KAMUNEH, Syria — When the deadly earthquake ravaged northwest Syria, it hit buildings weakened by constant fighting and people who had already been displaced many times in the country's decade-long civil war.

More than two-thirds of the inhabitants of Syria's rebel-held northwest enclave — nearly 3 million people — are from elsewhere in the country and were pushed to this remote corner by government forces, in some cases to squat in half-ruined buildings or olive groves.

Thousands soon found that buildings weakened by shelling from Syrian government forces and their Russian allies were no match for the tremors of the 7.8-magnitude earthquake and its host of powerful aftershocks that brought down houses right and left.

"When we left the house at 3:30 a.m., I swear we wandered in the streets, wherever there was clear space amid the water and rain and cold," said Abu Mwaffaq, a grizzled old man. "The ground floor completely disintegrated; we don't dare to go home."

A passing driver took pity on him and brought him to the comparative shelter of the provincial capital of Idlib, where tents have been set up for the newly displaced. "Where do we go? We have no idea," he said.

The squabbling collection of rebel groups that control the enclave had not exactly invested in building maintenance or earthquake preparedness. The situation in Idlib province was already desperate, and few places in the world were less prepared for a natural disaster.

For days, residents, many of whom were already surviving on foreign aid, have been crying out for humanitarian assistance and search-and-rescue support for their forgotten pocket. Finally on Thursday morning, a U.N. aid convoy crossed into the area through Turkey, the first since the earthquake.

Near the town of Sarmada, an area called Kamuneh has been taken over by tents; typically, they are set up as temporary shelter from the bombs that regularly rain on the area. Now they are host to those who have escaped the earthquake. Residents have been working on their own for days to set up new encampments. Their job is complicated by wind whipping through the rugged region, sending the blue and white tent fabric flapping wildly.

The men are used to setting up tents by now and work like a well-oiled machine. The metal skeleton is quickly assembled and then they unfold the tarp over it. Some hold the metal frame still as the others hammer on the fabric. The wind blows so hard that chunks of rock are placed on the tarp outside to stop it from flying away.

"Here, every day they tell us we have to leave. Every day," said Abu Mohammed. "They tell us we can go to other tents, but we can't stay here." His own house is actually still intact but he's afraid it might come down in an aftershock. But he doesn't want to go to one of the camps for the internally displaced, which he fears could become his permanent home.

He was awake when the quake hit, and felt everything shaking. "I was looking at the ceiling, thinking it's going to fall on me, there's no question about it," he said. His kids woke up and came to him crying. "We got dressed and went out and sat in the rain. You couldn't even sit by a building wall; you had to stand in the street where there is nothing."

Rescue efforts in Syria have been hampered by the war, which divided up the country into spheres of influence and left Idlib province and surrounding areas with only the international community to care for it. But until Thursday, the United Nations said the roads to the enclave were rendered impassable by the earthquake.

People have largely been left to dig out on their own. More than 1,900 have been killed there, and nearly 3,000 are injured, according to the Syrian Civil Defense that is funded by Britain and the United States, better known as the White Helmets.

In the aftermath of the quakes, surviving buildings were converted into shelters. Restaurants, wedding halls and schools opened their doors to those who lost their homes or could not return for fear that they would collapse — a fear that is renewed with every aftershock that shakes the area.

Abu Khaled spent a night in the rain after the earthquake, leaving his shattered house behind.

"I left without the martyrs that were still stuck under the rubble," he said. "We left with the clothes on our backs. Just look at me. All our things are gone. We're missing everything. Everything. Everything." He made a short list: bedding, mattresses, sources of heat.

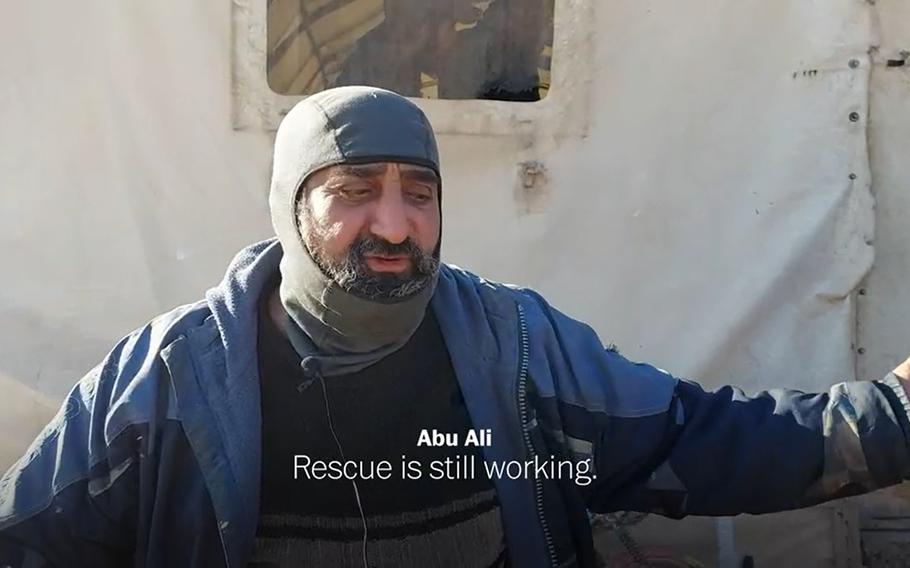

Food is only available for those who can afford to make a trip to the store, said Abu Ali, a heavyset bearded man wrapped up against the cold. "These people, these kids haven't eaten all day," he said. "I just took my wife to the clinic: There are no doctors."

His house was in Salqin, one of the towns most ravaged by the earthquake, and rescue operations are still underway. He is waiting for help, but is not hopeful.

"They just keep coming, filming us, and leaving, filming us and leaving. There is nothing else."

In this screenshot from video, Abu Ali, a Syrian man in Kamuneh, describes missing food and clothes following the powerful earthquake on Feb. 6, 2023, that struck Syria and Turkey. (The Washington Post)