Middle East

How government neglect, misguided policies doomed Libya to deadly floods

The Washington Post October 6, 2023

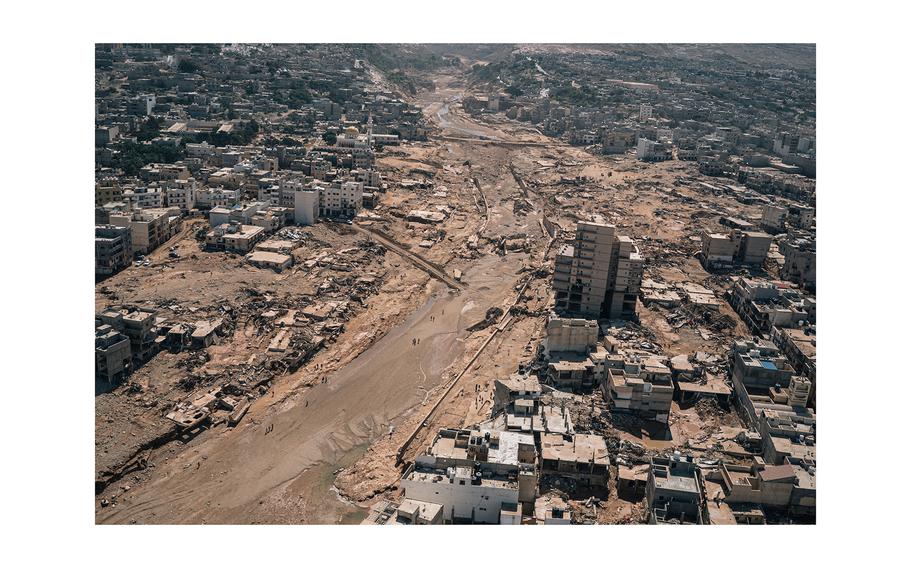

An aerial view of the damage in Derna. A strict curfew required people to shelter in place during the floods. (Alice Martins for The Washington Post )

The rains lashing Derna gave residents a sense of comfort as night fell on Sept. 10. Windows steamed up as dinners warmed on stovetops. Children curled up with their parents and watched cartoons long past their bedtimes.

A 30-year-old store owner, Mohamed BinKhayal, texted his brother from a few blocks away to see whether he needed help. He said he didn’t. He had obeyed government orders to shelter in place, like thousands of other families in the heart of the city. They thought they would be safe at home, away from the water’s edge.

“It’s just rain,” Mustafa, a father of five, texted back.

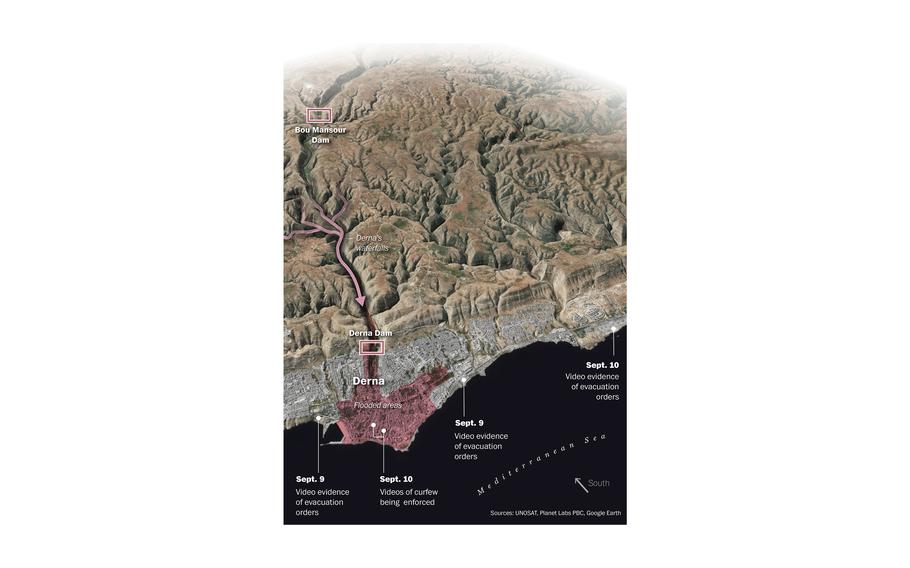

But it wasn’t. Authorities in both of Libya’s rival governments had known for days that Storm Daniel was coming, and for years that the dams above the city were damaged and at risk of collapse. Yet officials loyal to military commander Khalifa Hifter, head of the eastern government based in Benghazi, appeared never to consider the threat, believing instead the worst of the flooding would come from the sea.

Video evidence shows several evacuations being carried out among coastal communities in Derna, which prompted many people to move inland - and into the path of the coming flood. A strict curfew, enforced by armed security personnel, required people to shelter in place. Multiple generations of families gathered together and were washed away.

Warnings that the dams were filling up circulated among officials in the Ministry of Water Resources, which is responsible for water infrastructure and is part of the western government in Tripoli. They were not shared publicly until water had engulfed the city - too late for Mustafa BinKhayal and so many others.

“Coastal areas were evacuated because they expected those to flood,” said Ahmad Shawli, an official on Derna’s Emergency Response Committee. “People felt that the dam would protect them from flooding, so there was no urgency for them to flee.”

More than 12,500 people from the area are dead or missing, according to the World Health Organization. Residents and local activists believe the true number is far higher. Government restrictions have made it difficult for reporters to access the city in recent weeks. Protests calling for accountability ended in arrests.

This account of the final days and hours leading up to the disaster is based on more than two dozen interviews with residents, officials and experts, as well as videos, social media posts and documents reviewed by The Washington Post.

The former mayor of Derna, since relieved of his duties, as well as water management and other government officials in Tripoli did not respond to phone calls or text messages seeking comment. Efforts to reach Hifter through senior military officials were unsuccessful.

Derna is built on the ruins of an ancient Greek colony and its oldest families trace their lineage back to Andalusian times, when Muslims ruled modern-day Spain. It was home to Libya’s first theater troupe and has a rich intellectual history.

More recently, it has been caught up in the country’s brutal civil conflict, occupied by Islamist groups and pummeled by government forces. After a months-long siege, Hifter took control of the city in 2018. In the years that followed, both the air force that Hifter commands and the militia led by his son Saddam have been accused by Amnesty International of routinely targeting, harassing and torturing their critics in Derna. Neither Hifter nor senior officials in Tripoli have responded to the allegations.

In the mountains above the city, the Derna and Bou Mansour dams, built in the 1970s, had been damaged for decades. It was a “dangerous situation,” according to an unpublished 2006 study from the Ministry of Water Resources, later cited by Libyan academics who reviewed it.

A report from the Tripoli-based Audit Bureau, submitted as part of an ongoing government investigation into the dam collapses, concluded that authorities in Tripoli failed to carry out even basic repairs. Instead, the report says, they overpaid a Turkish company by 4 million Libyan dinars for dam maintenance between 2007 and 2010 - without encouraging them to finish the job or attempting to recover the funds when the project was left incomplete.

The report was obtained, verified and shared with The Post by the Sentry, a Washington-based investigative group.

While Libyan authorities have blamed the stalled maintenance on a popular uprising in 2011, the documents say that, after months of unexplained delays, work “stopped completely at the end of December 2010.”

The Ministry of Water Resources had ample money to fix the dams in the years that followed, the report concludes, including 459 million dinars in development funds in 2021 alone.

Last year, a study by hydrologist Abdelwanees Ashoor concluded that the situation in the Wadi Derna basin required immediate action. “In the event of a huge flood, the result will be disastrous,” he wrote.

The dams were a preoccupation for Ashoor, who had warned of their fragility as early as 2008 in his master’s thesis. When he returned to Derna last year, he told The Post, he found “the amount of surface runoff had increased and the probable maximum flood had increased because of conditions and soil runoff and the lack of vegetative cover.”

Trying to deliver those warnings to Libyan authorities felt like “whistling in the ears of the dead,” he said.

More than 12,500 people from the Derna, Libya, area are dead or missing, according to the World Health Organization, after massive flooding in early September. ()

Officials told The Post they did not consider that heavy rains could overwhelm the dams, or take steps to prepare for such a scenario.

“The situation in Derna looked very normal, there were no indicators that it would be a crisis,” said Mohamed Douma, the water minister of the Benghazi-based government in eastern Libya. But he conceded: “This is not an excuse for the amount of neglect that happened with the maintenance of the dams.”

As Storm Daniel approached, officials across eastern Libya held a flurry of crisis meetings, according to social media posts and accounts by officials. In Derna, a committee led by the head of the city’s security directorate decided to evacuate several neighborhoods close to the waterfront - well outside the eventual flood zone.

A Sept. 9 order signed by eastern Libya’s prime minister, Osama Hamad, declared a two-day holiday and told residents to limit their movements along roads.

Workers from the local water and sanitation company started clearing drainage outlets with excavators along the coastline. Boy Scouts helped to evacuate a hospital and cleaned the streets.

Red Crescent ambulances and police cars fanned out across waterfront neighborhoods, warning residents to leave. But in many instances, the authorities offered them no place to go. Families piled into cars, locals said, and headed inland to apartment blocks already filled with people waiting to ride out the storm.

From his shoe store, Mohamed BinKhayal watched the warnings loop across television screens and social media as he tried to focus on work. He locked up the store when he heard the police cars urging his district to shelter in place, slamming the blue shutters closed. “It’s probably best to be at home,” he recalled thinking as he climbed in his car and headed out.

The voluntary coastal evacuations continued on Sept. 10. So did the curfew. Residents argued over whether to stay or go. Some didn’t trust the weather reports; others didn’t trust the authorities.

Derna’s municipal council announced on Sept. 10 that the city would be shut down from 7 p.m. that night until 8 a.m. the next morning.

On social media, government accounts simultaneously urged people to evacuate their neighborhoods and to obey the curfew. On the streets, a video shows armed security forces walking alongside emergency vehicles as loudspeakers blared: “All citizens must remain in their houses.”

“A curfew would clear the roads for emergency vehicles and such,” said Douma, the water minister, explaining the government’s rationale.

Abdul Gader Faraj, a nurse in Derna, was starting to worry about his family. He was 700 miles to the west, in Misrata, where he had taken their eldest son for cancer treatment. His wife, Fatima, and their other two children had been told to evacuate their home on the coast in Derna. He was relieved when Fatima called her father to come pick them up, as the sun sank in the sky and the wind harried the trees on the seafront.

Their neighbor, Ali, took his wife and children to his in-laws near the center of the city, Faraj said, then went to shelter with his parents further up in the valley.

Videos from later that evening show emergency vehicles trying to make their way through the driving storm. Boy Scouts were still cleaning the valley in the dark, their yellow raincoats fluttering in the wind.

In interviews after the storm, families described sheltering in place, steeling themselves for a long night. Children packed onto sofas and stretched out on living room floors, some excited to be with their cousins for a sleepover, others overtired and tearful. Parents stirred dinner pots and prepared school bags for the new term.

On a street running down to the seashore, 43-year-old Abdulrazzak Mustafa stepped outside briefly to check on the rains, then slipped back inside. His two youngest children had fallen asleep in front of the television. He picked them up gently and carried them to their beds.

Abdulrazzak Mustafa’s phone barely stopped ringing through the swelling storm, as nervous relatives across the city checked in again and again. Shortly before midnight, Mohamed BinKhayal texted his brother Mustafa to see if he needed help. Abdul Gader Faraj called his wife. Everyone, it seemed, was safe.

“The incomprehensible part of this entire tragedy is the curfew imposed by the Derna security directorate from the start of the storm,” said Hanan Salah, associate director of the Middle East and North Africa division of Human Rights Watch. “This effectively trapped people in their homes and from then on, they stood no chance.”

Around midnight, the cellphone network crashed and the power failed. Derna was plunged into darkness. Every family’s world shrank: “Suddenly, no one knew anything about anyone else,” Abdulrazzak Mustafa said.

At the Wadi Bou Mansour dam, there was only one guard on duty that night, according to Claudia Gazzini, the International Crisis Group’s senior analyst for Libya, who interviewed him and officials in Tripoli’s Water Resources Ministry for a recent report.

Destroyed houses and buildings in central Derna are partially buried in mud after the deadly flooding last month. (Alice Martins for The Washington Post )

The rain had reached a frightening intensity by midnight. Water was rushing down the valley into the center of the city, spilling over into adjacent streets. The dam was filling up. The guard told Gazzini he called his immediate supervisor at the Water Resources Ministry in Derna, who relayed the warning to Benghazi.

An official at the ministry in Benghazi told her that he notified Tripoli of the worsening situation.

At 1:12 a.m. on Sept. 11, a message was posted on Facebook, but the intended recipients were already cut off from the outside world.

“The Ministry of Water Resources in Tripoli assures citizens that the Derna dam is safe and that rumors about it being broken are false,” the message read. “The dams are in good condition and things are still under control.”

By this point, they said they had already lost contact with the dam’s supervisors in Derna.

Residents used different words to describe the sound they heard around 3 a.m. Some called it a boom, others a roar. One man said it sounded like the horizon had “popped.” Security camera footage shows a wave rushing so fast through the streets that it dragged cars along with it. Entire houses were carried into the sea and asphalt was ripped from the sidewalks.

Abdulrazzak Mustafa struggles even now to understand the strength he mustered in that moment, forcing their door shut against the wave as he held his screaming children above him. Water had poured through the window and was rising past his chest.

“I couldn’t think of myself, I knew I was going to die, he said. “All I could do was pick them up and try to save them.”

Mohamed was trying his brother’s cellphone again and again, but getting nothing.

In neighborhoods with lower tides, people slipped in the streaming mud as they tried to flee, straining against wind gusts that knocked them backward. Some parents lost children underfoot, or tripped over bodies in the scramble.

Hospitals that still functioned were inundated. One medic saw 100 patients in the first hour. By daylight, it was closer to 1,000.

Across Libya, rumors of a tragedy were spreading, but Derna was still in blackout. At 2:39 p.m. on Sept. 11, Derna’s municipal council confirmed on Facebook that the dams had burst.

As the sun came up on the city, the scale of the damage was almost unimaginable.

Mohamed finally found his brother Mustafa BinKhayal dead in the crush of his home. Across the road, another 20 of the brothers’ immediate relatives - all sheltering in place together - had drowned.

Faraj’s wife and children survived, but their neighbor, Ali, who had evacuated his family to stay with their relatives, learned that he had taken them right into the path of the flood. When Faraj called to offer his condolences, the man could barely speak through sobs. “He brought his own kids and wife to death by his own hands,” Faraj said. “He was trying to keep them safe.”

An official in the Tripoli-based agricultural ministry, Riyadh Jouha, agreed that people were not adequately warned of the dangers. But he said they were partly at fault for having built their homes along the river.

“They shouldn’t just blame the government altogether, they should blame themselves too,” he said.

Among the dead were several police officers and Red Crescent workers involved in the curfew and evacuation efforts, according to witnesses and social media posts. More than 100 medical personnel were killed.

“So many lives were lost that day, and the people of Derna deserve in the very least to know why authorities who are meant to protect them failed them so miserably,” said Salah, of Human Rights Watch.

4,267 people have been buried. Another 8,500 people are missing and presumed dead. Some families are still asking for news on Facebook, clinging to hope. “There were two people who saw him, but we haven’t found him,” wrote a woman looking for her husband.

On his own page, Mohamed BinKhayal said the pain was now greatest for the living. “It is the ones who survived in Derna who died,” he wrote.

Heba Farouk Mahfouz contributed to this report.