Middle East

Inside ‘little Gaza’: The civilians trapped in a West Bank war zone

The Washington Post December 5, 2023

Civilians walk in the heavily damaged neighbourhood of a-Damaj in Jenin refugee camp on Nov. 29, 2023. (Lorenzo Tugnoli for The Washington Post)

JENIN REFUGEE CAMP, West Bank — The nightly exodus begins at dusk.

“Don’t forget your pajamas,” Ahlam Abu Gutna, 45, told her three children as she gathered them on the roof of the family’s two-story house last Tuesday evening for a quick embrace.

They took a last look at the refugee camp sloping down the hill before filing downstairs to pack for another night away.

Rose Bani Gharra, 16, shoved school books and a wool hat into her backpack. Her sister Razan, 13, put a purple T-shirt and a Quran into hers. Mohammed, 11, tried to leave the house with his arms full of notebooks, but Rose told him to put them back — they were too heavy. He grabbed his Rubik’s Cube instead, fiddling the colored tiles into place as his mother tied his shoes.

Ahlam’s husband, Ahmad, 46, took out the trash and performed the sunset prayer. A few minutes later, the family piled their belongings into their car and drove through winding streets toward the outskirts of town.

Similar scenes play out nightly across the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank, which has transformed over the past month into an undeclared war zone. Since Oct. 7, at least 52 Palestinians have been killed as of Sunday in the camp — nearly a quarter of the 234 killed by Israeli forces across the occupied territory during that period, according to the latest U.N. tally.

In response to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack, Israel has stepped up raids in and around the camp to kill or capture militants. Among them was Ahlam’s nephew, Thaier, who was killed in a raid on Nov. 9. His portrait hangs between two buildings in their neighborhood, where photos of dead fighters — known here as martyrs — peer out from every corner.

Residents say the incursions over the last month have been more frequent — and more violent — than any they’ve experienced in decades. Following a template established by Israel during a blistering two-day raid in July, they now involve drone strikes that can destroy multistory buildings in an instant.

Bullet holes in the window of Jenin’s public hospital on Nov. 28, 2023. (Lorenzo Tugnoli for The Washington Post)

Fear of the airstrikes appears to be driving the mass outflow from the camp at night, said Adam Bouloukos, West Bank director of affairs for UNRWA, the U.N. Palestinian refugee agency. His staff estimates as many as two-thirds of the camp’s residents have been leaving regularly to sleep elsewhere since the raids began in earnest in early November.

Some go bunk with relatives. Those who can afford it move to hotels or rented rooms. The poorest stay behind.

“Each night of leaving, you see Jenin camp resembles a horror movie — like a big house where there’s no people,” Ahlam said.

For those with the means and ability to leave, the escape offers some reassurance that they and their children will live to see another day. But it comes at a significant cost, disrupting work, school and daily routines.

“Collecting your things and taking them to another house and then at 7 a.m., returning here,” Ahlam sighed, “that’s not a life.”

Like others in the camp, Ahlam fears the temporary moves are a prelude to a more permanent displacement — a second Nakba, or “catastrophe,” the term Palestinians use for their mass dislocation in 1948.

As she prepared to go, Ahlam paced back and forth in her living room, clutching her stomach. Her nephew, Ismail, 25, said doctors had concluded her stomach pain was caused by psychological distress.

The family drove to a one-room cottage Ahmad built in an olive orchard outside of town. They arrived after dark, lighting the path with their phones.

Inside, there’s electricity, but no heater or stove. A TV mounted on the cottage wall is always turned to Al Jazeera; images of displaced Gazans picking their way through rubble form the backdrop of their nights.

At 6 p.m. last Tuesday, Ahlam hugged her son on a mattress laid out on the tile floor, where 13 members of the extended family would crowd together to sleep.

“There is no one helping us. Jenin is forgotten because there is another war,” she said. Palestinians “call Jenin ‘the little Gaza.’”

The camp, home to more than 22,000 people, was established in 1953 to house Palestinians displaced during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Along with the surrounding city of Jenin, it is nominally controlled by the Palestinian Authority, the governing body in parts of the West Bank. But in a community that has long been a bastion of armed resistance to Israeli occupation, militant groups are the true authority. At night, Israeli forces hunt them.

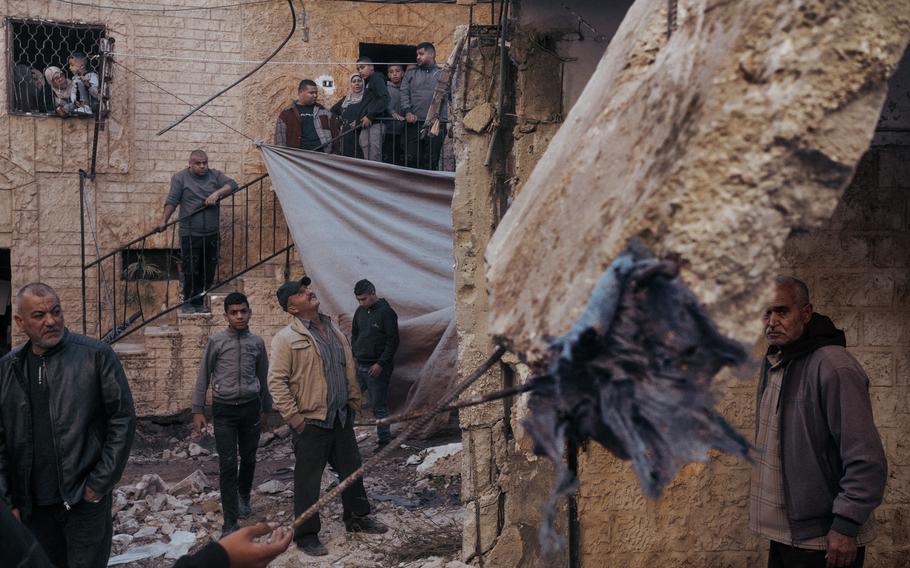

Civilians gather in the heavily damaged al-Damaj neighborhood on Nov. 30, 2023. (Lorenzo Tugnoli for The Washington Post)

The raid

Two hours later, sirens blared through Jenin. The Israelis were on their way.

First came the buzz of drones, followed by the boom of explosions from the direction of the camp and the pop-pop-pop of gunfire. An Israeli armored vehicle rolled down an abandoned street in Jenin city, in view of Washington Post reporters. A dark figure with a rifle ran into the road and began shooting at the soldiers.

Military vehicles surrounded Jenin’s public hospital, a maneuver local health officials described as part of an Israeli strategy to cut off access to lifesaving care and arrest suspects from ambulances. Medics, who now wear flak jackets, have been shot or threatened by Israeli soldiers during the incursions, according to Wisam Bakr, the hospital’s director.

“All of the hospitals are surrounded,” Mahmoud al-Sa’adi, director of the Jenin branch of the Palestine Red Crescent Society, which operates most of the city’s ambulances, told The Post by phone late Tuesday as the raid intensified. “They arrested a wounded man in an ambulance who was shot in the leg.”

Israeli checkpoints and military vehicles prevented most ambulances from helping the injured at all, he said.

Residents of Jenin — those still left in the camp, and those who evacuated to safer places close by — passed a sleepless night, listening to the explosions. They shared videos on social media of military vehicles driving through the streets, soldiers climbing over walls and Israeli forces shouting through megaphones at civilians to evacuate.

Armored bulldozers were filmed tearing up roads, rendering some impassable. Telegram channels linked to local militant groups provided updates on the latest Israeli positions throughout the night.

At dawn Wednesday, the streets of central Jenin city were empty and quiet, save for the sound of distant gunfire from the camp. A loud boom sent a flock of pigeons soaring skyward.

Israeli troops pulled out of the Jenin public hospital compound later that morning. Bleary-eyed doctors emerged blinking into the sunlight. Across the courtyard, children who had sheltered with their mothers at the hospital overnight peered out of open windows, not flinching at the sound of gunfire.

In the early afternoon, two ambulances came screaming into the driveway. From the first, paramedics pulled a boy with a bullet hole in his head. They frantically pumped his chest, but his feet and face were already turning gray.

“Allahu akbar,” an onlooker whispered, standing in the door of the hospital as the boy was wheeled by.

Next came an older boy who had been shot in the abdomen. He lay still on a stretcher, and was followed into the emergency room by a fighter toting a rifle.

The Palestinian Health Ministry announced the boys’ deaths that afternoon, identifying them as Adam al-Ghoul, 8, and Bassem Abu el-Wafa, 15.

Two CCTV videos synced and geolocated by The Post show the moment they were shot, as they stood with two other boys near an intersection in Jenin city. In his right hand, Wafa holds an object that is roughly the size of his palm. He appears to try to light the object several times as he moves toward the middle of the road. The Post was not able to confirm what he held.

Ghoul stands half a block behind Wafa. He turns to run. A second later, gunshots ring out and he falls to the ground.

Asked about the shooting, the Israel Defense Forces said in a statement: “A number of suspects hurled explosive devices toward IDF soldiers. The soldiers responded with live fire toward the suspects and hits were identified.”

The U.N. Human Rights Office concluded the boys “did not seem to pose any concrete threat to the Israeli forces” when they were shot.

By midafternoon, the raid was over.

The IDF announced it had killed two militants, Muhammad Zubeidi and Hussam Hanun, after surrounding the building in which they were holed up and firing shoulder-fired missiles, grenades and explosives. Israeli forces arrested another 17 “wanted suspects,” and confiscated weapons found in home searches, the statement said.

The soldiers took the two fighters’ bodies, according to camp residents, so their families could not hold funerals. Residents also said that the IDF misidentified one of the militants and that he was named Wissam Hanun.

A young girl sits in a house damaged by an Israeli blast in the al-Damaj neighborhood in the Jenin refugee camp on Nov. 30, 2023. (Lorenzo Tugnoli for The Washington Post)

The return

Shortly after sunrise on Thursday, Ahlam and her family roused themselves to head home. Rose slung her backpack over her shoulder. Ahlam emerged from the cottage in distress, hyperventilating as she walked toward the car.

The family was relieved to find their house still intact. But Ahlam headed straight to her bedroom, moaning from stomach pain that left her unable to speak.

Razan, a spunky seventh grader who likes Doja Cat and learning TikTok dances, sat on the floor, stringing together a beaded bracelet — skipping the first of her online classes.

During a midday raid in November, she was among hundreds of children trapped inside schools for hours, without food, until the United Nations persuaded Israel to call a 30-minute cease-fire to evacuate them.

Ahlam hasn’t sent her children back to their classrooms since then. “Security is more important than education,” she said.

The four UNRWA-run schools in Jenin, as well as others, have tried to keep classes going online, using techniques honed during the coronavirus pandemic. But access to internet is unreliable in the camp. And even before the raids ramped up last month, children in Jenin had already lost “many, many days of school because of military actions there,” Bouloukos said.

Rose is trying her best to keep up, even as she watches classmates grow distracted by fear or grief. On Thursday morning, she tuned into Arabic class from her phone in her living room. The lesson that day was on a poem by the late Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan, called “Martyrs of the Intifada,” a lament for the young stone-throwers of the first Palestinian uprising which began in 1987.

“They died standing / Blazing on the road / Shining like stars / Their lips pressed to the lips of life,” Rose read aloud.

Next came history class — Rose’s favorite — and a lesson on 20th-century anti-colonial struggles.

“We are studying war, but we are in it,” she said, looking up from her phone.

On Thursday, Samir al-Ghoul, 50, a father of seven, stood before what used to be his two-story house in the al-Damaj neighborhood. The two militants who were killed had hidden out there during the raid, putting Samir’s whole family at risk. At 5 a.m. on Wednesday, he said, Israeli forces began firing explosives at the house.

“We raised the white flag. They let us go outside the house, and I sent my kids to my brothers’ homes,” he said.

Israeli snipers then shot the militants as they fled.

“The situation is very bad, it is worse than before. [The Israelis] are taking revenge on us because of what happened on October 7,” Ghoul said.

On the roof of one damaged house, a 7-year-old girl with a pink headband bent down to pick up bullet casings and handed them, smiling, to a Post reporter.

About a dozen women gathered at a local community center Saturday to trade stories of that week’s raid and tips to protect their children. The younger ones held toddlers on their laps.

The facilitator passed out balloons for an exercise meant to treat anxiety. Imagine, she said, “the stress is all inside these balloons.”

One by one, the women shared their fears and sorrows:

“My psychological and physical health.”

“We hope to go back to our houses.”

“No one is left to protect the camp.”

A moment later, pop-pop-pops resounded around the room — this time, the sound of deflating balloons.

Hazem Balousha in Amman, Meg Kelly in Washington and Lior Soroka in Tel Aviv contributed to this report.