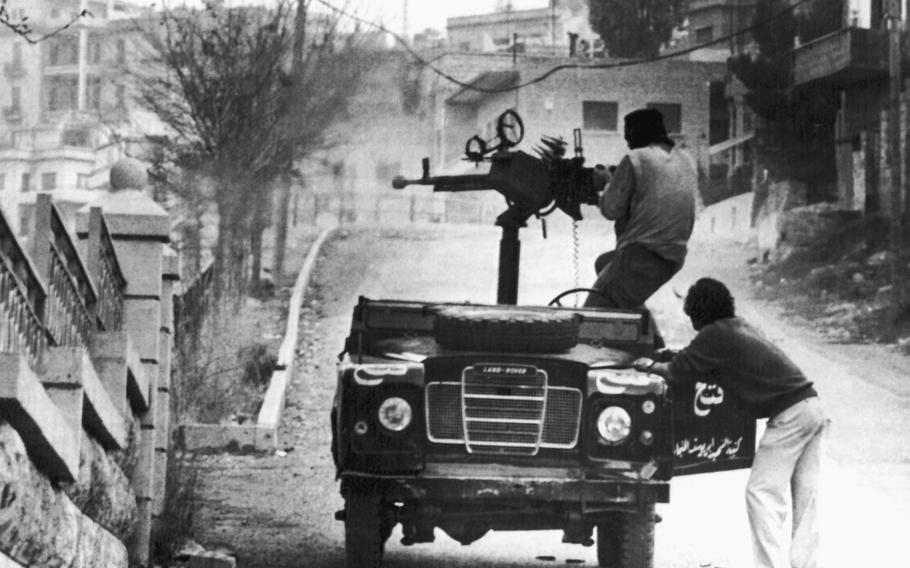

A Palestinian Fatah guerrilla fires a machine gun at Syrian troops, near the resort town of Bhamdoun, mount Lebanon. (Zuhair Saade/AP)

BEIRUT — It was an ordinary day in Beirut. In one part of Lebanon’s capital, a church was inaugurated, with the leader of the Christian Phalange party there. In another, Palestinian factions held a military parade. Phalangists and Palestinians had clashed, again, that morning.

What happened next on April 13, 1975, would change the course of Lebanon, plunging it into 15 years of civil war. It would kill about 150,000 people, leave 17,000 missing and lead to foreign intervention. Beirut became synonymous with snipers, kidnappings and car bombs.

Lebanon has never fully grappled with the war’s legacy, and in many ways it has never fully recovered, 50 years later. The government on Sunday will mark the anniversary with a minute of silence.

The massacre

Unrest had been brewing. Palestinian militants had begun launching attacks against Israel from Lebanese territory. Leftist groups and many Muslims in Lebanon sympathized with the Palestinian cause. Christians and some other groups saw the Palestinian militants as a threat.

At the time, Mohammad Othman was 16, a Palestinian refugee in the Tel al-Zaatar camp east of Beirut.

Three buses had left camp that morning, carrying students like him as well as militants from a coalition of hardline factions that had broken away from the Palestinian Liberation Organization. They passed through the Ein Rummaneh neighborhood without incident and joined the military parade.

The buses were supposed to return together, but some participants were tired after marching and wanted to go back early. They hired a small bus from the street, Othman said. Thirty-three people packed in.

They were unaware that earlier that day, small clashes had broken out between Palestinians and Phalange Party members guarding the church in Ein Rummaneh. A bodyguard for party leader Pierre Gemayel had been killed.

Suddenly the road was blocked, and gunmen began shooting at the bus “from all sides,” Othman recalled.

Some passengers had guns they had carried in the parade, Othman said, but they were unable to draw them quickly in the crowded bus.

A camp neighbor fell dead on top of him. The man’s 9-year-old son was also killed. Othman was shot in the shoulder.

“The shooting didn’t stop for about 45 minutes until they thought everyone was dead,” he said. Othman said paramedics who eventually arrived had a confrontation with armed men who tried to stop them from evacuating him.

Twenty-two people were killed.

Conflicting narratives

Some Lebanese say the men who attacked the bus were responding to an assassination attempt against Gemayel by Palestinian militants. Others say the Phalangists had set up an ambush intended to spark a wider conflict.

Marwan Chahine, a Lebanese-French journalist who wrote a book about the events of April 13, 1975, said he believes both narratives are wrong.

Chahine said he found no evidence of an attempt to kill Gemayel, who had left the church by the time his bodyguard was shot. And he said the attack on the bus appeared to be more a matter of trigger-happy young men than a “planned operation.”

There had been past confrontations, “but I think this one took this proportion because it arrived after many others and at a point when the authority of the state was very weak,” Chahine said.

The Lebanese army had largely ceded control to militias, and it did not respond to the events in Ein Rummaneh that day. The armed Palestinian factions had been increasingly prominent after the PLO was driven out of Jordan in 1970, and Lebanese Christians had also increasingly armed themselves.

“The Kataeb would say that the Palestinians were a state within a state,” Chahine said, using the Phalange Party’s Arabic name. “But the reality was, you had two states in a state. Nobody was following any rules.”

Selim Sayegh, a member of parliament with the Kataeb Party who was 14 and living in Ein Rummaneh when the fighting started, said he believes war had been inevitable since the Lebanese army backed down from an attempt to take control of Palestinian camps two years earlier.

Sayegh said men at the checkpoint that day saw a bus full of Palestinians “and thought that is the second wave of the operation” that started with the killing of Gemayel’s bodyguard.

The war unfolded quickly from there. Alliances shifted. New factions formed. Israel and Syria occupied parts of the country. The United States intervened, and the U.S. embassy and Marine barracks were targeted by bombings. Beirut was divided between Christian and Muslim sectors.

In response to the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon, a Shiite militant group was formed in the early 1980s with Iranian backing: Hezbollah. It would grow to be arguably the most powerful armed non-state group in the region.

Hezbollah was the only militant group allowed to keep its weapons after Lebanon’s civil war, given special status as a “resistance force” because Israel was still in southern Lebanon. After the group was badly weakened last year in a war with Israel that ended with a ceasefire, there has been increasing pressure for it to disarm.

The survivors

Othman said he became a fighter because “there were no longer schools or anything else to do.” Later he would disarm and became a pharmacist.

He remembers being bewildered when a peace accord in 1989 ushered in the end of civil war: “All this war and bombing, and in the end they make some deals and it’s all over.”

Of the 10 others who survived the bus attack, he said, three were killed a year later when Christian militias attacked the Tel al-Zaatar camp. Another was killed in a 1981 bombing at the Iraqi embassy. A couple died of natural causes, one lives in Germany, and he has lost track of the others.

The bus has also survived, as a reminder.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the attack, it was towed from storage on a farm to the private Nabu Museum in Heri, north of Beirut. Visitors took photos with it and peered into bullet holes in its rusted sides.

Ghida Margie Fakih, a museum spokesperson, said the bus will remain on display indefinitely as a “wake-up call” to remind Lebanese not to go down the path of conflict again.

The bus “changed the whole history in Lebanon and took us somewhere that nobody wanted to go,” she said.