Georgia Army National Guard soldiers exit a CH-47 Chinook helicopter for a training mission in support of Operation Inherent Resolve near al-Tanf Garrison in Syria on Oct. 29, 2024. (Mahsima Alkamooneh/U.S. Army)

U.S. troops fighting Iranian-backed militias and a resurgence of the Islamic State in eastern Syria face an uncertain path forward as insurgents entering Damascus remake the balance of power in the Middle East.

On Sunday, fighters led by the group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham had reached the capital, effectively ending Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s rule.

It’s a stunning reversal of fortunes in a 13-year civil war that also leaves Assad’s long-time ally Iran with diminished influence in the region.

The rebel advance, which accelerated a little over a week ago with the surprise takeover of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, is taking place hundreds of miles from a key U.S. outpost in the country’s east.

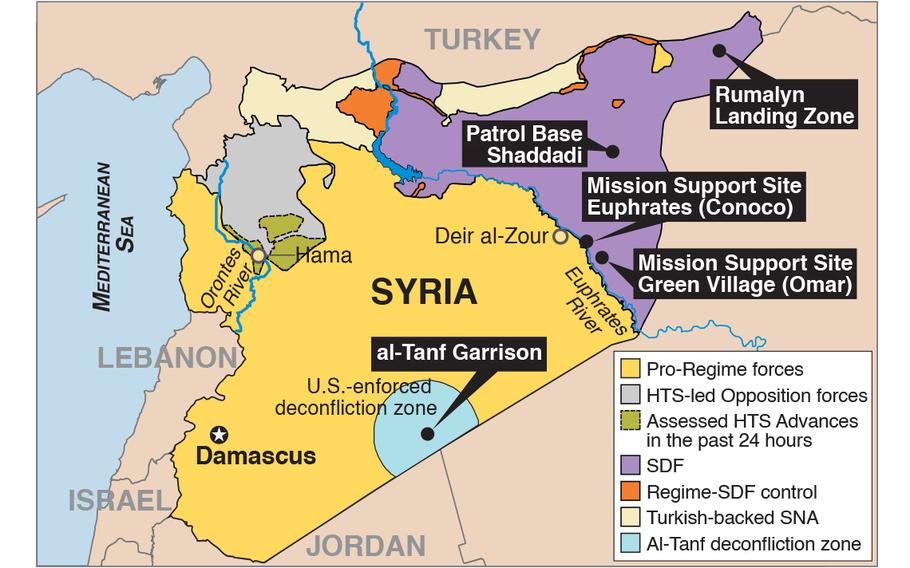

Mission Support Site Euphrates, also known as the Conoco gas field site, is among at least four U.S. bases strategically scattered across northeastern Syria, a territory controlled primarily by Kurdish allies in the fight against the Islamic State.

The base, a de facto territorial dividing point between Tehran’s proxies and the U.S.-led coalition, is a frequent target of rocket and drone attacks.

Some of those attacks appear to be facilitated by the Syrian regime, analysts told Stars and Stripes last month.

With adversaries emboldened by the pending withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq, the base has become a front line for pressuring American troops to leave Syria, they said.

About 900 U.S. troops and an unspecified number of contractors are assigned to MSS Euphrates and other bases, including Mission Support Site Green Village, sometimes referred to as Omar, about 29 miles south of Conoco.

Patrol Base Shaddadi and Rumalyn Landing Zone are farther northeast, closer to Syria’s border with Iraq. A fifth U.S. base, al-Tanf Garrison, is situated southeast near the country’s borders with Iraq and Jordan on a highway leading to Damascus.

It’s not clear exactly how many other sites the U.S. maintains in Syria, but smaller operations appear to be near the city of Qamishli at the Turkish border and by the town of Malikiyah, both in the northeast, according to a Washington Institute for Near East Policy online tracker.

Zones of control in Syria as of Dec. 5, 2024. In the west, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham has made rapid advances into areas once controlled by the Assad regime. Several areas are contested between the regime and U.S. backed Syrian Democratic Forces. (Noga Ami-rav/Stars and Stripes)

While American military personnel are primarily focused on preventing an ISIS resurgence, the U.S. presence also occupies “a space that otherwise, the Iranians and Russians would fill in eastern Syria,” said Michael Knights, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute and expert on military and security affairs in Iran, Iraq and the Gulf states.

If the U.S. were to leave, uncontested control of the region would give Iran a much-needed land bridge to Hezbollah in Lebanon, said Knights, who along with other analysts spoke with Stars and Stripes in the days prior to the rebel occupation of Damascus.

“The Israelis also have a strong interest in preventing that from happening, so … there’s two missions, basically, for the U.S. forces there,” Knights said.

At the same time, Iran’s ability to influence events in the region will suffer markedly if the insurgents hold their territorial gains and complete their takeover of the government.

Iran likely would no longer be able to use Syrian territory as a conduit to reach Hezbollah fighters in Lebanon, who already had their attack capabilities diminished by fighting with Israel.

Meanwhile, U.S. troops in recent weeks have shown signs of stepping up their responses to increasingly frequent strikes by Iranian-backed militants.

On Tuesday, U.S. forces destroyed three truck-mounted rocket launchers, a T-64 tank and mortars following an attack on MSS Euphrates, Pentagon spokesman Maj. Gen. Pat Ryder said the same day.

The strike occurred after several rockets landed near the base and U.S. troops came under mortar attack. The Pentagon announced Thursday that three service members were being evaluated for potential traumatic brain injuries resulting from the attack.

It remained unclear which group was behind the offensive against U.S. military personnel, but Ryder acknowledged during a briefing Thursday that Syrian regime troops also operate in the area.

Tuesday was the second time in a week the U.S. preemptively targeted a threat to MSS Euphrates. On Nov. 29, A-10 fighter jets successfully attacked militants preparing a rocket rail, according to the Pentagon.

Those strikes are solely to protect military personnel and are not connected to the ongoing civil war, American officials have emphasized.

“Our forces are in Syria to conduct a counter ISIS operation ... the enduring defeat of ISIS,” Ryder said. “Our forces in that region were threatened. We took action to mitigate that threat and will do so again.”

U.S. soldiers conduct an indirect fire exercise in Syria on Sept. 21, 2024. (Solimar Rivera/U.S. Army)

The U.S. resolve to keep its mission narrowly defined could be tested if Turkey sees an opportunity to cripple Kurdish fighters battling ISIS, analysts say.

The U.S. alliance with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces has long been a flashpoint in America’s relations with Turkey, a fellow NATO member.

Turkey considers the group, which controls a large swath of northeastern Syria along the Turkish border, an offshoot of a larger Kurdish network deemed a terrorist organization.

Inspired by their success in Aleppo, some Turkey-backed Arab insurgents seized the momentum to take control of a Kurdish-held city and nearby villages.

That gain could entice Turkey to deal more decisively with the Kurds, which would pose a dilemma for the U.S., said Steven Heydemann, a senior resident with the Washington D.C.-based Brookings Institute’s Center for Middle East Policy.

“It would really confront the U.S. with the question of how far it’s willing to go to defend its long-standing partner in northeastern Syria,” Heydemann said.

However, the U.S. typically has stayed out of clashes between the SDF and other groups such as the Syrian National Army, which is backed by Turkey, he added.

The U.S. also could see increasing attacks on its troops in Syria if any of the combatants conclude that America is against them, Knights said.

“There’s just a dizzying number of armed forces (in Syria) who are clashing with each other, and the fighting is very kind of mobile and fluid,” he said. “So, there’s a lot of room for misunderstanding and attributing actions to the U.S. that actually (have) nothing to do with the U.S.”

Conversely, Iranian-backed militia forces’ strikes against the U.S. also could decrease if those groups are redirected elsewhere.

In that scenario, it’s unlikely that remnants of Assad’s forces that analysts say have been assisting them would attack U.S. troops directly.

“Such actions could provoke a robust U.S. response,” said Armenak Tokmajyan, a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut.

U.S.-led coalition forces train near al-Tanf Garrison in Syria on Oct. 29, 2024. American forces in northeastern Syria are working to prevent a resurgence by the Islamic State. (Mahsima Alkamooneh/U.S. Army)