopted by a woman named Damie Ford.

He was probably 3 or 4 years old when she took him in. Ford eventually moved to Tulsa and married Dave Rowland, whose last name is sometimes spelled Roland or Rolland in public records.

A John Roland is listed in the 1920 Census in Tulsa on East Archer Street with Damie Rowland and Dave Rowland. John Roland, historians say, was still a child when he told people he wanted his first name to be Dick.

"He liked the name Diamond Dick, which is what he was calling himself," Carlson said.

Dick Rowland is pictured in the 1921 yearbook for Booker T. Washington High School. "He could have dropped out after picture taken," Carlson said.

Ellouise Cochrane-Price, the daughter of massacre survivor Clarence Rowland and a cousin of Dick Rowland, claims Dick and Sarah not only knew each other before he stepped on the elevator but were in love and were planning to defy Oklahoma's ban on interracial marriage.

"They were planning on getting married," she told an audience at the Oklahoma Black Caucus gala last month. "They had spent many Sundays over my grandma's house, at family dinners.

When the white mob gathered outside the Tulsa courthouse, she said, "the mayor, the sheriff and the marshal were aware that Dick had not attacked Sarah. There had been no attempted rape of any kind. However, that information was not given up or not received by the mob that was gathered to hang Dick Rowland."

In September 1921, the charges against Dick Rowland were dropped, according to records.

Charles Franklin Barrett, the Oklahoma National Guard adjutant general whose troops were called into Tulsa during the rampage, concluded that the massacre was caused by "an impudent Negro, a hysterical girl and a yellow journal."

On Sept. 28, 1921, The Topeka Plain Dealer newspaper reported: "It was brought out in the investigation that he was entirely innocent, the girl never having complained that such were the facts as published in a local WHITE PAPER. Sarah Page has vanished and has never been apprehended since the day she made a statement refuting the charges alleged against Rowland."

Most historians agree that Rowland escaped Tulsa. Where he landed is another story.

Several reports say that Sheriff McCollough took Rowland to Kansas City. But Rowland may have secretly returned to Tulsa in the fall of 1921.

He came to the tent where Damie Rowland was living after her boarding house was burned down in the massacre. "She fed him and they talked some and Dick said he was so sorry, but there were only so many ways he could express his remorse," Tim Madigan wrote in his book "The Burning." "What was done was done, Damie said."

In a 1970 interview with Tulsa historian Ruth Avery, Damie Rowland said he'd asked her about people who died in the massacre and those who survived. He left the tent before dawn.

"He wrote to her every month from Kansas City," Madigan wrote. He told her that Page was in Kansas City, too.

"Dick said that Sarah felt terrible that the police had arrested him for something he didn't do, but she never talked at all about the burning and killing set in motion by her lies," according to Madigan. "If Dick still loved Sarah, he didn't say. "

Then her name disappeared from Dick's letters and not long after that, he moved to Oregon, where he found work in shipyards along the coast.

Damie Rowland told Avery that she continued to receive letters from Dick until the 1960s. Finally, Damie told Avery, she received a letter from a friend of Dick, saying he had been killed in an accident on the wharf.

Carlson said that Rowland may have been killed in an explosion in a port explosion in Oregon.

But Dick Rowland's name does not appear on the list of people killed in that explosion.

"He was probably using a different name altogether," Carlson said. "I suspect when you are in the center of something like this, he was probably terrified to be more public. We have no documentation whatsoever. That's part of the folklore around the whole massacre. There is a lot of stuff we don't know. Unless something concrete shows up, we will never know."