Middle East

Afghan free media was touted by the US as a success story. Its journalists are now under threat.

Stars and Stripes August 4, 2021

Afghan journalist Zainullah Stanikzai keeps photos on his phone of Aliyas Dayee, his friend and a fellow reporter, who was killed Nov. 12, 2020 in southern Helmand province when a bomb attached to his car detonated. Stanikzai said on Aug. 2, 2021 that he hopes to come to America through a program to allow those who worked for U.S. media companies and are under threat to receive a visa. (J.P. Lawrence

Stars and Stripes)

KABUL, Afghanistan — Hoshang Hashimi escaped his hometown of Herat on the same day the Taliban captured two other journalists.

He left quietly, saying goodbye only to his mother and father, and packing two small bags with his professional camera equipment and other essentials.

Hashimi said that because he had worked for international media outlets like The Associated Press and Agence France-Presse, he would be in danger if the Taliban took the city.

So on Monday, he flew to the relative safety of Kabul on one of the last planes out of Herat before mortar rounds struck the city’s airport, suspending all flights.

Like dozens of other Afghan journalists from across the country, Hashimi is now in the capital taking refuge from Taliban offensives after the withdrawal of most U.S. and coalition troops.

Hoshang Hashimi, an Afghan photographer, left his home in Herat, Afghanistan on Aug. 2, 2021, after a Taliban offensive encircled the city. Hashimi is one of about 90 reporters who have fled rising violence throughout the country for the capital city of Kabul. (Hoshang Hashimi)

The 34-year-old is part of a generation of journalists who began their careers partly as a result of American nation-building efforts over the past two decades.

But Afghanistan’s free press, long seen as a notable success story and the most independent in the region, is under threat from Taliban violence, journalists and activists told Stars and Stripes.

“We will lose a lot of our freedoms if things keep going as they are,” said Najib Sharifi, the president of the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee, and a longtime contributor to NPR and other news organizations.

Some 136 cases of violence against journalists were recorded in the first half of the year, the Kabul-based committee said.

The Taliban has forced about 90 journalists to flee to Kabul, the group said. More than 300 journalists have left the profession since the beginning of the year.

Taliban violence and economic pressures caused by decreasing foreign aid threaten press freedom in Afghanistan, Sharifi said.

He also mentioned increased repression by the Afghan government, which arrested four reporters in the southern province of Kandahar recently.

The U.S. has invested millions to support Afghan media, believing that strong, independent journalism would support the growth of democracy and promotion of human rights.

Tolo TV, one of Afghanistan’s most popular television channels, began after a $220,000 grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

But while Afghanistan ranks highly in press freedom compared with nearby countries, it remains one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists, with over a dozen media workers killed since last fall.

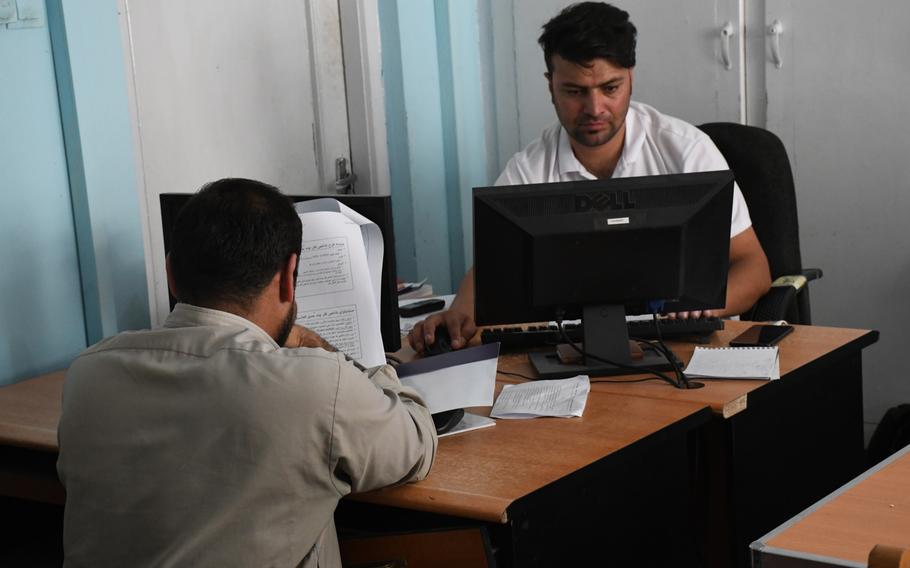

Journalists work in the newsroom of Pajhwok news agency on Sept. 4, 2019. Many Afghan reporters from across the country have taken refuge in Kabul from Taliban offensives following the withdrawal of most U.S. and coalition troops. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Among them was Indian photojournalist Danish Siddiqui, who worked for Reuters and was killed while embedded with Afghan forces in southern Kandahar province last month.

In April, Human Rights Watch accused the Taliban of intimidating and killing journalists as part of a wave of assassinations that also targeted judges, lawyers and activists.

The militant group has denied involvement in the killings, which remain unclaimed, and it has since said it would not target Afghans who worked for U.S. news organizations once international forces leave. But many media professionals said they don’t believe the Taliban.

The militant group took over the FM radio station Radio Nawbahar in the northern province of Balkh this summer. The head of the station, Nabi Hamdard, told Stars and Stripes that music is now banned.

“They only broadcast about religious issues, Taliban (poetry), verses of the Quran,” said Hamdard, who like most of the station’s employees fled when the militants took over.

Some journalists say they are getting threatening messages on social media that they believe come from pro-Taliban accounts, with stock images and made-up names that translate to “Watcher Watcher” and “Fix Yourself.”

Last fall, Taliban fighters called Zainullah Stanikzai, a reporter in the southern city of Lashkar Gah, and demanded that he tell them how many reporters there were working for foreign media.

Stanikzai, whose friend and fellow reporter Aliyas Dayee had just been killed in a car bomb attack, knew he had to flee to Kabul.

After working for Reuters for nine years, Stanikzai hopes to come to the United States on a visa program recently announced by the State Department to help those who worked for U.S. news organizations.

The new “Priority 2” category of the U.S. Refugee Admission Program will apply to Afghans and members of their immediate family who may be in peril.

Stanikzai, 40, said he never wanted to leave his home country. But the violence of the past year as U.S. and allied troops left changed his mind.

“It was very fearful for me,” he said. “We’re not people who have armored cars; we’re journalists.”

Sharifi, the president of the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee, has mixed feelings whenever he sees Afghan media professionals leave the country.

He said he knows the dangers they face, but he hopes the media can persevere.

“If we lose all our journalists, that will be a big loss for Afghanistan,” Sharifi said. “I want to stay. I want to fight. Who’s going to save this country if everyone leaves?”