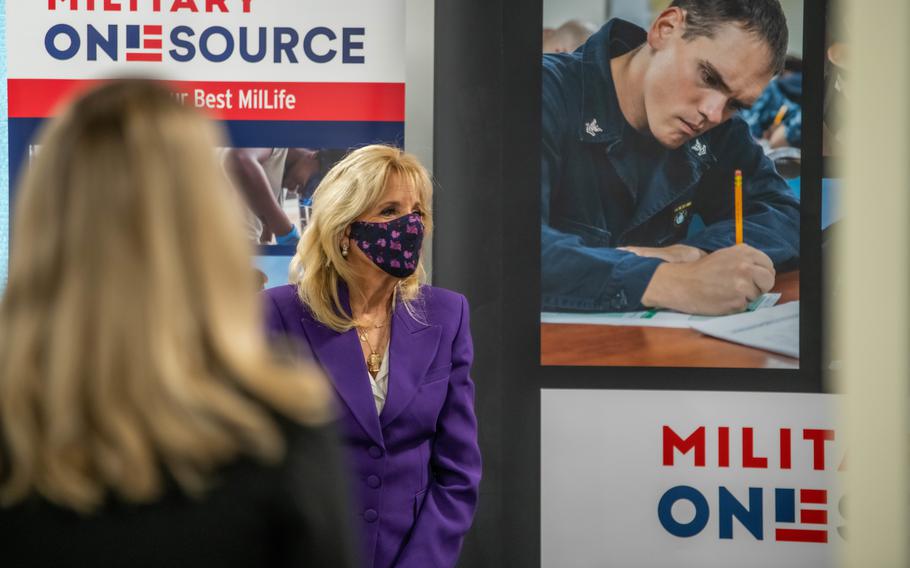

First lady Jill Biden listens to a facilitator from Military OneSource during a facility tour with Charlene Austin and Hollyanne Milley, in Arlington, Va., April 7, 2021. (Jack Sanders/DOD)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more staff and wire stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

For nearly a decade, the unemployment rate for military spouses has sat stubbornly at 22% -- nearly four times higher than the current national average. While the challenges that often block spouses from finding long-term, meaningful employment remain constant, military family advocates believe the coronavirus pandemic may have shifted employers’ perceptions enough on remote work to open the door for real progress.

“Honestly, I think that’s one of the beauties of the pandemic is that it shows just how creative we can get with remote employment,” said Jennifer Davis, government relations deputy director for the National Military Family Association. “I think this is kind of the perfect time and opportunity to just drive that home.”

While acknowledging that the pandemic has devastated overall employment levels, especially among women, which account for 88% of military spouses, the association and other military advocates want to capitalize on the shift that stay-at-home orders have had in accepting remote work as productive and beneficial for a company.

“The pandemic kind of removed the stigma of remote work, because now everybody’s having to figure out a way to make it work,” said Sue Hoppin, founder and president of National Military Spouse Network. “It does work. We can have a geographically dispersed workforce, and still provide a product or service and still work together cohesively.”

A Defense Department survey released in December showed that, despite years of ongoing effort to get more spouses into jobs, the unemployment rate has held at 22% since 2012. The survey, which the department conducts every other year, included responses obtained from more than 65,000 spouses in 2019 – before the pandemic hit.

Meanwhile, advocates are pitching Congress and the Defense Department to implement other measures to provide incentives for companies to hire spouses and improve state partnerships to allow spouses to move more easily with occupational licenses.

“I think we just need to flip the dynamic a little bit and maybe ask different questions,” Hoppin said. “Not what will it take to hire military spouses, but what will it take to retain military spouses who move?”

Inside the Defense Department, Lee Kelley, director of military community support programs, said seeing the statistic remain unchanged in yet another spouse survey was “disheartening.”

“It’s an area that we are focused on every single day,” she said. In fiscal year 2021, the Pentagon directed $65.9 million toward spouse employment programs, which range from career counselors and workshops to developing partnerships with private companies to helping develop state partnerships that ease state licensing requirements for certain careers. The Defense Department also offers qualified spouses $4,000 in tuition assistance to pay for an associate degree, license, certificate program or approved testing that expands employment opportunities.

Given the lessons learned in the pandemic, Kelley said she’s reviewing the department’s existing programs to adapt to “the changing landscape of employment.” She’s actively working to expand an employer-partnership program with more than 500 companies to include more small businesses, which have typically been more hesitant to hire military spouses because the risk of them moving.

“I think we are at a point where companies are recognizing that a military spouse moving actually doesn’t matter at all. They can maintain the training that they’ve invested in that military spouse, the experience that they’ve had and continue to leverage their skills that as they seamlessly transition from one location to another,” Kelley said.

Solving the problem isn’t just about the financial stability of a military family, it is also about readiness, self-worth and emotional well-being, she added.

“The word dependent has such a negative connotation in the military, and military spouses can feel like they lose their identity,” Kelley said.

Adapting goals to job availability

Tatyana Ray, who is married to an Army officer assigned to Peterson Air Force Base, Colo., has felt that loss of identity. Her entire life, she said her parents raised her to do well in school, go to college and get a good job with a high income.

“That definitely hasn’t been my experience, because I married a military service member and we move around so much,” she said

About six years ago, she landed a position with Purdue University Global as a military outreach coordinator, which allows her to work remotely from wherever her husband is assigned. Since then, they’ve moved four times with a fifth scheduled for the summer.

“It definitely takes the stress out of [moving] so frequently,” Ray said. “If I had a different job at all of these installations, I know that there are employers that would look at [my resume] like, ‘What is wrong with you? Why are you changing jobs every year and a half?’”

The consistency of the university outweighs the fact that she’s working outside her intended field. She has a master’s degree in early childhood education and youth development, but faced challenges early in her career when she tried to focus on this field alone.

Ray previously worked as a Defense Department civilian in Child Youth Services, but after each move she struggled to find openings that would help advance her career forward. She didn’t work at all during a year spent in Alabama, because she simply couldn’t find a job. While in Germany, she chose to take a step back in her career, which she said stunted any momentum she’d built to leverage for a better salary in future employment.

“I finished my master’s in Germany, and I was like, I have this master’s and I am sitting at home,” Ray said. “Emotionally it was a blow, and it took a year to kind of get through that because you start to question every choice you’ve made at that point. I made the best of a bad situation, but I’ll tell you those first few months, it was definitely hard.”

To cater to expanding remote work opportunities for spouses, the USO of Metropolitan Washington-Baltimore opened in March a shared workspace at Fort Belvoir, Va., specifically for military spouses who need somewhere to conduct business. It features semi-private space, a conference room, a second-floor patio and office equipment on an appointment basis, said Maura Keenan-Gondek, a program supervisor for the regional USO. They had 50 reservation requests within the first two months with spouses seeking a quiet place to work, study, write resumes or prepare for interviews.

“We know women in the workforce have been really affected by [the coronavirus pandemic] and that they’ve had to make that hard decision to leave employment because they’re managing virtual education of their kids, and the emotional and social health of their children during this time. For some just it’s too much. You can’t do everything,” Keenan-Gondek said. “But having this space gave that spouse an opportunity to be able to tag team with their service member and say, ‘OK, I need to go and get some stuff done and I’m going to go to this quiet workspace.’”

Courtney Reed, an Army spouse, does property management and has used the USO space to work out lease agreements and other business without interruptions from her 6-year-old daughter.

“It’s hard to write a lease when you don’t have a half-hour of uninterrupted time. When I leave the house and actually say the words, ‘I’m going to the office,’ everybody just sort of respects the lingo,” Reed said. “Not to mention the margin of error. I don’t make errors when I’m there because I’m not interrupted.”

Mollie Raymond, spouse of Space Force’s Chief of Space Operations Gen. John “Jay” Raymond, said she toured the USO’s workspace and would love to see it expand to other bases. In connecting with spouses of Air Force and Space Force members, she said employment and self-care remain among their top concerns.

In the fall, the two services will host a virtual forum to discuss spouse employment with an emphasis on using social platforms, such as LinkedIn.

“I’m not looking for work, but I love my LinkedIn connections. I see so much opportunity being offered,” Raymond said. “The more information I have, I think makes me a better advocate and a better connector. A lot of what I like to do is connect spouses to resources, so if I have knowledge, that helps others.”

When remote isn’t possible

Remote work isn’t possible for everyone, and so there is also a push to continue improvements for the 30% of military spouses who work in fields regulated by state occupational licenses, said Davis, of the National Military Family Association.

Licensure compacts, which are meant to remove barriers for spouses in jobs that require a state license, have come a long way, she said. Those fields include health care, teaching, law and real estate. The nursing compact agreement is the largest, with 33 states recognizing a nurse’s credentials from other states in the compact.

“I think more and more [states] are coming around to understanding why this is beneficial for them,” Davis said. “If you’ve got a military family that comes to your local installation and they have a job, that helps with your local economy. It’s just a win-win.”

For instances where no compact is available, the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act allowed each service branch to offer reimbursement up to $1,000 each for spouses who have to renew their licenses in a new state after moving.

Congress and the White House are also renewing efforts, with two bills being refiled this month to include military spouses in the Work Opportunity Tax Credit and the return of the Joining Forces program, under first lady Jill Biden’s direction, that targets several areas of stress in military life.

Hoppin, of National Military Spouse Network, said she is encouraged by the program’s return.

“That did a really great job of bringing more corporate employers to the table to get them to hire military spouses, and then to start the conversation around why we make a really great workforce,” she said. “What we’ve done a really good job of is getting military spouses employed. What we haven’t done a really good job of is keeping a military spouse employed through transitions through [moves]. … Because we have the employers at the table and they’re interested in hiring spouses, what do we need to do to get them to retain spouses?”

Once more spouses start getting into full-time employment, Kelley said Defense Department support programs are ready to help them adjust to the changes that will likely follow in their relationships.

“The way that we look at spouse employment isn’t in a bubble. It isn’t in a silo. It’s related to all the other aspects of well-being and readiness,” Kelley said. “If I connect a spouse with a job, that does not solve all of the challenges that that military spouse may face to be able to get to that job. Now there’s childcare, there’s transportation, there’s the changing roles in the home.”

With so much of a military family’s life intertwined, she said they will continue to seek ways to address the full picture of supporting those who serve.

“We are committed to continuous process improvement, but also continuous learning of the developing environment,” she said.

For more information about the Defense Department’s spouse employment programs, go to www.militaryonesource.mil.

Thayer.rose@stripes.com

Twitter: @Rose_Lori