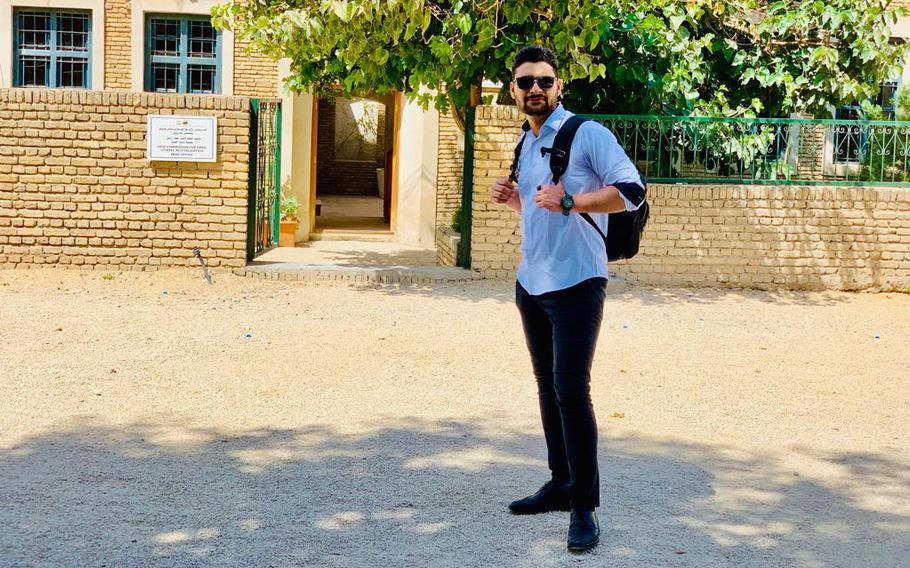

Niyam Alami, who fled Afghanistan in 2021, is now in Iraq and has spent two years waiting to reunite with his family pending a decision on his U.S. visa application. In 2022, he attended a workshop for journalists and activists in Erbil, Iraq. (Niyam Alami)

The desperate evacuations from Afghanistan two years ago amid the collapse of the U.S.-backed government sent tens of thousands of refugees on journeys across the world, many of whom turned to the country whose forces they had helped.

For them and the U.S. veterans and advocates seeking to resettle them, the past two years have been filled with fear and uncertainty as well as with rare but cherished victories.

Niyam Alami still remembers the chaos in Afghanistan in August 2021, when he and his family rushed to the Kabul airport in search of a flight out as the Taliban overran the country with an alarming speed that caught Washington unaware.

At the airport, they could not find their way through a crowd of thousands, so they retreated. In October of that year, Alami was separated from his family, he said.

He took a flight out of the country and into Iraq, thinking his stay there would be a temporary stop and that he could finish his education. His family found another flight, which brought them to Kansas.

But an indefinite wait for a decision on his U.S. visa has prevented him from being reunited. He said he speaks regularly with other Afghans scattered across the world: a friend in Qatar, another in Kyrgyzstan, a few dozen who are with him in Iraq.

These conversations often start with wistful nostalgia for their homeland before delving into their present circumstances.

“The issue on our minds these days, the thing that takes over discussions and conversation is what’s going to happen to us,” Alami said.

One of his friends told him recently, “The uncertainty is killing me,” he said.

Like many other Afghans, he fears retribution for working with the U.S. military and civil society organizations during the failed 20-year-long American project to fight terrorist groups and develop democracy in Afghanistan.

He was a student at the American University of Afghanistan and worked as a researcher documenting the war between the Taliban and the country’s U.S.-backed military.

The Taliban have imposed harsh restrictions on the rights of women and girls and have increased detention of journalists and other critics since returning to power in 2021, a statement last week by Human Rights Watch said.

Their security forces also have detained, tortured or executed former members of the U.S.-backed security forces, as well as suspected members of armed resistance movements, the New York-based advocacy group said.

Niyam Alami was a student at the American University of Afghanistan prior to 2021. He fled to Iraq and completed his studies there. However, the rest of his family went to the U.S., and he has been separated from them for the past two years. (Niyam Alami)

Veterans still feel it vividly

These acts of violence often show up in the email and social media accounts of U.S. military veterans.

“You wake up day after day and you start out in the morning by looking at your inbox, and it’s filled with messages like, ‘Please help me, I’m going to die,” said Alex Plitsas, a veteran who volunteered with an effort called Digital Dunkirk.

Plitsas is one of the thousands of veterans who participated in the ad hoc volunteer campaign to resettle Afghan allies after the Taliban took over.

He said he felt a sense of moral obligation not to abandon people who worked with him and the U.S. military.

But like other veterans and civilian resettlement advocates, he expressed deep frustration about what they say is the slow pace of finding visas for Afghans who need them.

“I’m exhausted,” Plitsas said. “I think everybody else is, too. You know, we were hoping to not still be doing it at this point, but unfortunately, we are.”

Burnout among veterans and resettlement advocates has been common, he said.

The reasons range from lack of time to volunteer to lack of money to donate to loss of hope in trying to navigate a byzantine immigration process on behalf of people halfway across the globe, Plitsas and other veterans said.

“It feels like a brick wall that you can’t get through,” said Pete Lucier, who worked with a group known as the #AfghanEvac coalition.

Lucier said one of the groups he worked with once had 200 volunteers but since has shrunk to a core of 15 to 20 people.

What keeps them going after two years is the rare triumph, Lucier said.

The small victories include helping an Afghan translator progress on a visa application or finding out that an Afghan in need is on a plane to the U.S. or meeting a family that has settled into a new home, veterans and advocates said.

“Seeing those stories is one of the ways that we are able to prevent burnout,” Lucier said. “It reminds us that all this work is this incredible privilege.”

Refugee perspective

Some of the Afghans who made it to the United States shared a similar sentiment, with seemingly mundane achievements buoying their spirits.

Taqwa Kandahary, once a doctor in the Afghan military, said she recently learned to drive. Her journey two years ago took her from the chaos of the Kabul airport to Qatar, Germany and finally Virginia.

The happiest day of her life was the day she arrived in America, Kandahary said. But in July, she also experienced one of the lowest points stateside, when she was hospitalized.

With her family still in thousands of miles away in Afghanistan, she felt the loneliness.

The driver’s education class she took was provided by the resettlement group Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area. In addition to the driving instruction, it helps refugees develop entrepreneurship and learn about American culture.

Kandahary said she never learned to drive in Afghanistan because of cultural restrictions on women there. But she soon felt more confident being able to move around on her own.

After passing the course, she even went a step further, obtaining a commercial driver’s license.

“I knew that being a truck driver was going to be difficult, but I wanted to put myself in a difficult situation,” Kandahary said, adding that she hopes to be a full-time truck driver soon.

In the meantime, she also faces uncertainty and fears as she waits on her asylum case. But she believes that the travails of the past two years will pay off.

“Now things step by step are becoming better,” Kandahary said.