U.S. soldiers score big with the Iraqi children of the Isla Zeral neighborhood of Mosul in 2005, as the kids call out for candy or soccer balls. (Stars and Stripes)

Michael Ashby got out of the Army after injuries from seven roadside bomb blasts in Iraq caught up with him.

One explosion slammed him into the ceiling of his armored vehicle and ruptured his neck vertebrae, an injury he calls his Iraqi souvenir. The blast left him a half-inch shorter.

Ashby, 46, considers himself lucky. He has friends who didn’t survive Iraq, either while deployed or after they came home.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq 20 years ago evokes complicated and often bitter emotions, and questions of whether the war was worth it sparked a wide range of responses from U.S. veterans and Iraqi citizens.

Most accounts hold Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of people, including ethnic cleansing campaigns against the Kurds in the country’s north.

But the removal of Saddam and the operations of the past two decades have cost the lives of 4,599 U.S. troops in Iraq, according to Pentagon figures. That’s in addition to coalition-nation deaths and anywhere from 276,000 to 308,000 war-related Iraqi deaths, according to Brown University’s Costs of War project.

Despite the well-recounted early failures in planning that led to insurgencies and a host of other problems, some U.S. service members were more hopeful about Iraq’s future toward the end of combat operations in 2011 than the U.S. public, as reflected by opinion polls.

Ashby, who trained Iraqi soldiers, had been optimistic about the nation’s prospects.

“I’m excited to see what the Iraqis can do, actually,” Ashby told Stars and Stripes in 2011 while serving as a sergeant with the 115th Brigade Support Battalion, 1st Cavalry Division. He believed then that the U.S. war in Iraq was worth it, adding, “It better be.”

It was the Iraqi military’s failure against the Islamic State group in the ensuing years that shook Ashby, who did four tours in Iraq.

“All that effort to train these soldiers, then we watched them throw up their arms and run,” Ashby said in a recent call.

Some of that was attributable to corruption in the heavily centralized Iraqi military structure. Officers in Anbar province, where ISIS made fast gains, told Stars and Stripes in 2011 that Baghdad had sent them barely any bullets and training gear.

Ashby has struggled with what his service meant. He sometimes goes out of his way to avoid hearing about Iraq. Was the war worth it? He said he no longer knows.

“I used to think about it a lot,” Ashby said. “I don't think about it anymore. It baffles me.”

Some veterans contrasted the optimism they had that the U.S. could make Iraq a better place with their horror at the violence that followed.

Kayla Williams, a former Army linguist, recalled breaking down in tears after watching news reports of the 2007 terror attacks against ethnic Yazidis. She wondered if the victims were the same people who gave her tea as she talked about the virtues of democracy on her deployment during the invasion.

“The U.S. with all our intel and all our smart people, we didn't see it coming, and they suffered,” said Williams, 46, who now works at Rand Corp. as a researcher.

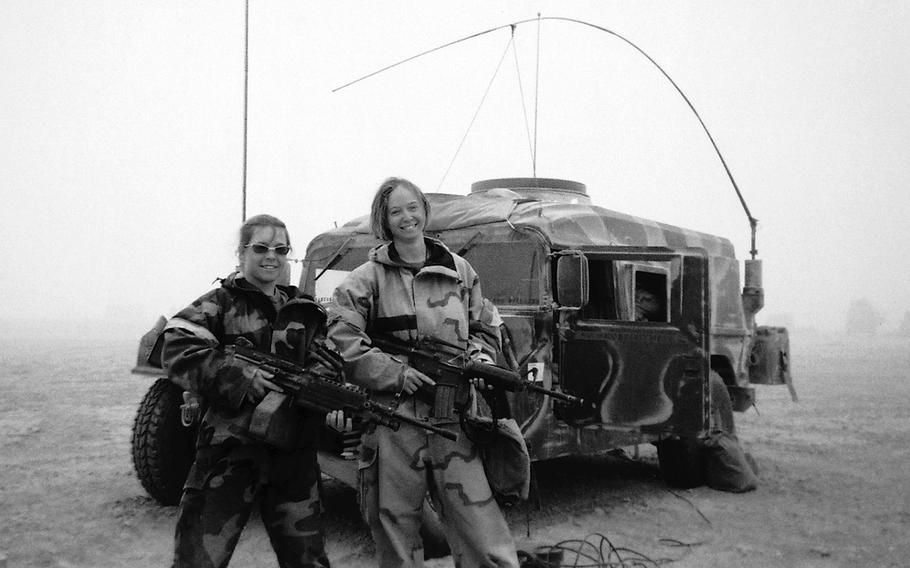

Kayla Williams, right, and another soldier during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. (Kayla Williams/Special to Stripes)

Others find value in the lives that they saved, personal connections and the broader meaning of service.

“History can conclude that this was a tortured campaign — but it can never conclude that our people did not do the job the nation asked,” Joseph Votel, a retired general who helmed U.S. Central Command from 2016 to 2019 and is a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, said in an email.

Gen. Joseph Votel, then commander of U.S. Central Command, meets troops at Qayyarah West Airfield, Iraq, Oct. 25, 2016. Votel, now a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, says troops should not be judged on the outcomes of decisions made above their level of control. (Christopher Brecht/U.S. Army)

Most Americans made up their minds about the Iraq War long ago. Only 14% view the war as a success and 52% believe it was a mistake, according to a 2,000-person survey released Wednesday by the U.S. bureau of research group More in Common.

Hopes for the future

Some Iraqis said they hold the U.S. responsible not only for the sectarian violence after the invasion but also for the rise of ISIS.

Ammar Rashed, a former translator, said he helped American troops target some of the country’s most vicious militia leaders. Then those warlords joined the parliament that the U.S. created.

Rashed said he fled the country in 2021 after one of his co-workers disappeared.

Rashed, 39, is in Jordan. He has waited five years for a U.S. Special Immigrant Visa and is among about 100 others from Iraq with pending cases, according to the New York-based International Refugee Assistance Project.

He said his hope for a peaceful Iraq ended when U.S. troops withdrew in 2011. He once felt like he was doing the right thing helping American troops, but now he has doubts.

“I don’t want to regret that I’ve done this,” Rashed said.

Raed Ibraheim, 34, recalled the hope he felt in 2003. He approached U.S. troops on their patrols so he could practice his English.

But Ibraheim’s optimism soon faded. A car bomb shattered the window of his home. He hid from a gunfight in the bushes of a playground.

Ibraheim fled Iraq in 2008 and is now a U.S. citizen. He wonders whether he ever can go home.

"It's still painful to think about,” Ibraheim said.

There’s a battle in Iraq for the way people remember the war, said Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, 47, a journalist from Baghdad who has reported on his country over the past two decades.

Even the term people use to describe the U.S. presence has changed over time.

“Everyone calls it an occupation right now, even the people who benefited from it,” Abdul-Ahad said.

Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, an Iraqi journalist, stands in Istanbul, Turkey, in June 2022. Abdul-Ahad, who began working as a reporter in 2003, wrote a book on his experiences over the last 20 years: “A Stranger in Your Own City: Travels in the Middle East’s Long War.” (Rena Effendi/Special to Stripes)

Like others in Iraq, Abdul-Ahad said he saw the U.S.-led coalition’s mistakes pile up: the lack of a plan after toppling Saddam; policies that disproportionately removed Sunnis from the government and the military; the inability to bring order to the cities or prevent terrorists from crossing into the country; and war crimes like the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

The worst part of the past 20 years has been how American failures in nation building tarnished the concept of democracy, Abdul-Ahad said. Autocratic leaders cite what happened after 2003 as proof against reforms, and many young people wonder whether Saddam was that bad, he said.

Still, some Iraqis believe their country has improved since the U.S. invasion. It’s safer than it was during Saddam’s dictatorship, said Saleh al-Assadi, 41, a native of Basra in southern Iraq.

Both al-Assadi and his son, Mahdi Saleh, said they recently cheered the arrival of the Arabian Gulf Cup to Basra as a sign of normalcy.

Mahdi, 17, is a striker for his soccer team. He barely remembers the war and has hope that Iraq has a bright future.

Mahdi’s right eye is missing, after a rocket attack hit his home when he was 4 years old. His father said insurgents fired the rocket, leaving shrapnel in his son’s brain, chest and back. He brought Mahdi to the nearby U.S. base.

A gruff American sergeant who worked at the gate helped Mahdi receive surgery in Heidelberg, Germany, through the Mercy Corps.

That sergeant, Paul Braun, remembers the day he got a call from Germany telling him that doctors had removed the shrapnel and saved Mahdi’s life.

Braun, 49, did two tours in Iraq. When he left in 2010, he thought Iraq was getting better, only for things to “go to hell,” Braun said.

But he believes his service in Iraq was worth it and hopes that Americans don’t forget the war.

Braun said he’s always receiving calls at random hours from Mahdi and others in Iraq. He helped a translator, nicknamed Philip Morris because of his chain-smoking, get to safety in America.

He even hosted Morris for three years in his house in Minnesota.

“If we could help someone like Mahdi, if we could help someone like Philip, at least I could feel a little bit of an accomplishment from that,” he said.

Iraq has better days ahead, Braun said. And one day, he hopes to come back to Iraq as a tourist and visit Mahdi in Basra.

Mourners hug after a 2007 memorial ceremony in Schweinfurt, Germany, for 2nd Brigade Combat Team soldiers killed in Iraq. Some 4,599 U.S. troops died in Iraq in the two decades following the invasion of the country in March 2003, according to Defense Department casualty figures. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)