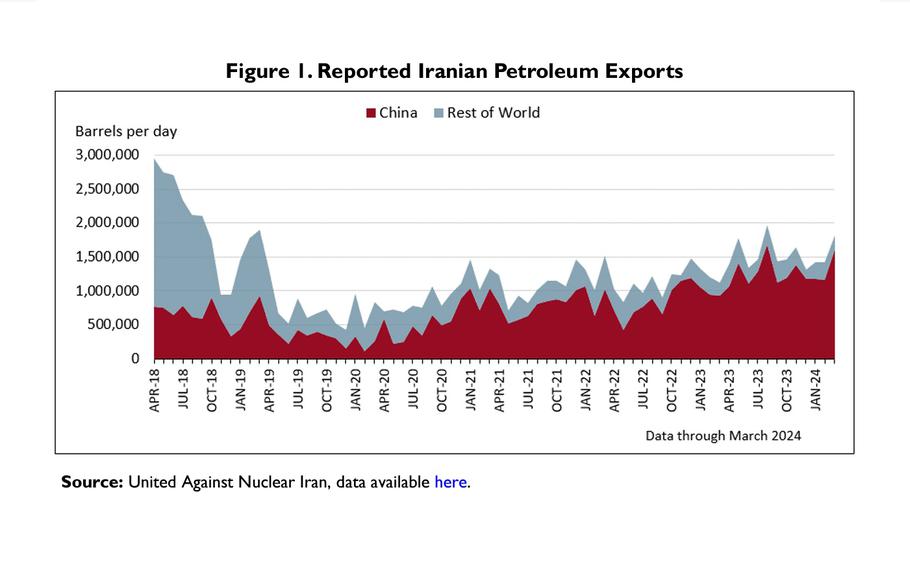

A chart of Iran’s petroleum exports from early 2018 to early 2024, produced by the Congressional Research Service in a report titled “Iran’s Petroleum Exports to China and U.S. Sanctions.” (Congressional Research Service)

China and Iran flaunted their close friendship this week.

At a meeting in Russia aimed at solidifying an anti-Western alliance, Chinese leader Xi Jinping welcomed Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian to Iran’s first BRICS summit as a full member. He also made a show of Beijing’s diplomatic and economic alliance with Tehran as conflict in the Middle East further escalates, and Iran braces for Israel to retaliate against it for recent attacks.

“China will unswervingly develop friendly cooperation with Iran,” Xi told Pezeshkian, according to a Chinese government readout. Xi expressed his support for a cease-fire in the Gaza Strip, and the two leaders agreed to work together on “opposing hegemony and bullying.”

But with violence threatening to bring the long-standing shadow war between Israel and Iran into the open, China is unlikely to force Iran to de-escalate, and the relationship between Beijing and Tehran is more restricted than it appears.

“China’s relationship with Iran is strategically important, but also limited,” says William Figueroa, a China-Iran expert at University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “It’s certainly not this new axis of evil that people portray China, Russia, and Iran to be. It’s actually one of its lesser, more minor relationships in the Middle East, and I think that gets lost.”

Economically isolated due to a strict international sanctions regime, Iran is dependent on commercial ties with China, its largest trading partner. That, together with their shared distrust of the United States, has contributed to stronger political ties.

Iran last year joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a political and economic organization established by China and Russia, with Beijing’s encouragement, and was this week welcomed into BRICS with the help of Beijing. In February 2023, amid both countries’ rising tensions with Washington, Pezeshkian’s predecessor led a large delegation to Beijing in a high-profile state visit. It was the first by an Iranian president in 20 years.

China has taken advantage of the opportunity to buy oil cheaply from heavily sanctioned Iran, with oil exports from Iran to China increasing more than 25 percent in the first nine months of 2024 compared to the same period last year. Sales hit an all-time high this August, of 1.66 million barrels per day, according to data from Vortexa, an energy analytics firm.

But the two countries’ overall bilateral trade has diminished in the past decade and is dwarfed by China’s trade with Iran’s Gulf neighbors. Last year, for example, China’s trade with Iran was only one-seventh of that with Saudi Arabia, according to Chinese trade data.

If Iran and Israel end up in direct conflict, China’s oil supply from Iran could be disrupted. But analysts agree that this wouldn’t have a disastrous impact on Beijing, as China could lean on its strategic oil reserves and other suppliers, like Russia and Venezuela.

“They have a pretty strong hand in terms of being able to sit this out,” said Alex Turnbull, a Singapore-based commodities analyst.

Still, China has used its economic relationships with Iran and other Gulf nations to establish itself as something of a power broker in the region.

Beijing last year announced a détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, surprising Washington, which had been the dominant outside dealmaker since the end of the Cold War. It underscored Xi’s ambitions to stake out a larger political presence in the Middle East.

Then earlier this year, Beijing, which has increasingly aligned itself with Palestinian leaders since the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks on Israel, announced a deal between Palestinian factions, including Hamas and Fatah, to increase unity among bitter rivals during the war in Gaza.

But that Palestinian agreement has not amounted to anything, and even China’s landmark Saudi-Iran deal reveals the limitations of its influence.

“China didn’t do much, basically,” said Ahmed Aboudouh, an expert on Middle East-China relations at Chatham House policy institute in London. “The Iraqis and Omanis played a very important role for two years to bring these sides together, and China just came and put its great power stamp on the agreement and got the photo op.”

China’s leverage over Iran remains minimal, analysts say, even as Chinese diplomats have been dispatched to confer with their Iranian counterparts. Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, meanwhile told his Israeli counterpart last week that Beijing wants to “play a constructive role in cooling down the situation and restoring peace in the region.”

Jonathan Fulton, an Abu Dhabi-based expert on Chinese policy toward the Middle East at the Atlantic Council, said China had been “rhetorically very active” but hadn’t come up with a tangible result.

China’s approach was more bark than bite, Fulton said. “As in so many other things, the further you get away from its borders, the more bark.”

But Beijing, which vaunts the principle of “noninterference” in other nations’ affairs, is neither willing nor able to exert influence over Tehran in the current precarious moment, Figueroa said.

“What they have done is what they can do,” he said. “They have proposed to all of their allies and to the United Nations multiple times to have some sort of peace summit for diplomatic negotiation. They’ve called over and over again for a cease-fire. The fact is just that it’s not within their power to make any of those things happen.”

Xi this week doubled down on his rhetoric calling for peace in the Middle East.

“As the world enters a new period defined by turbulence and transformation, we are confronted with pivotal choices that will shape our future,” he told the BRICS summit on Wednesday. “Should we allow the world to descend into the abyss of disorder and chaos, or should we strive to steer it back on the path of peace and development?”

But for Xi, being seen as striving toward this goal, particularly in the developing world, may be more important than successfully brokering peace.

Chinese leaders are not “judging success or failure based on whether they successfully mediated an end to the conflict,” said Oriana Skylar Mastro, an expert on the Chinese military at Stanford University and author of “Upstart: How China Became a Great Power.”

“The Chinese are seeing it mainly as a lever and tool of global influence. And so what really matters to them is … does it improve their image if it looks like they’re playing a mediating role?” she said.

Pei-Lin Wu in Taipei, Taiwan, contributed to this report.