(The Washington Post)

The five Syrians pulled from their homes by secret police on the same night last year were not insurgents, spies or suspected of being disloyal to the country's president, Bashar al-Assad.

Instead, they were targets in a desperate new phase of Assad's battle to survive: the hunt for cash.

All five were executives at Syria's second-largest cellphone company, MTN Syria, according to individuals familiar with the episode. Their arrests were part of a ruthless campaign by the president to seize MTN's assets, along with almost every other meaningful source of revenue in Syria's shattered economy.

MTN was ultimately brought to its knees four months ago after protracted pressure in which those arrests were followed by demands for multimillion-dollar payments, threats to revoke the company's operating license and a dubious court ruling that put an Assad loyalist in charge of the company.

The South Africa-based corporation announced in August that it was abandoning the Syrian market under conditions that its chief executive called "intolerable." MTN's cellphone towers are still working, its 6 million subscribers still paying their monthly bills.

"But where that money is going, no one knows," said a Syrian executive who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation. "Honestly, no one knows."

Similar events have played out repeatedly over the past two years, as Assad and his financially strapped regime have raided or outright seized dozens of businesses, including foreign corporations and family enterprises that rode out Syria's decade-long war in government-held territory, according to U.S. and other Western officials, as well as Syrians with firsthand knowledge of the regime's actions. Neither the Syrian government nor the Syrian presidency responded to requests for comment.

Companies that had survived the war have been raided by teams of regime "auditors" and agents, who scour their accounts for supposed tax and customs violations or other pretexts for hefty fines. Business leaders who stuck by Assad have been detained and pressured to cough up money to supposed charities that are widely seen as Assad slush funds.

The moves are part of what one Dubai-based Syrian executive called a "mafia-style money grab."

The most brazen cases amount to corporate decapitations in which top executives are forced out under duress and replaced by Assad loyalists. Among them is a relative newcomer, Yasar Ibrahim, who in a two-year stretch has acquired control of MTN and other Assad-targeted companies.

Even members of the Assad family have not been spared. Last year, Assad stripped his cousin Rami Makhlouf of companies and assets that had once been part of a massive portfolio estimated by Syria experts to be worth as much as $10 billion.

The regime's campaign to commandeer wealth has only intensified since then. U.S. officials and Syria experts said it has been driven by the intense financial pressure on a regime that has been bankrupted by war, daunting debts to Iran and Russia, a meltdown in neighboring Lebanon's financial sector and continuing economic sanctions from the West.

Assad needs the money, officials and experts said, to meet payroll for his military and security services, to buy fuel and food for the capital and other areas still under regime control, and to reward some Syrian elites who remained loyal to him through the war.

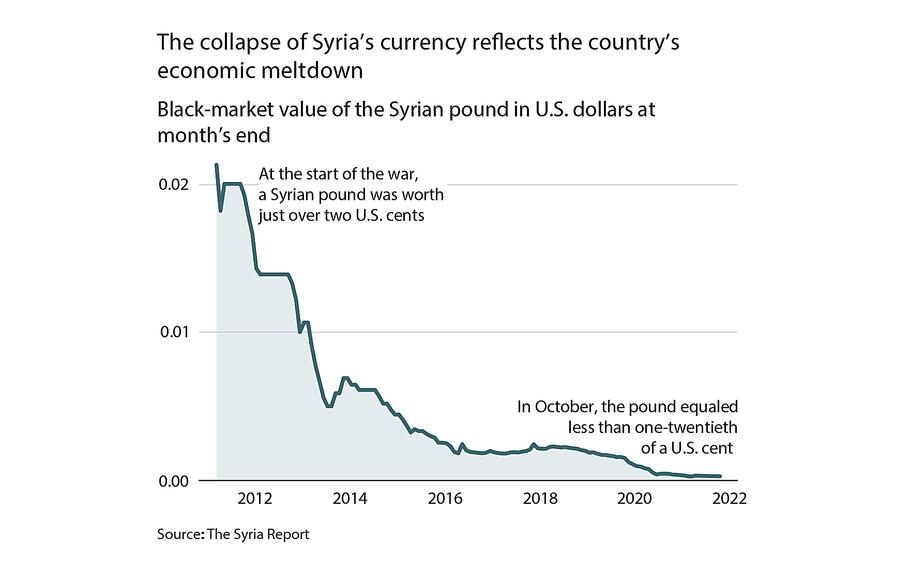

Against this backdrop, an endgame has begun to unfold. U.S. officials and Syria experts said that Assad has so effectively consolidated his control over the country's security apparatus and economy that he is poised to emerge from the war with a firmer grip on power than when it started. But after a decade of conflict, he is left in charge of a dismembered and decimated state where nearly half of Syria's territory is beyond his government's reach, entire towns lie in ruins and the currency has lost 85 percent of its value since the start of the war.

"In an era of a shrinking economic pie, the fight for resources becomes even more ferocious," said Robert Ford, who served as U.S. ambassador to Syria from 2011 to 2014. The climate of desperation "actually gives Assad even more leverage," Ford said, because so few potential rivals have the wherewithal, financial or otherwise, "to contest Assad's control."

Assad has portrayed the asset seizures as part of his promised fight against corruption. "There will not be any suspension to this process or leniency with any person involved because . . . ending [corruption] is an economic, social and patriotic necessity," he said at a ceremony in July marking his inauguration to a fourth seven-year presidential term.

And Ammar Waqqaf, a Britain-based Syrian businessman who supports the Syrian government, said that the targeted executives "are beneficiaries of privileges not open to the ordinary people. The state sees justice in getting them to pay more."

Start inner circle scroll

As Assad has struggled to retain power in Syria and his hunt for cash has grown more desperate, he has repeatedly shaken up his inner circle - even as the regime shakes down former loyalists.

At the center of power, the Assads have remained a constant. Bashar, 56, has ruled since 2000, when he assumed power following the death of his father.

Bashar's wife Asma, 46, is a British-born former banker who heads Syria's largest charitable organization. His brother, Maher, 53, is an army general who commands the elite 4th Armored Division, which was behind some of the most brutal campaigns against protesters and rebels.

Rami Makhlouf, 52, is Bashar's cousin and used his power to amass a fortune estimated to be worth billions of dollars. After a public falling-out with Bashar last year, Makhlouf was stripped of control of Syriatel, the country's largest cellphone service, and other companies in his empire.

Samer Foz, 48, is a businessman who built substantial wealth during the war, acquiring companies from others who fled the conflict and picking up prize real estate holdings, including the former Four Seasons Hotel. His standing seemed to wane after the United States imposed sanctions on him. Foz is rarely photographed.

Yasar Ibrahim, 38, has risen faster and higher than perhaps any other businessman. Virtually unknown before the war, he has emerged as Bashar's favored frontman over the past two years, displacing Makhlouf, outmaneuvering Foz and gaining control of the cellphone industry and other economic sectors. No photos are available of Ibrahim.

But the outcome adds to the bitter legacy of the Arab Spring, which had raised hopes of political reform across the Middle East and expanded economic opportunity. In Syria, the opposite has happened. Assad and his shrunken inner circle have found ways to cling to power and maintain aspects of their elite lifestyles, while much of the rest of the population faces a deepening humanitarian crisis.

More than 90 percent of Syrians now live in poverty, according to the United Nations. Many of the country's hospitals, schools and roads outside Damascus have been reduced to rubble. And drought has raised fears of famine, with humanitarian groups estimating that 12 million Syrians' access to adequate food is at risk.

The United Nations has estimated that rebuilding Syria will cost at least $250 billion. U.S. sanctions are already a major barrier to foreign investment, and the Biden administration has signaled they will remain in place until Assad agrees to substantial political reforms.

The treatment of MTN and others may further undermine the prospects of any money flowing into Syria. "No sane and rational foreign investor would think of doing anything in Syria under the current operating environment," said the executive who described the assault on MTN.

The mafia-like elements of Assad's strategy go beyond the seizures of companies.

The Syrian regime has also become an alleged drug trafficker, accused by U.S. and Western officials of producing mass quantities of the amphetamine Captagon at facilities in loyalist areas along Syria's coast. In 2020, European and Arab authorities seized shipments with an estimated street value of $3.4 billion - more than Syria's annual budget - according to the Center for Operational Analysis and Research, a global risk and development consultancy.

The regime is also accused of diverting tens of millions of dollars in humanitarian aid intended for impoverished Syrians.

A recent study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, for instance, documented how the Assad government has pocketed more than half of every dollar brought into the country by aid organizations - charging what CSIS said were artificially inflated exchange rates for Syrian pounds that aid groups need to buy supplies and operate. The Syrian central bank diverted at least $100 million between 2019 and 2020, CSIS concluded, by accepting dollars from aid groups and returning Syrian currency at a fraction of its worth on the open market.

Even before the war, Syria was widely perceived as a kleptocratic country in which the Assad family enriched itself by exploiting access to state-controlled assets and imposing parasitic partnerships on businesses.

But that approach has been upended dramatically over the past two years, as Assad turned on formerly trusted insiders and abandoned any pretense of entrepreneurial partnership.

Among the main targets has been the telecommunications industry, a singularly reliable source of revenue in a country where the poorest Syrians often carry cellphones even if they can't count on reliable access to electricity or clean water.

The regime began targeting companies on the periphery of the industry as early as 2018, according to Syrians with direct knowledge of the matter.

In one early case, a company that provided support services to the country's main cellular carriers was told that its clients would sever their contracts unless the smaller firm's owners relinquished control.

The company had more than 200 employees and revenue of several million dollars each year, according to a Syrian executive knowledgeable about the episode. Senior managers were encouraged to stay, and the business continued to operate largely as it had for years. But the company's contracts were taken over by a new entity, Al-Burj Investment Company, the executive said. Al-Burj was controlled by Ibrahim, a financier and businessman who has gained favor with Assad in recent years. Ibrahim's sister Nasreen was listed on corporate records as an Al-Burj executive, according to Syrian individuals familiar with the case.

"We were hoping to be one day be part of the new Syria - to be part of the reconstruction and that this regime would not be there," said an executive with knowledge of the takeover. "We no longer have any hope of going back." The executive spoke on the condition of anonymity and asked that the name of the company not be published, saying that relatives and employees still in Syria remain vulnerable.

The Assad regime soon shifted its attention to larger corporations that dominate the cellphone business.

MTN had entered the market in 2008 with the acquisition of a company that had been started by a Lebanese businessman, Najib Mikati, who is now Lebanon's prime minister. MTN invested heavily and came to hold roughly 45 percent of the Syrian cellphone market.

Then, in late 2019, the company was informed by Syria's main telecommunications regulatory agency that the 20-year license it had acquired just four years earlier would be canceled without an additional payment of $40 million. When MTN balked, regime pressure intensified, a second Syrian executive said.

In May of last year, the company executives were arrested. These five top employees, including four men and one woman, were detained in simultaneous 2 a.m. raids and taken to a prison run by the internal security branch of Syria's General Intelligence Directorate, according to Syrians familiar with the case. A sixth employee was taken into custody the next day from his office in Damascus.

The employees included MTN's senior managers in Syria, but not its chief executive, who had left the country earlier in the year. The arrested executives were interrogated for nearly three weeks and faced threats to themselves and their families before being released, Syrian individuals said.

"The main purpose was not to get information," one person familiar with the case said. "It was a message being sent."

MTN began negotiating to sell its 75 percent stake in its Syria operation to a company called TeleInvest that was controlled by Ibrahim, the Assad associate, who had previously acquired the other 25 percent from a Saudi investor.

But the deal with TeleInvest was delayed by concerns about Ibrahim's ability to secure the money for the transaction, an executive said, and then collapsed when the United States imposed sanctions on Ibrahim in mid-2020. The Treasury Department referred to Ibrahim as Assad's "henchman" and said that "using his networks across the Middle East and beyond, Ibrahim has cut corrupt deals that enrich Assad, while Syrians are dying from a lack of food and medicine."

MTN, which operates in 21 countries across Africa and the Middle East, worried that it might face U.S. financial penalties if it were caught doing business with the sanctioned Syrian, the executive said.

When the deal fell through, Assad's government moved to seize control of MTN through different tactics. In a lawsuit, Syria's regulatory agency accused MTN of violating the terms of its license, tax evasion and other charges, and secured a ruling that put the company under control of a court-appointed guardian.

The company disputed the allegations and challenged the ruling in court in Syria but lost that case. An MTN spokesman in South Africa said that the company "declines to comment any further on this issue."

The court then handed that role as guardian to TeleInvest, the same Ibrahim-controlled company that had tried and failed to negotiate a purchase of MTN.

The South African company surrendered, bowing out of a business that had generated nearly $1 billion in annual revenue before the war, though earnings had contracted significantly during the conflict. The company still had 6 million subscribers when chief executive Ralph Mupita declared in August that MTN would "abandon" its business in Syria after having "lost control of the operations through what we feel was an unjust action."

While still stalking MTN, Assad orchestrated a more audacious takedown within his own family.

Rami Makhlouf is the scion of an elite clan that Assad's father - Syria's longtime leader Hafez al-Assad - married into. With virtual free rein over the country's economy for nearly two decades, Makhlouf used his influence to build an empire reputed to be worth billions, though it was widely suspected that he was holding much of that wealth on behalf of his cousin, the president.

Makhlouf's most valuable asset was Syriatel, the dominant mobile phone carrier in the country, though he also held lucrative stakes in Syria's oil, banking and real estate sectors.

Makhlouf's exploitation of state power was so conspicuous that he was put under U.S. sanctions years before the civil war broke out, accused of having "manipulated the Syrian judicial system and used Syrian intelligence officials to intimidate his business rivals." The U.S. Treasury Department in 2008 called Makhlouf "one of the primary centers of corruption in Syria."

Last year, Assad began publicly denouncing his profligate cousin in terms similar to those used by the U.S. Treasury.

The attacks on Makhlouf came as Assad sought to deflect blame for a deepening crisis in Syria's already ravaged economy. A collapse in neighboring Lebanon's baking system left thousands of Syrians unable to access their savings and sent the country's currency into a tailspin.

Syrians also saw other reasons for Makhlouf's reckoning. His family's flaunting of its wealth - his sons have a habit of posing on Instagram with exotic cars - triggered outrage among impoverished Syrians.

There has also been speculation among Syrian expatriates that Assad's wife, Asma, who was born in London and worked as a banker with J.P. Morgan before their marriage in 2000, was asserting more control of the regime's finances to secure a fortune for the first family's three children.

The dismembering of Makhlouf's empire began in 2019, when Asma was put in charge of the assets of Al-Bustan Association, a Makhlouf-run charity that claimed to support families of regime loyalists killed in the war but became known as a conduit for funding for private militias. In 2017, the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on Al-Bustan for "recruiting and mobilizing individuals to support and augment Syrian military forces." The organization was at the center of "a vast private network of militias and security-linked institutions," the Treasury Department said.

Asma, who survived breast cancer in 2019, also heads the Syria Trust for Development, which serves as a major conduit for U.N. assistance money flowing into the country and as a key source of patronage for the Assad family, giving it a powerful say over who receives aid.

Several Syrian businessmen who fled the war said that Asma was behind the push to seize revenue from the cellphone industry in Syria and sideline Makhlouf, in part to ensure that her own eldest son, Hafez, is in a strong position to someday succeed his father.

Last year, Makhlouf suffered the biggest blow yet when he was stripped of his shares of Syriatel, one of the most profitable businesses in the country, with control of 55 percent of Syria's cellphone market.

A humiliated Makhlouf resorted to pleading for mercy from his cousin in a series of jarring videos posted on Facebook. He said Syriatel regularly turned over half its revenue to the state and could not pay more without facing collapse. He expressed disbelief that security agencies he once wielded against business rivals were now raiding his own companies. He pleaded with Assad to end his financial "suffering" and blamed a "cadre" close to the president for "framing me as the one who is wrong."

In his most recent video, in July, Makhlouf ranted against the new owners of Syriatel, accusing them of "thievery." He obliquely compared himself to Moses, suggesting that he would deliver Syria's poor from the predations of the "war profiteers" who had taken over his former company. Makhlouf did not respond to a request for further comment.

The videos marked a staggering fall for Makhlouf, while creating an unexpected opening in the position he had long held as Assad's money man.

Several ambitious Syrians auditioned for the job. Among them was Samer Foz, who had grown rich during the war by stockpiling properties including the former Four Seasons Hotel in Damascus, which has continued making money by catering to leaders of aid organizations and U.N. delegations that visit the country.

Foz had founded a holding company in the late 1980s that billed itself in online brochures as an "international group operating in a wide range of industries," from pharmaceutical supplies to a Lebanese television station. Foz has homes in Dubai and Latakia, Syria, according to the U.S. government, and is a Syrian national who also holds citizenship in Turkey and the Caribbean nation Saint Kitts and Nevis.

Syrians with knowledge of Foz's operations said he amassed much of his wealth by exploiting his network of connections and ingratiating himself with Assad during the Syrian conflict.

Foz used a private jet to crisscross the Persian Gulf region, soliciting funds for Assad from donors, according to Syrians familiar with his activities. He also delivered ultimatums to wealthy Syrians who had fled the conflict that they could either sell to him the companies they had left behind or risk losing everything.

Secret financial records unearthed as part of the Pandora Papers, which were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with The Washington Post, show that Foz used the offshore financial system to set up shell companies outside Syria during the war to hold a yacht, a jet and other assets. In 2017, documents show, Foz changed the name of one of his offshore companies from "Foz Holdings" to "Skyy Capital Limited," possibly to avoid attracting attention.

But his rising profile and involvement in a brazen real estate scheme put in him the crosshairs of the U.S. Treasury Department. He was the lead private investor in a real estate project called Marota City, which involved the planned construction of luxury high-rises in a Damascus suburb on expropriated land where the regime had bulldozed thousands of homes previously occupied by Syrians who fled the conflict.

The contract was valued at $312 million, according to the Treasury Department, and appeared aimed at attracting money from Persian Gulf investors. But the project foundered after Syrian backers faced a flurry of U.S. sanctions. Among them was Foz, whom the Treasury Department accused of having "leveraged the atrocities of the Syrian conflict into a profit-generating enterprise." Foz did not respond to a request for comment.

Foz has since been eclipsed by another Assad-backed upstart.

Yasar Ibrahim, a 38-year-old businessman who was virtually unknown before the war, has presided over the shakedowns of major Syrian firms from an office in Assad's presidential complex, according to Syrian executives and experts.

There are conflicting theories about what accounts for Ibrahim's rising influence. An expert on Syria's economy noted that Ibrahim's father had served as a consultant to Hafez al-Assad, and that the Ibrahim family is from the same minority Alawite sect as the ruling family. "He is Alawite, and they are loyal to Bashar, not Asma," who was raised Sunni, the expert said.

But others believe that Asma is Ibrahim's main patron, in part because of her reported close ties with two of Ibrahim's sisters. "He gained Assad's trust by that connection," said Joel Rayburn, who until last year served as special envoy for Syria at the State Department. "Little by little, he took on the moneyman duties."

Either way, Ibrahim now sits at the center of a remarkable constellation of companies in oil, food, construction and other sectors. One, Hokoul SAL Offshore, was hit with U.S. sanctions in 2019 and described by the Treasury Department as a "front company" for the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah.

Most importantly, Ibrahim has amassed near-monopoly power over Syria's cellphone market, having displaced the family owners of the support services company, pried control of Syriatel away from Assad's cousin and seized the reins of MTN after the company's capitulation in August.

The regime has portrayed these forays as a crackdown on corruption, a ploy that has won some public support, experts said. In that vein, Ibrahim has cast himself as a benefactor to targeted companies, even as he displaces their owners and commandeers their cash.

A Syrian executive said Ibrahim had summoned senior employees of the seized telecommunications support company to his office, trying to win their loyalties by saying he had intervened to rid the firm of corrupt bosses. He sought to convince the employees that he was "a good guy, a gentle guy, and a patriot," the executive said. In reality, the executive said, "Yasar is the bully," an enforcer for Assad.

Ibrahim did not respond to a request for comment made via the Syrian presidency, where he works as an economic and financial adviser.

Ibrahim and his sisters, Rana and Nasreen, were also put under U.S. sanctions last year for their allegedly predatory roles in the regime. The designations forced them to remove their names from the boards of directors of Syriatel and other companies. But their standing with Assad appears undiminished. Earlier this fall, Foz was forced to hand over his stake in the former Four Seasons hotel to Ibrahim, according to Syrians with knowledge of the matter.

"The Ibrahims are by far the rising stars - it's boggling how far their influence is spreading," said Karam Shaar, a consultant on Syria and research director at the Operations and Policy Center in Turkey. Even so, Shaar said Ibrahim's standing is as precarious as that of any of his predecessors. The Assads "use people like him as pawns, as fronts for the regime," Shaar said. "If you get too strong, you will be chopped and replaced by someone else."

Syria today faces a "humanitarian catastrophe [that] is now among the largest in the world," according to a senior U.S. official. The vast majority of the population lives on less than $1.90 a day and 6.2 million are listed as "internally displaced" by the United Nations, meaning they remain in Syria but were forced from their homes by a conflict in which Assad used poison gas and barrel bombs against his own people.

In recent months, there have been growing signs that other Middle East leaders who once worked toward Assad's ouster are resigned to his survival. But U.S. officials and Syria experts said the prospects for postwar recovery in Syria remain distant. The Biden administration has cautioned countries across the Middle East not to aid Assad financially or otherwise. And while Russia and Iran helped rescue Assad militarily when he seemed most at risk of losing the war, neither country has signaled any willingness to cover the projected cost of Syria's rebuilding.

Meanwhile, life for ordinary Syrians continues to deteriorate. Soaring prices put all but the most basic foods beyond the reach of ordinary people. In Damascus, lines for fuel stretch for blocks on end from the early morning hours till late at night, residents say. Blackouts are common.

"We have deadly poverty, high prices, people cannot pay their rent," said Salwa, a Damascus resident who asked that her full name not be used. "Everyone wants to leave, she said. "People would give anything to leave the country."

The shakedowns have padded regime accounts, with the Finance Ministry claiming that government revenue had tripled during the first nine months of this year. But Assad may be undermining the country's longer-term prospects, said Shaar, the consultant. "He thinks you can coerce businessmen to do what he wants, but that's not how economies work," he said. "They will run away."

The country has indeed seen an exodus of business owners - possibly thousands of them, according to Syrian media reports. Many are taking what remains of their capital and expertise to Egypt and other Arab countries.

Assad, however, remains ensconced in an upscale neighborhood of Damascus, a city largely unscathed by the conflict. Elites who have profited from the war continue to dine out and drink in bars and restaurants.

Even the Makhloufs appear to be clinging to aspects of their privileged lifestyle. Rami Makhlouf continues to live at his villa in a suburb of the city. His son, Ali, surfaced on social media in October in Beverly Hills behind the wheel of a $300,000 Ferrari.

- - -

The Washington Post's Suzan Haidamous contributed to this report.