A bill in New Jersey is expected to be signed into law as soon as next week that would give veterans kicked out of the military solely due to sexual orientation access to state benefits. (iStock)

WASHINGTON — While gay service members can now serve openly in the military, veterans kicked out for only their sexual orientation under past policies still face hurdles to access benefits due to “less than honorable” discharges.

Some states are pushing to enact laws this year to provide immediate recourse for these veterans, rather than waiting for federal laws to change.

A bill in New Jersey is expected to be signed into law as soon as next week. It would give veterans kicked out of the military solely due to sexual orientation access to state benefits. It would also direct the state-run Department of Military and Veterans Affairs to streamline the upgrade process at the federal level.

“Under the Trump administration, nothing’s happened … in fact, we went backwards in the last four years on many equal rights issues,” New Jersey State Sen. Vin Gopal said in an interview mid-March. That’s why he, along with lawmakers in Colorado and Connecticut, are pushing for changes.

More than 100,000 service members were expelled from the military between World War II and the 2011 repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the policy that barred gays and lesbians from serving openly in the military, because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation, according to a 2020 report from Harvard Law School.

A “less than honorable” discharge -- an informal term for all discharges that are not honorable -- can bar gay service members from state and federal benefits.

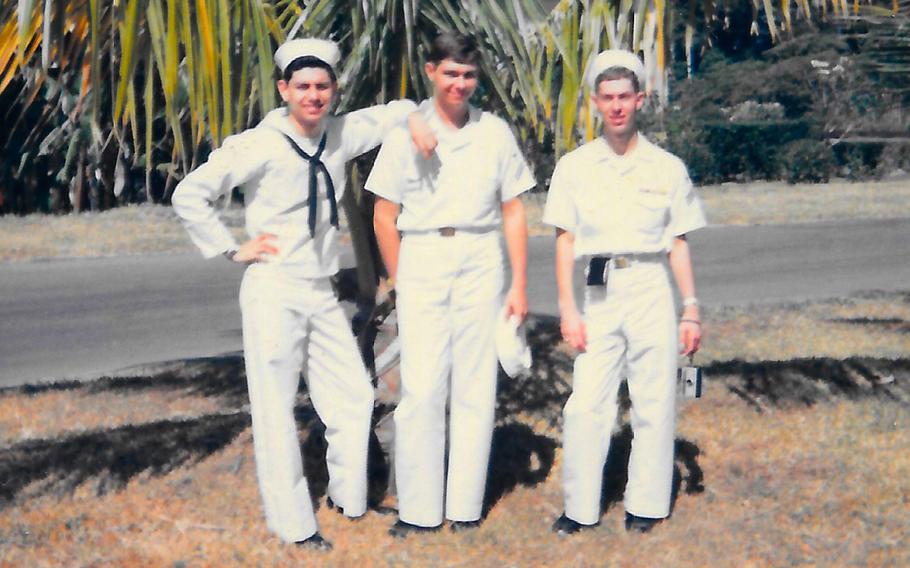

Dave Lara, left, with fellow sailors in Subic Bay, Philippines, in 1966. (Provided by Dave Lara)

Complicated forms, processing delays and bureaucratic red tape make it challenging for veterans to get an upgrade to their discharge status under the Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs. Upgrading a discharge status can take years.

New York, Rhode Island and Nevada have all enacted legislation in recent years that restored state military benefits.

Hanna Tripp, policy adviser for Minority Veterans of America, applauded state efforts.

“Removing the barriers for these people to get benefits that they might need, especially emergency benefits like housing, like [Supportive Services for Veteran Families] funding, or access to health care, that’s huge,” she said.

Lifelong effects

Service members separated without an honorable discharge can face difficulty getting a job, going back to school or obtaining a home loan.

Under a “general with honorable” discharge, one of the most common administrative discharges, a veteran is eligible for all benefits, except for the GI Bill. A notch below that is an “other than honorable” discharge, the most harsh administrative discharge, which disqualifies you from all benefits.

“An other than honorable is terrible. That means you can’t get regular VA benefits and other benefits - housing benefits, unemployment benefits are all pegged to having at least a general,” Rochelle Bobroff, director of the pro bono program at Lawyers Serving Warriors, a project of the National Veterans Legal Services Program that gives veterans free legal help with different disability claims.

Mike Mudd, an Air Force veteran, was given an “other than honorable” discharge in June 1989 after his roommate outed him as gay.

Mudd, 53, had served for less than two years when he was told to pack up and leave Homestead Air Base near Miami. He was handed $91 for a bus ticket home to Louisville, Ky.

The thriving gay community in Miami, where he had been sent after basic training, helped him realize that he was gay, and he came out during his time there. But that came at a high price.

“Because of that one thing that you can’t control, now you aren’t qualified. It just destroys you,” said Mudd, now a realtor in Kentucky, after working for 25 years as a paramedic.

His discharge prevented him from tapping into any VA benefits. Mudd was also denied a VA home loan since he was under the two-year service mark to be eligible.

In 2004, he petitioned for a hearing to upgrade his discharge. After about a year, he got it changed on a new document, but the discharge characterization, or reason why he was discharged, remained “homosexual conduct” on his original DD-214 form.

“It was a relief to get my honorable discharge, but it still hangs on me because the reason why is still on my discharge,” he said.

Now that it’s legal to serve openly in the military, he can request to strip the “homosexual conduct” label from his DD-214, something he didn’t know was possible until his interview with Stars and Stripes.

It took decades after leaving the military for Navy veteran Dave Lara to find out he could upgrade his DD-214, thanks to a veterans’ advocacy group.

Lara received a general under honorable conditions after a service member outed him in 1969. The discharge form characterized him as “unfit for any kind of military service duty, ever,” Lara, now 73, said. “And that hurt, because I was in combat, because I had to save many lives.”

After being homeless and battling symptoms of PTSD, including suicidal thoughts, he struggled to find employment. Lara eventually found success in the telecommunications industry and retired in 2003, but his discharge status continued to take a toll on his mental health.

“The self esteem that I struggled with was 80 percent because I always had that discharge. And that haunted me my whole life until I got it fixed five years ago,” said Lara, who lives in Los Angeles.

With the help of a local veterans’ service organization and a pro bono lawyer, his DD-214 was reissued and he received an honorable discharge. The process took about four years.

When he received the upgrade in 2019, he said he cried alone in his room for five hours from relief. He had that harsh discharge “always on me, always telling me that I was no value.’’

Lara urged other veterans to find support through the complex process. “You cannot do it alone,” he said.

Jennifer Dane, executive director of the Modern Military Association of America, said her organization has seen more veterans reach out for help with discharge upgrades, especially amid the coronavirus pandemic.

When COVID-19 hit, “I had so many veterans come to me to say, ‘I want to use my VA health care because I’ve lost my health care,’ ” she said.

Yet, upgrading a discharge can take from six months to three or four years. The pandemic has caused even longer delays, veterans’ advocates say.

On the other hand, Bobroff said some veterans are reluctant to jump into the process and engage with lawyers. They also might not want to focus on a traumatic experience in their life.

“You have to engage with the military, and these veterans may not want to do so because it was such a painful and unpleasant period of their life the way they were treated,” she said.

‘Rectify injustice’

Rep. Mark Takano, chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, introduced legislation early this month that would establish a commission to investigate the historic and ongoing effects of discriminatory military policies on LGBTQ service members and veterans.

Takano, the first openly gay person of Asian descent in Congress, said in a statement to Stars and Stripes in mid-March that the commission would provide a road map for Congress to “rectify injustices.”

“The full extent of the harm caused by anti-LGBTQ military policies is still not known,” Takano said.

“No veteran should face barriers to care or benefits they’ve earned — that’s why we must look back to document how veterans were denied benefits, remediate that disparity and ensure we equitably disburse future benefits to all who have served,” he said.

Takano also urged the Senate to make this issue a priority: “The longer we wait to rectify this injustice, the longer LGBTQ veterans will have to wait for their earned benefits.”

Air Force veteran Mudd and some advocates argue that current legislation does not go far enough.

Mudd wants the government to automatically change the status of all gay veterans discharged due to sexual orientation to honorable, and to remove the petition process. Better outreach and resources would also help.

“Just go back and do the right thing and treat people fair,” he said.

Cammarata.Sarah@stripes.com Twitter: @sarahjcamm