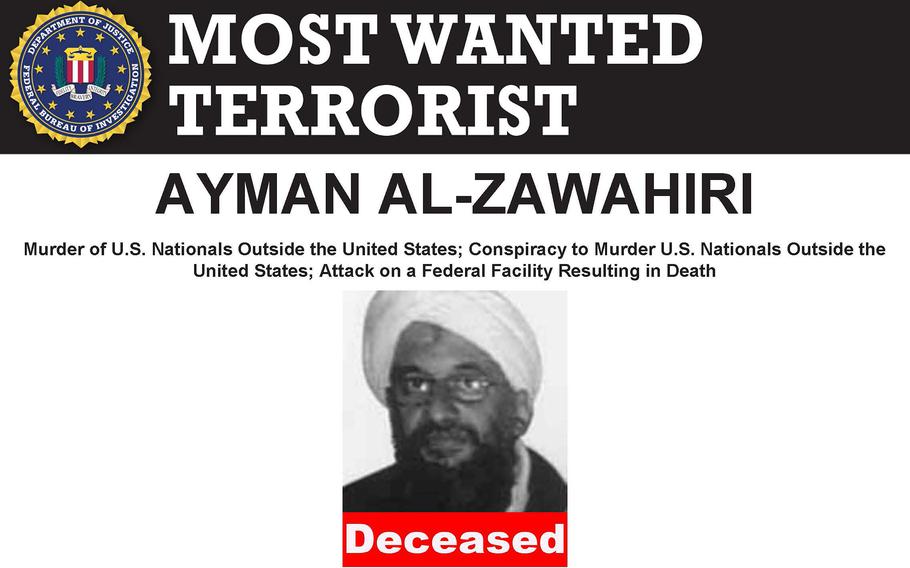

The word “deceased” has been added under the photo of Ayman al-Zawahri on wanted posters and the FBI website. The al-Qaida leader was reportedly killed by a U.S. drone attack in Kabul, Afghanistan, on July 30, 2022, U.S. officials said. (FBI)

The death of al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri following a U.S. drone strike on a safe house in Kabul may also mean the death of the Taliban’s chances to gain wide international recognition as a legitimate government willing to break with its sponsorship of global terrorism.

While it’s arguable whether Washington ever expected the Taliban to follow all the stipulations of the 2020 Doha Agreement, which led to the allied pullout from Afghanistan, the centerpiece of the deal was a Taliban pledge not to let extremist groups stage attacks against the U.S. and its allies.

Allowing in the leader of the group that staged the 9/11 attacks makes it far less likely that the Taliban, which is governing amid a foundering economy and widespread food shortages, will receive aid or see billions of dollars in state assets held by the U.S. unfrozen, analysts told Stars and Stripes.

“It makes it harder for those who have been preaching the virtues of engaging with the Taliban,” said William Maley, professor emeritus of diplomacy at Australian National University in Canberra.

“The Doha agreement is as dead as a doornail, but it can be a useful rhetorical device for each side to justify their positions,” Maley said.

The Taliban, who have not confirmed al-Zawahri’s death, on Tuesday accused the U.S. of violating the principles of the agreement by conducting the strike.

The day before, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the Taliban had sheltered the al-Qaida leader “after repeated assurances to the world that they would not allow Afghan territory to be used by terrorists.”

U.S. officials told reporters Monday that al-Zawahri had moved to Kabul after the Taliban retook the country last year. He was living in the upscale Shirpur neighborhood, home to several Taliban leaders who moved into the mansions of former high-ranking officials of the toppled Western-backed government, The Associated Press reported Tuesday.

U.S. officials added Monday that al-Zawahri, 71, continued to pose a threat to the U.S. by providing strategic direction to al-Qaida.

An MQ-9 Reaper armed with eight AGM-114 Hellfire missiles sits on the flight line before a test flight at Creech Air Force Base, Nev., in 2020. Al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri was killed by a drone firing a Hellfire missile in Kabul, Afghanistan, on July 30, 2022, U.S. officials said. (Haley Stevens/U.S. Air Force)

Some members of the Taliban undoubtedly knew of al-Zawahri’s presence in Kabul, said Antonio Giustozzi, senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London.

The Arabic-speaking al-Zawahri and his family would have been highly recognizable in Kabul and would not have come without some assurances of safety, Giustozzi said.

After years on the run, the al-Qaida leader was in failing health and may have wanted to be nearer to medical care, Giustozzi said.

The terrorist group had been keeping a low profile in Afghanistan at the behest of the Taliban, a Pentagon report in May said. According to the report, al-Qaida numbered about 200 people in Afghanistan and probably did not have the ability to attack the United States.

The group in Afghanistan is on a “declining global trajectory” and would need at least one to two years to rebuild to launch an attack on the West, Lt. Gen. Scott Berrier, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, told Congress in May.

Members of al-Qaida in Afghanistan said their relationships with the Taliban have been diminishing, Giustozzi said.

He said a researcher working in Afghanistan on his behalf spoke to an al-Qaida member in the eastern part of the country on Sunday.

In that interview, the al-Qaida member said the powerful Haqqani family, which fought semi-autonomously against the U.S.-led coalition, is among the terrorist group’s few close allies.

“The only people that they seem to be trusting is the Haqqanis, although they still have some doubts there as well,” Giustozzi said.

The house where al-Zawahri stayed belonged to a top aide to senior Taliban leader Sirajuddin Haqqani, a senior U.S. intelligence official said in the AP report Tuesday.

Members of the rival Islamic State group in Afghanistan will most likely accuse the Taliban in their propaganda of complicity or selling out al-Zawahri, analysts said.

During the first half of 2022, al-Zawahri reached out to supporters with video and audio messages, including assurances that al-Qaida can compete with ISIS for leadership of a global movement, a study by the United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team said, as cited by the AP report.

Born in 1951 in Egypt to a prosperous family, al-Zawahri was religiously observant at a young age and associated early on with violent movements seeking to overthrow the governments of Arab nations, analysts say.

He worked as an eye surgeon while traveling through Central Asia and the Middle East to meet with other insurgent groups. He was imprisoned and tortured following the 1981 assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, which biographers say led to his further radicalization.

He merged his own Egyptian militant groups with Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida, providing it with organizational skill and experience.

Following 9/11, he organized attacks throughout the world, including the 2005 London bombing, which killed 52 people, the AP reported. After bin Laden’s death, al-Zawahri took over the organization.

His successor in al-Qaida will most likely not be announced for a month or so, Giustozzi said.