Palestinians in the rubble of destroyed buildings hit by Israeli missiles in the center of Khan Younis, southern Gaza, on Monday, Oct. 30, 2023. (Ahmad Salem/Bloomberg)

Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip has reduced entire neighborhoods to dust. The resumption of fighting and intensified airstrikes on southern Gaza after a week-long pause could mean that even more of the territory could meet the same fate.

But the war, however long it continues, is only the beginning. Parts of a postwar Gaza could long be dangerous to inhabit, let alone rebuild.

Riddled with hundreds if not thousands of unexploded ordnance, ranging from makeshift rockets built by Hamas to high-tech munitions provided to Israel by the United States, “the contamination will be unbelievable, like something from World War II,” said Charles Birch, an explosives clearance expert for the U.N. Mine Action Service (UNMAS) who was in Gaza at the height of the bombing campaign.

Birch estimated it would cost tens of millions of dollars and take many years to make the entire area safe.

An estimated 80 percent of Gazans have been displaced by the war, alongside the three percent of people who lived in the strip who have been killed or injured. The majority of casualties were women and children, according to the Gaza Health Ministry.

Reversing that displacement would be a mammoth task. Buildings have been leveled or made structurally unsound. Infrastructure, including for water and sewage, has been destroyed. Many weapons that analysts say have been used in Gaza, including the controversial incendiary white phosphorus, can seep into the water supply.

Israel says it aims to destroy Hamas, and the question of who will have the authority or resources to rebuild the economically devastated enclave remains unanswered.

Unexploded ordnance might be the most pervasive threat. Even during times of relative peace in Gaza, leftover bombs from previous rounds of fighting regularly kill and maim. The problem is now exponentially worse, and the danger will grow as explosives degrade and get more unstable.

Unexploded ordnance is a long-lasting legacy of war, posing risks to civilians for generations.

Some, such has the land mines strewn across Ukraine after Russia’s invasion, are meant to lie dormant. But others are the result of failures to detonate. Bombs from World War II are still found underground in Europe, prompting evacuations.

Small explosive weapons often look like toys to children. A large bomb buried deep underground can be inadvertently triggered during reconstruction efforts, leading to deaths long after a conflict is over.

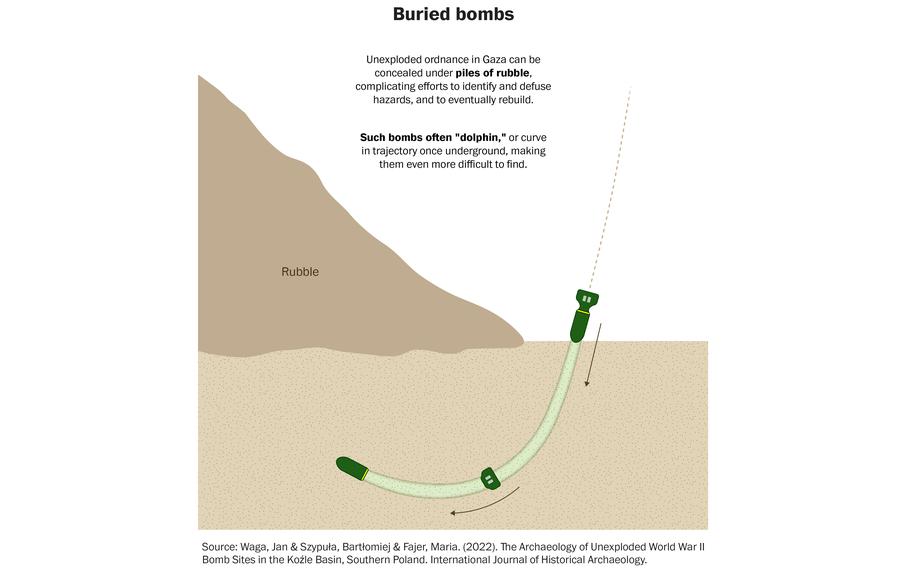

(The Washington Post)

UNMAS and other expert groups say that in general, one out of every 10 munitions fails to explode, although the figure varies significantly by type of weapon. It could be much lower in some newer munitions, and affected by factors including length and conditions of storage, weather and target.

“You’re going to have higher rates of failure in an urban setting because a lot of ammunition types will have a soft landing through a roof first, then multiple stories,” said James Cowan, who leads the HALO Trust, a nonprofit that clears land mines.

The situation in Gaza is somewhat akin to that of the Iraqi city of Mosul, following the battle to liberate it from the Islamic State in 2017. In 2021, UNMAS said it had cleared more than 1,200 ordnances from Tal Kaif, an area north of Mosul, alone.

But Gaza may represent a more complex problem. Simon Elmont, a demining expert for the nonprofit Humanity & Inclusion who worked in Mosul and other cities retaken from the Islamic State, said there was often a relatively untouched area where civilians could live while ordnance experts worked elsewhere.

Gaza City, on the other hand, will be “largely uninhabitable whilst the clearance operations are ongoing,” Elmont said.

The city’s crumbling high-rises, tight alleyways and underground tunnels potentially concealing Hamas rocket factories would take a painstaking process to clear. Some piles of rubble appear to tower 100 feet. Controlled surface detonations to clear ordnance risk setting off buried explosives.

“You have to look at it three-dimensionally,” including what’s below the rubble, said Gary Toombs, a former mine disposal expert with the British Army who works with Humanity & Inclusion.

Many of the weapons thought to have been used in Gaza are designed to not explode on contact, but have a delayed fuse that allows them to go off underground or within buildings. These munitions can be difficult to locate if they fail.

Rockets used by Hamas and other militant groups, some intended for Israel that land in Gaza, are believed to have a high failure rate.

Israel has not released precise figures on the munitions it has used. At the start of November, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant said that Israel had dropped 10,000 bombs on Gaza City, a number that could not be verified independently. Experts say the destruction of heavy infrastructure indicates the use of large bombs such as the 2,000-pound Mark 84, an unguided “dumb bomb,” retrofitted with the U.S.-supplied JDAM system to become a precision weapon.

Brian Castner, a weapons expert for the rights group Amnesty International who worked in ordnance disposal in the U.S. Air Force, said that scrap has been found in Gaza from the Boeing-manufactured JDAMs, which stands for Joint Direct Attack Munition. These guidance systems are often attached to 1,000- or 2,000-pound bombs such as the Mark 84, he said.

These weapons are not known to have a high failure rate, but numerous instances of failure were documented when Israel used them during its 2021 conflict with Hamas, he said.

U.S. lawmakers have criticized the Biden administration for a lack of transparency about the number of weapons it has sent to Israel — in contrast to military aid sent to Ukraine.

“We’ve got no idea what’s there,” said Birch of UNMAS.

Israel is not documented to have used cluster munitions, which pose heightened concerns about indiscriminate impact and high failure rates, in the ongoing conflict, though it has in the past. But clearance experts worry that Israel’s wide use of newer weapons could pose challenges.

While deminers have some familiarity with U.S.-made JDAMs or explosive artillery rounds, for example, most have worked less with Israeli-produced precision weapons such as the Spike missile series.

“It can be very complicated type of fuzing in these items,” said David Willey, a demining expert for the Mines Advisory Group.

Manufacturers rarely help deminers, and defusing techniques used by militaries are often classified.

Clearing Gaza will also be complicated by strict border controls. Controlled detonations require explosives. In past rounds of conflict, the lack of ground-penetrating radar meant that demining teams found themselves prodding through rubble and soil with primitive means, including bamboo sticks and digging by hand.

Ground-penetrating bombs or missiles often shift from vertical to horizontal travel, sometimes even coming back toward the surface in a phenomenon some experts call “dolphining.”

It might take up to 30 contractors digging into rubble for more than a month to find and defuse a single bomb in Gaza, at a cost of up to $40,000 per bomb for UNMAS, Birch said.

Globally, funding for demining efforts has decreased. Much of the overall attention is focused on Ukraine.

Gaza’s interior ministry has a disposal squad. Experts from this group told reporters in 2021 that it had conducted 1,200 searches for unexploded ordnance after that year’s conflict, which lasted 11 days and saw far lower rates of bombing.

The Gazan team had few resources before the war; its status after the war is at best uncertain. “I can see no circumstance in which a humanitarian organization such as my own could function in Gaza with the return of Hamas,” said Cowan of HALO.

The IDF declined to comment on the issue of unexploded ordnance or the degree to which it would help with clearance. Israel, unlike the United States, is not a party to the international agreement that seeks to limit the impact of unexploded ordnance, the 2003 Protocol on Explosive Remnants of War. The language of the agreement focuses on parties directly involved in conflicts.

“This is a treaty negotiated by states, and states are going to try to limit their obligations, particularly with respect to arms they’ve sold to someone else,” said Brian Finucane, a senior adviser at the International Crisis Group and former legal adviser at the State Department.

(The Washington Post)