The three U.S. Army Reserve soldiers killed by a drone strike in Jordan: from left, Staff Sgt. William Jerome Rivers, Sgt. Kennedy Ladon Sanders and Sgt. Breonna Alexsondria Moffett. (U.S. Army)

A drone attack that killed three U.S. soldiers in Jordan last year was most likely preventable, according to a military investigation that determined numerous failures — from complacency and indecisiveness to outright negligence — contributed to the worst assault on American troops since the fall of Afghanistan.

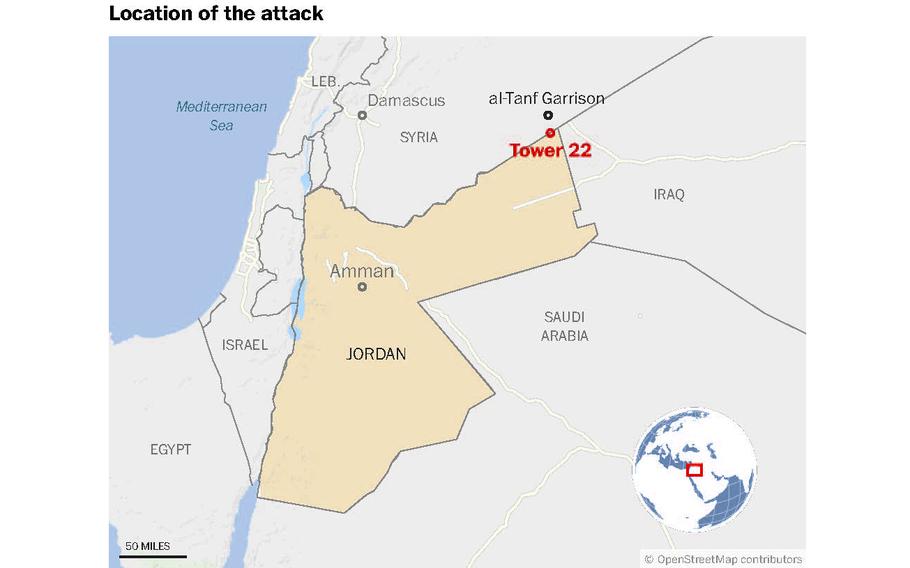

The small outpost, known as Tower 22, is along Jordan’s border with Syria and Iraq, and largely had been spared from the assaults on American positions in those countries by Iranian proxies furious with the United States for its support of Israel’s war in the Gaza Strip. However, on the morning of Jan. 28, 2024, while most of the base’s 350 troops slept, there were indications an attack might be imminent, Army investigators learned.

An intelligence report transmitted to Tower 22 approximately 90 minutes before the strike warned that militia groups had discussed openly on social media their intent to target U.S. forces in the area, prompting Tower 22’s second-in-command to tell the watch team to “stay vigilant.” But when their radar picked up an unknown object heading toward the base, no one assessed it as a threat — and, vitally, no one issued an order for everyone to take cover, the investigation found.

Four minutes later, a powerful explosion throttled the base’s living quarters.

Oneida Oliver-Sanders, whose 24-year-old daughter, Sgt. Kennedy Sanders, was killed in the attack, told The Washington Post that when Army officials explained the investigation to her family, they were thorough and forthright about the lapses that were found. She said she was encouraged to learn there were other troops who braved danger to help but disturbed that the attack drone was allowed to breach the base’s defenses.

“They did have time to alert them to take cover, and because of poor judgment, they didn’t,” Oliver-Sanders said.

Also killed in the blast were Staff Sgt. William Jerome Rivers, 46, and Sgt. Breonna Alexsondria Moffett, 23. More than 70 personnel were wounded, some seriously.

This account is based on the voluminous report detailing the Tower 22 investigation, a copy of which was obtained by The Post via the Freedom of Information Act, interviews with the slain soldiers’ survivors, and a separate summary of the findings the military provided to them. The report is more than 4,500 pages, though the Army withheld more than half of it and redacted much of the material it released.

The incident is the only deadly strike on U.S. troops since Iranian-backed militants unleashed their campaign of violence in response to the Gaza war. The Pentagon rushed additional defenses to the region to shore up protections for deployed service members, but Tower 22, a support base for another American outpost nearby in Syria, was deemed to be at lower risk of attack, officials have said.

The investigation’s findings appear to have some contradictions. For instance, investigators faulted Tower 22’s leaders for failing to “visualize risk” and not appreciating the likelihood of an attack.

Yet commanders above them also failed to envision the base’s vulnerability. Four months before the attack, Army Central, which oversees operations throughout the Middle East, denied a request for an air defense system capable of shooting down drones because, investigators found, only one such system was available and troops in the United States needed it to prepare for deployments. A request for a radar system that could better detect drones also was denied, the report said.

The only counter-drone defenses at Tower 22 were electronic warfare systems designed to disable the aircraft or disrupt their path to a target, according to the investigation and previous reporting by The Post.

A spokesperson for Army Central did not respond to repeated requests for additional information, including who at Army Central denied Tower 22’s appeal for an air defense system.

The Sanders family was told that four officers faced disciplinary action as a result of the attack. The investigation does not identify them or detail what their punishment was.

(The Washington Post)

The attack

While senior military leaders determined there was less risk facing Tower 22, soldiers posted there would later report increasing unease. In October, a drone was brought down outside the base perimeter, and smaller reconnaissance drones were seen nearby in subsequent weeks but troops struggled to detect or disable them.

Sanders, Rivers and Moffett belonged to an engineering unit responsible for reinforcing Tower 22’s defenses. Rivers, an experienced noncommissioned officer, helped oversee electrical work. Moffett and Sanders operated heavy machinery such as bulldozers and excavators.

The day before the attack was spent preparing for construction projects. After dinner, Sanders and Moffett went to a tent to partake in one of the few luxuries of a Middle East deployment: playing a few rounds of “Call of Duty.”

After 1 a.m., they retired to the spartan housing unit they shared. While they slept, the night crew in the Base Defense Operations Center, or BDOC, monitored intelligence streams and the facility’s air defense systems. At one point, a laser was pointed at Tower 22 from Rukban, a camp less than two miles away housing thousands of displaced Syrians.

Just past 4 a.m., Tower 22 received the report that a Telegram channel affiliated with local militias had posted about plans for a drone attack, the investigation says.

At 5:30 a.m., troops in the operations center watched as a U.S. drone finished a surveillance flight. A minute later, the screen pinged, showing an unknown object approaching Tower 22 from the south, but the watch team — and a powerful surveillance camera — was focused on the friendly drone as it came in to land, the report says.

At 5:35 a.m., the investigation says, a low whirring sound, like a lawn mower, could be heard — and then a fiery blast.

A leader, who is not identified in the report, burst into the BDOC and screamed, “How did you guys not see it?” the report says. The call was sounded for everyone to take cover, and people raced barefoot to the bunkers as shrapnel and other debris rained down.

Once the all-clear was given, personnel rushed to the wreckage to look for survivors, pushing through their own injuries and with the threat that more attack drones could be on the way.

Rivers was killed on impact and buried in rubble, the report says. The force of the explosion propelled Sanders onto the roof her housing unit. She and Moffett were unresponsive and taken to the surgical station, which was overwhelmed with patients. Physicians tried to resuscitate Moffett, but the crush of wounded personnel forced them to move on to troops they felt they could save, the report says.

A “vampire” call was announced over the loudspeaker, and service members lined up to donate blood. It was an urgent and dangerous moment. Some time later, another drone approached and was shot down by an air defense system at the Tanf Garrison, a U.S. base 13 miles away in Syria, the report says.

The base chaplain administered final rites to Sanders, Moffett and Rivers, and fellow service members guarded their remains before a helicopter arrived to evacuate them.

Problems exposed

The Army’s investigation places significant blame on the operations center’s leadership and crews. The attack was allowed to happen because of their “failure to interrogate or assess the unidentified aircraft” that pinged on the radar, the investigation concluded.

Troops monitoring for incoming threats told investigators that they did not see the drone on their screens, describing instead two objects they assessed were birds or too far away to be a concern.

Yet when there was an opportunity to alert base personnel to a possible threat, there was confusion among troops in the operations center about roles and responsibilities, the investigation found. The night shift was considered the most likely period an attack could occur, but an enlisted leader, rather than an officer, was in charge and as a result the crew “did not feel fully empowered to make important decisions,” the report says, “even when faced with imminent danger to the base.”

Leaders at Tower 22 also failed to implement proper training, and the base’s battle drills were “inadequate,” investigators determined.

Service members told investigators that watching the friendly drone land may have distracted them from scrutinizing the unknown object. The militants also may have anticipated the landing was a moment the base had limited views of inbound threats and programmed their attack drone to strike about the same time.

Other factors included “cumulative exhaustion” among the night crew and radars that don’t classify whether incoming objects are drones. In response, Army officials reduced the night shift from 12 to eight hours, assigned more leadership to the base and conducted more training.

Francine Moffett told The Post that she was comforted to learn her daughter received final rites, but overcome by the thought she could not hold her in her last moments. She said she struggles to recall much from the Army’s briefing.

“When you say her name, and say deceased, you can’t hear anything else,” Moffett said.

Her daughter’s legacy has endured, though. Breonna Moffett was a reservist and, when not fulfilling her Army duties, worked at a treatment center for cerebral palsy, which created an award in her honor.

Shawn Sanders, Kennedy Sanders’ father, said he and his wife were heartened by the dedication of her fellow troops who ensured their daughter’s remains were protected, though he acknowledged it was difficult to accept the failures investigators found.

“It’s beyond frustrating to know four minutes elapsed and human error allowed this to take place,” he said.

His daughter was full of potential and planned to study radiology, he explained, and after her death, their community in Waycross, Georgia, came together to support the family.

Today, a section of their street has a new name: Kennedy L. Sanders Way.

Aaron Schaffer contributed to this report.