The Israeli government announced in a statement released in the early hours Wednesday that it had approved a hostage release with militant group Hamas.

At least 50 women and children taken hostage will be released over four days, the statement said, during which there will be a pause in fighting as the hostages surface from the group’s hideouts and underground warrens in Gaza where they have been held. Before the truce was approved, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said “the war will continue” even after a deal.

Whatever happens next, nothing can erase the trauma already unleashed. Hamas’s Oct. 7 shocking attack on southern Israel was the bloodiest single day in the history of the Jewish state and broke the uneasy, arguably unsustainable, status quo that existed between Israel and the Palestinians. In response, Israel has carried out a campaign to wipe out Hamas that is unprecedented in its scale, reach and devastation. More than 11,000 Palestinians have been killed in Israeli bombardments, many of them children.

The bulk of the Gaza Strip’s over 2 million people have had to flee their homes. The territory’s population in the north was ordered to evacuate to the south by Israeli authorities, sparking a panicked exodus. Israeli strikes hit targets across Gaza, but this weekend, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant indicated that the focus of their operation may be shifting further away from hollowed-out Gaza City in the north toward Khan Younis in the south, where Israeli authorities claim Hamas’s main command structure may be.

“People who were on the western side of the city have already encountered the [Israel Defense Forces]’s lethal strength,” Gallant told Israeli radio. “People who are on the eastern side understand that this evening. People who are in the southern Gaza Strip will understand that soon as well.”

Even if the fighting stopped today, huge swaths of Gaza have been reduced to rubble. According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, which cited data from local authorities in Hamas-controlled Gaza, some 45 percent of all of Gaza’s housing units have already either been destroyed or severely damaged. By one measure, it took four years of conflict in Syria to destroy a comparable share of what Israel pulverized in a matter of weeks.

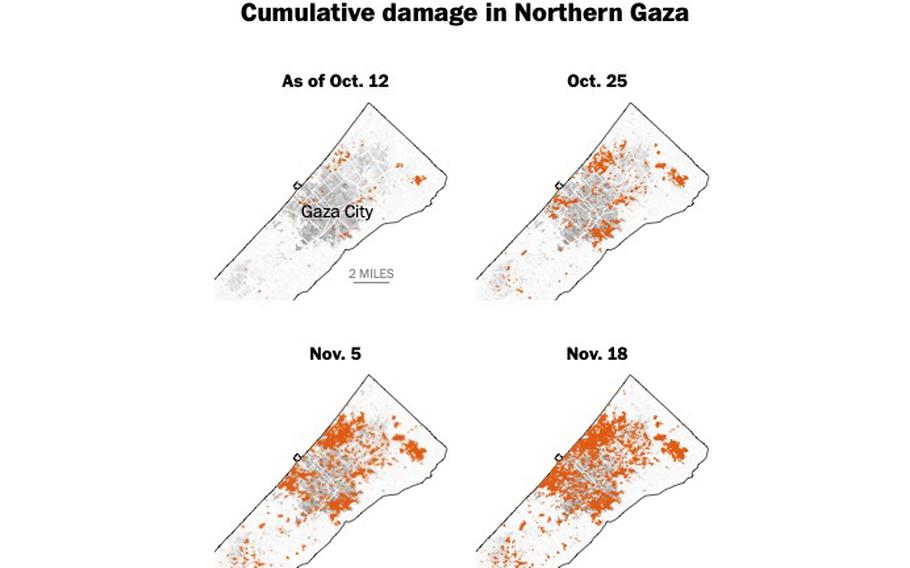

Israel dropped thousands of munitions daily on targets across Gaza, but especially in the territory’s north. The city of Beit Hanoun, once home to more than 50,000 people, is a ruin where “barely a single inhabitable building remains standing,” according to a visiting Israeli journalist earlier this month. Satellite imagery and drone footage show how the town’s once crowded, bustling streets are now a moonscape of debris and blasted buildings. Researchers examining satellite evidence estimate that perhaps more than half the buildings in north Gaza are damaged.

All the while, a humanitarian crisis teeters from bad to worse. Many Palestinians in Gaza are encamped in makeshift tent cities or crammed into U.N.-administered facilities, some of which have still been struck by Israeli bombardments. Critical infrastructure — from hospitals to desalination plants to fuel depots — are failing or shuttered. U.N. officials warn of the growing toll of hunger and disease stalking the territory.

In a Tuesday interview with CNN, U.N. relief chief Martin Griffiths described the situation in Gaza as the “worst ever” he has seen in a long career as a humanitarian official. “Nobody goes to school in Gaza, nobody knows what their future is. Hospitals have become places of war, not of curing,” he said. “No, I don’t think I’ve seen anything like this before.”

It’s difficult to calculate the costs of reconstruction. An 11-day war over Gaza in 2021 saw 2,000 homes destroyed and some 22,000 housing units damaged, and required more than $1 billion in foreign funding to aid recovery efforts. That’s a drop in the bucket for the current requirement, whenever hostilities truly cease.

“Although Gaza has a long history of conflict, there are no parallels to the scale of the present devastation,” explained The Washington Post’s Adam Taylor. “Some Palestinian officials put the economic cost of Israel’s ground operation in Gaza in 2014 at more than $6 billion. The current war is already longer and far more destructive.”

(The Washington Post)

Neither Israel nor its Arab neighbors have much interest in repeating earlier cycles of conflict, destruction and reconstruction. Gaza’s economy has cratered after more than a decade-and-a-half of Israeli blockade on the territory, which restricts the movement of goods in and the movement of people out. If, as the U.S. government expects, some normalcy is to be restored under a new Palestinian-led administration in the territory, a tremendous amount of foreign investment is required.

Many in Israel are not concerned about what comes after at this point, given the widespread desire to neutralize Hamas after what it inflicted on innocent Israeli civilians. Some politicians on the Israeli right, including ministers in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s cabinet, want to exact an even deeper toll on Gaza’s population. On Monday, far-right finance minister Bezalel Smotrich said Israel should “collapse the state system” in Gaza, a call, effectively, for more civilian suffering and destruction. He also echoed a suggestion by a former Israeli general to pursue the starvation of Gaza’s people, and to allow for the spread of disease in their ranks.

Israeli authorities are not taking a similar line, though Netanyahu has rejected the prospect of a political administration run by the enfeebled Palestinian Authority — which itself doesn’t want to be seen entering Gaza on the backs of Israeli tanks. But Israelis may have to eventually reckon with the desolation they’ve wrought.

“Even the great majority of Israelis who don’t dream of resurrecting Gush Katif have very little empathy for the suffering of Gaza’s residents,” wrote David Rosenberg in Haaretz, referring to the visions of the country’s radical settler movement. “Even if third-country donors pay for the lion’s share of the cost, it will be hard to accept with equanimity that we must have a hand in helping Gazans rebuild their homes, schools and infrastructure and in creating jobs for them — and inevitably, many of these jobs will have to be in Israel itself because Gaza cannot generate enough itself for the foreseeable future.”

And those third-country donors face tough questions, as well. “Arab officials do not want to clean up Israel’s mess and help it police their fellow Arabs,” reported the Economist’s Gregg Carlstrom from the sidelines of a regional conference in Bahrain. “But they also do not wish to see Israel reoccupy the enclave, and they admit, at least in private conversations, that the Palestinian Authority is too weak at present to resume full control of Gaza. If none of those options is realistic or desirable, it is not clear what is.”